On Genesis Breyer P-Orridge’s Solo Exhibition S/he Is Her/e

I’m generally perplexed when famous musicians, trained or not as visual artists, express an avid need for art world approval, showing work that appears dated or flimsy in relation to their musical practice. There’s something disjunctive and contrived about such bids for legitimacy, especially given the fact that everyone knows the art world will do anything to exploit fame for money à la Jay-Z’s now notorious performance/video, Picasso Baby, which had everyone a-twitter last summer.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge (BPO), who has achieved more of a cult status than fame, is a vivid exception to this tendency, her art and music having evolved coextensively since the beginning of her career. And as her recent survey at The Warhol Museum brilliantly conveys, the objects she’s produced have always served a larger function, emerging out of ritual and performance-based actions that are deeply visionary in nature.

Take Blood Bunny (1997-2007), a life-sized rabbit carved from wood found in Mexico, rubbed with both the blood of the artist and her other half, Lady Jaye, who “dropped her body”—as BPO describes her passing—in 2007. Attached to the strange talismanic object is Lady Jaye’s pony tail, the entire work radiating sacrificial energy under a glass bell jar. The blood, purchased on a trip with Timothy Wylie (founder of The Process Church of the Final Judgment) comes from the residue of ketamine injections taken for astral travel in 300 consecutive “trips”, a number determined by Wylie to best retrieve and harness the knowledge gained during what he calls “glimpses into the miraculous.” When I ask about this work, Gen shows me a series of scars on her arm that represent cuts made by Jaye to bring her back into her body.

Breyer P-Orridge, Blood Bunny – Ketameaner Kat, 1998 – 2011, Talismanic Pandrogeny Object: wood, blood (Lady Jaye), blood (Genesis), hair (Lady Jaye), cloth, adhesive, bell jar, 13 x 6.5 x 6.5 inches, Courtesy INVISIBLE-EXPORTS

Similarly, Alchymical Wedding (1997-2012) consists of three hand-blown glass globes laterally hung in a steel frame, each full of the hair, nails, and skin of the two artists, suggesting an ongoing powerful engagement with ritual magic. Influenced in the mid-70s by writings about Western magic, namely those of Aleister Crowley and Austin Osman Spare, BPO saw in ritual the possibility of making things happen, whereby magic became a form of cutting up behavior.

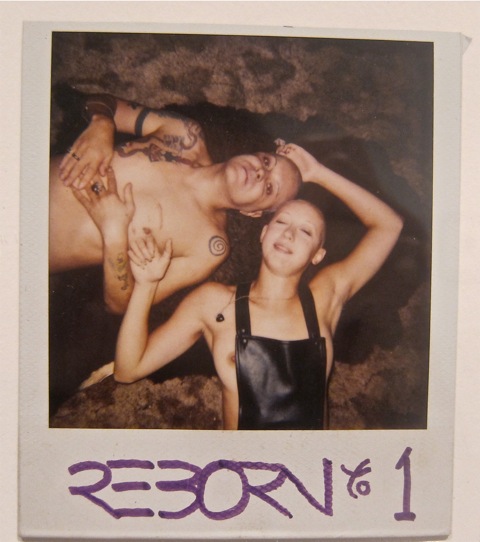

Both Blood Bunny and Alchymical Wedding span the period of Pandrogyny, the remarkably prescient project in which the couple began undergoing various plastic surgeries to resemble one another, seeking to dissolve boundaries between self and other in an ultimate manifestation of true love. To this day, P-Orridge still refers to herself as “we” (adopting the feminine singular, as I do here, when the plural becomes confusing).

Breyer P-Orridge, Alchymical Wedding, 2012, Hot-rolled steel frame, hand-blown glass, cork, hair, nails, skin, 14 x 36 x 14 inches. Courtesy INVISIBLE-EXPORTS

Vividly expressed in books like Thee Psychick Bible, a compilation of writings by the artist from 1981-1991, this trafficking in love and magic is at the heart of BPO’s work, though she also – significantly – describes herself as a “cultural engineer”. The latter term refers to her efforts to blur not just the line between self and other, but male and female, spirit and matter, art and life, and pain and pleasure, binaries, she insists, that hold the human species back from its true potential. “The body is not a finished project,” she tells me, “we are already at this point where if I want horns, fur, or gills to live underwater, it is increasingly possible, I reject this idea that we are stuck with the bodies we get.”

While some in the art world scoff at, or hold in suspicion, such metaphysical aims, others are profoundly drawn to it. After a lecture given in conjunction with her Warhol survey, for example, the artist found herself talking to Madison, a nine-year old girl who by way of introducing herself declared “I’ve been a fan of your work all my life, and I’ve seen your show twice already!” At dinner after, Gen and I decided that the girl had to be an old soul to be so free in her thinking, musings that were without irony. Yet if I shared this discussion with fellow art critics, most would find it laughable, hippy nonsense because the spiritual in contemporary art remains highly suspect, regarded as unfashionably eccentric, or just plain naive.

“You have to be careful, wisdom is dangerous.”

The artist as shaman does have its precedence, of course, best exemplified in the charismatic work of Joseph Beuys, the postwar artist whose extravagant claims that he was shot down as a German fighter pilot in WWII (and healed by a nomadic clan in the Simean desert) formed the raison d’etre of his entire oeuvre. P-Orridge’s own mythobiography—filtered through the Third Mind concept of William Burroughs and Brion Gysin (major influences as well as friends), and the cosmic prism of psychedelia (Gen lived with Tim Leary for a time)—finds its origins in the vision-induced founding of COUM Transmissions (1969), a Fluxus-based performance collective.

COUM not only combined street action, collage, and performance, but represented P-Orridge’s forays into the malleability of language, words and symbols alike. S/he is Here offered a rare glimpse into this pivotal moment with four black-and-white photographs from Anti-Fashion (1977), a series I’d never seen before, that depict a young (still male-identified) P-Orridge in suspenders and black trousers. Performing before a mirror, head and face bound in saran-wrap, one arm tied behind the back, the reflective, multiplying images of “self” expressed in these experiments with sadomasochistic play, also eerily foretell a pandrogyne future: “There are more than one of you,” S/he writes in Prayers for Sacred Hearts, a poetic mission statement accompanying the show. “Maybe hundreds to choose from.”

Breyer P-Orridge, COUM Anti-fashion 1, 1975, Vintage black and white photograph, printed by Genesis P-Orridge, Signed on recto: Genesis P-Orridge, 1977, Stamped on verso: Coum Transmissions, Anti-Fashion, September 1977, Coum Personnel: Genesis P-Orrige, Photographer: Cosey Fanni Tutti, 10 x 8 inch, Courtesy INVISIBLE-EXPORTS

As has been widely accounted in profiles on the artist, COUM culminated in The Prostitution Show (1976) at London’s ICA, which incorporated the use of transvestite guards, bloody tampons, rusty syringes, etc. Also well known is the outcome of this incendiary show, the British government’s official branding of P-Orridge, and performance partner Cosi Fanni Tutti, “wreckers of civilization”. Emblazoned in the tabloids, the accusation became a badge of honor, though few would ever know its impetus: a British law prohibiting self-harm, defined as the “breaking of skin”, which BPO vehemently protested as a violation of the right to control one’s body.

Breyer P-Orridge, COUM Transmissons, The British Government, 1975, six wooden boxes, adhesive, plastic, glass, taxidermied mice, vintage handprinted black-and-white photographs 8 x 12 x 6 inches, Courtesy of Amy Gold and Brett Gorvy

Soon joined by Chris Carter and the late Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson, COUM evolved into Throbbing Gristle (1975-81), who are widely seen as pioneers of electronic/industrial music. The technocult group, whose improvised performances and dark ambient noise would continue to involve graphic visuals and a cut-up style utilizing home-made electronic instruments, intense frequencies, and found sampled tape sounds, also found notoriety before fame. Their attempts to deliver “entertainment through pain” (a concept attributed to Gen) via a host of outre subjects – serial killers, sadomasochism, Christian fascism, etc. – deliberately sought to provoke listeners out of their complacency.

This desire to disorient and decondition normative thinking reflects another ongoing theme in BPO’s work. When one looks at the art made during the TG years, the role of the occult in attaining these goals reemerges once more. Altered postcards with cheeky sexual commentary and collaged images of the artist in drag yielded to more mystical meditations on the erotic.

By 1981, BPO had formed a new band, Psychic TV, along with “TOPY (Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth), another music-cult hybrid project – still extant, its worth noting – replete with mission statement and logo, “thee Psychick Cross”. The latter greeted viewers at the Warhol survey like a beacon to the future, its fluorescent glow signifying one was entering another domain, one beyond the mere physical.

Breyer P-Orridge/ Daniel Albrigo, Thee Ghost,2010, neon, 30 x 40 inches, S/HE is HER/E, 2013, Courtesy Andy Warhol Museum.

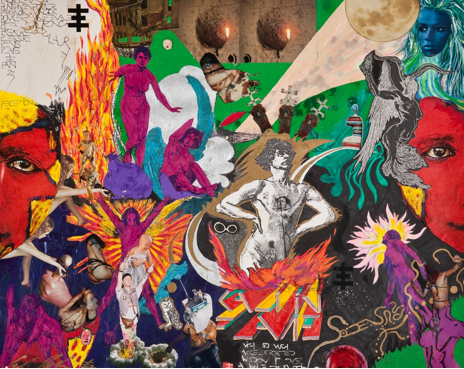

When I wrote about the works known as Sigils, after they were first exhibited in New York, P-Orridge described them to me as, “surrendering to something so deeply that there is no separation between the desire and your ability to manifest it,” alluding again to the dissolution of material boundaries. Taking the form of cut-ups in which “personal effects” – belongings, self-portraits, body fluids, dream symbols, etc. – were bound together through ritual incantation (as much as glue), their intricate hallucinatory forms and cacophonic colors put to rest any question that P-Orridge was a “real” artist capable of aesthetic complexity. That the Sigils, as with most of P-Orridge’s work, are ongoing (in the Warhol show, they span a period from 1985-2001) reminds us both of their functional nature, and the artist’s conviction in art as transmogrification.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Kali in Flames, 1986. Mixed media, 20 x 25 inches, Courtesy INVISIBLE-EXPORTS

“You can make friends with random chance.”

It is ironic that when I first met Gen I was barely aware of BPO’s illustrious musical career, inviting her and Jaye to participate in an exhibition I curated, Keeping Up with the Joneses, with examples from their Pandrogyne project. This was in 2007, six weeks before Jaye’s untimely passing, the “cheap suitcase” that she called her physical body suddenly opening and falling away. The shock and grief that came in the wake of this leaving was staggering, and Gen’s capacity to move on despite her anguish, moved me greatly. It still does. Since then I have written about her work in art historical terms, talked to her about intimate subjects like aging and sexiness, and discussed the prospects of starting an artist commune via a trailer-park model (my vision), always inspired by her willingness to be vulnerable and open, not to mention her boundless generosity.

My music friends, naturally, couldn’t comprehend my ignorance, her legendary contributions to music, her cult status in that world, being well-established. After I began in earnest to listen to PsychicTV and TG records, I couldn’t fathom it either. How had this immensely gifted, truly visionary entity with a vast output of work from writing and music to visual art and filmmaking, largely passed me by? The real question being: why wasn’t her work better known? The answer, I think, resides in a sentiment I overheard one Warhol museum guard express to another: “The work is so disturbing, but when you hear her talk, her message is so positive and uplifting, spiritual in a way.”

Clearly, the art world has an easier time accepting the transgender aspects of Gen’s utopian vision, while its darker side – the bloodletting and occult activities, namely— are still circumscribed by fear. This may sound odd considering the opus of body-based performance work that has dominated post-1960s art, but every time I screen Orlan’s documentary, Carnal Art (2011), for my art history students, and watch as they writhe in disgust as the camera zooms in on her flesh being cut into and rearranged, I’m acutely aware of how persistent sacrosanct notions of the body are. I use the saint analogy, central to Orlan’s own thesis, to try and pry open these fears, but it is slow-going. The ugly flesh and blood realities of existence, whether reduced to abject sensations, or elevated to transmogrifying aims, are just too visceral and disturbing for most to embrace.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Orlan or Not, 2009, Mixed media, 14 x 11 inches, Courtesy INVISIBLE-EXPORTS

Post-minimal sculptures, conceptual drawings, and painterly pursuits seem a lot easier to digest, especially by artist-musicians. Which brings me full circle. It is precisely the resistance to what is easily consumed that forms the core of BPO’s vision: “There is so much possibility we don’t realize we have access to or even that we have the right to access. So, to us, the artist is a signifier of the ability to short-circuit all those filters of social control we inherit, long enough for a new vision to come through.” Spoken by a 21st century shaman, if ever there was one. Now all we have to do is listen.

Psychic TV (PTV3), 2013, performing at The New Hazlett Theater as part of S/HE IS HER/E, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge retrospective at The Warhol Museum, photo courtesy of author.

Jane Harris is a Brooklyn-based writer whose writings have appeared in publications from Art in America and Artforum to Time Out New York, and the Village Voice. She has also contributed essays to various catalogues and monographs such as Hatje Cantz’s Examples to Follow: Expeditions in Aesthetics and Sustainability (2010); Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art Carla Gannis (2008); Phaidon’s Vitamin P: New Perspectives in Painting (2004) and Vitamin D: New Perspectives in Drawing (2005), Universe-Rizzoli’s Curve: The Female Nude Now (2004), and Twin Palms’ Anthony Goicolea (2003). She is currently at work on the book After: The Role of The Copy in Modern Art. Ms. Harris is a member of the art history faculty at School of Visual Arts, and also curates (a recent exhibition, Crazy Lady, 2011, received positive reviews in Time Out New York and Huffpost). She is the founder of the blog(zine), janestown.net, and a sample of her fiction can be read at www.ducts.org/content/picklocks/).