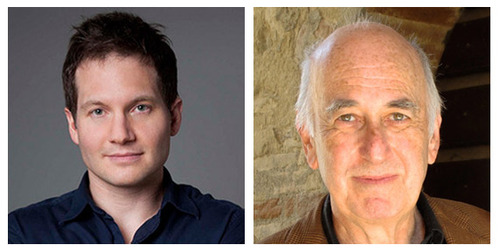

John D’Agata and Phillip Lopate

During 2014, Essay Press will release a series of chapbooks investigating what creative nonfiction can learn from small-press publishing communities in poetry. One of these chapbooks, curated by David Lazar, will consist of three dialogues by editors of prominent nonfiction anthologies. Each dialogue will examine the potential to reshape a literary field through an experimental form of anthologizing. The Conversant has published an audio preview of one of these dialogues, conducted by John D’Agata and Phillip Lopate, the directors of the nonfiction programs at the University of Iowa and University of Columbia, respectively. We’ve transcribed a segment of the conversation below.

JOHN D’AGATA: There’s an interesting question you have to ask yourself when you’re doing an anthology, and that is how important it is to present new work from well-known writers rather than those old chestnuts that had originally made them famous. When I was doing my second anthology, The Lost Origins of the Essay, I found myself treading ground that you [Phillip Lopate] had already well-traveled. For example, I knew that I wanted to include Sei Shonagon, because she speaks so wonderfully to the argument that that book is trying to make. And the same thing with [Yoshida] Kenko, Natlia Ginzburg.

PHILLIP LOPATE: And Montaigne.

JD: And Montaigne, from whom I selected the same essay as you had—and even same translation. For some I was able to find different translations, as with Sei Shonagon, or commission new translations, which I did for a few of the selections I included. But in other instances you face a dilemma: those old chestnuts might be speaking directly to the argument you want to make, and yet because they’ve been so frequently anthologized you could end up looking like you aren’t imaginative or well-read enough to find alternatives.

PL: I really feel you have to put the chestnuts in even if they’re obvious, though. For instance, in Writing New York, we [had the same issue with] Melville’s story “Bartleby the Scrivener.” I thought it was one of the five greatest stories written about New York City. And I said, “It’s gotta go in.” But they [the editors] said, “It’s in every anthology in the world.” And in the end, it went in. I just thought, you know, come on. It’s obvious, but sometimes things are obvious for a reason, because they really are… they’re peaks, they’re mountains. So, we put that in and we put in “Crossing the Brooklyn Ferry” by Whitman because, you know, it’s too great. We put some of Whitman’s journalism in, but you can’t always buck the obvious. And one...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in