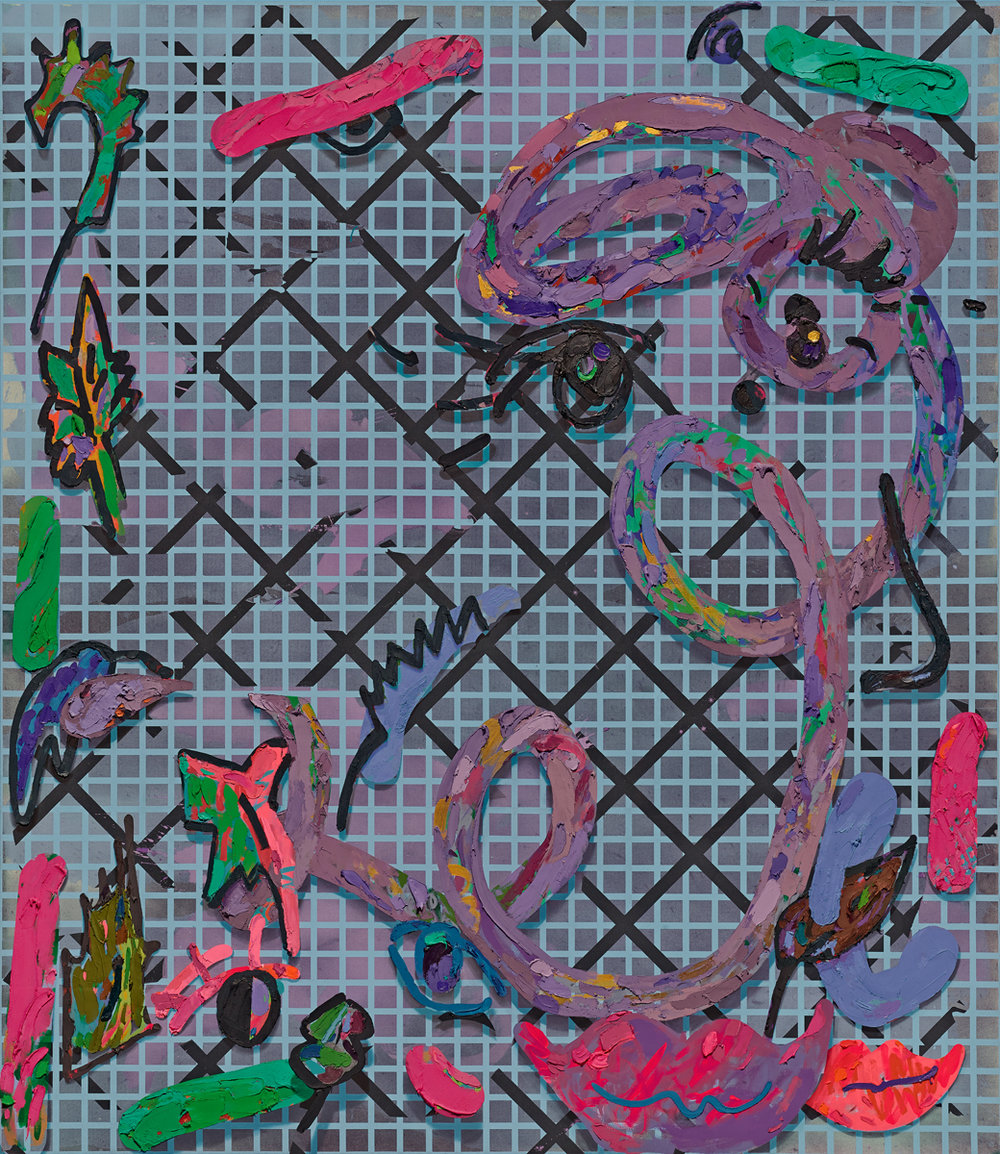

(Untitled, 2013, Oil, acrylic, and Flashe on canvas, 137.5 x 120")

THE BELIEVER: Can you talk about technique? I heard once that you told a class that at a certain point you figured out that most of the time, if a painting wasn’t working out, its problems could be worked out technically—in other words, that problems and solutions are both most likely technical, and not questions of content, or underlying concept.

LAURA OWENS: In art school, they teach you to struggle through the process: If you have your image down, you’ve painted it, and it’s not looking the way you wanted it to, you can do wet on wet—you just keep moving the image around, like the way de Kooning worked. You just keep painting over and over and over. For me, at some point, the idea of struggling through the process was not as interesting as doing tests and executing the painting after I figured out all of its elements and how they were going to work together. I have a really pragmatic approach to making the paintings—it’s a process of doing lots of tests on small canvases, trying out different materials, or rearranging things until what I have coalesces with my original intention of how I wanted it to look. And a lot of times the first three or four tries will be just terrible, but they won’t be the actual object—just the preliminary sketches—so I keep going until I get it right.

BLVR: So once you’ve come to your conception of the painting you stick to it and just try to find a way to realize that conception. You don’t discard it and try to find something else, or modify it depending on where your process takes you.

LO: Right. It’s really different than just diving in, which is how a lot of painters work. They throw something on the canvas, respond, throw something else on the canvas, respond, or they have a preconceived way of working that has to do with the materials and the steps you go through with the materials until you’re finished with a painting. I don’t use either of those methods; some people have commented that it’s more of an old-fashioned way of working, through sketches and studies, maybe like the way fresco painters used preliminary cartoons. I get to a point with the sketches and tests where I know about three-quarters of what the painting will look like, and then I make it. At that point, I’ll look at it and ask, “What else needs to happen?” Which is a sort of no man’s land where you can either go too far or do too little and you have to carefully gauge where to stop.

BLVR: I read that Rousseau’s imagery came from picture books, since he never actually visited the jungle.

LO: Yeah, I read that too.

BLVR: And Alex Katz once replied, when asked whether his landscape paintings derived from nature or from art, that they came unquestionably from art. The nature imagery in your work clearly references a wide range of art history—eighteenth-century embroidery, Chinese and Japanese landscape painting, Rousseau, obviously. But I also get the feeling that, unlike Katz, some of the references and meanings in your depictions of nature are more internal, more personal.

LO: So do you think it doesn’t look like it comes from other art? Or just not completely.

BLVR: It definitely is coming from other art, but when I read the Katz quote I took it to mean that even if in Katz’s own retinal experience he sees things and those things get translated into a landscape painting, for him, symbolically, the work’s meaning lies in its reference to art, and not to his natural environment or anything to do with its intrinsic qualities and meanings. By comparison, I sense that your depictions of nature transcend your relationship to art history and convey something more personal as well.

LO: Oh, I hope they do. Each particular painting has a sort of grab bag of places it’s coming from, and those get kind of mixed and chopped up and moved around, and among those elements can be just something that happened on a hike or it can be a painting I saw in a museum or a drawing I made. There’s no limit as to what the work is referencing. It could be an unknown artist… frequently, I’ll see something in an artist’s work that is really a minor, minor part of the artwork—like a shadow on someone’s face from a hat, and I’ll think, “Oh my God that’s the best thing!” And I’ll turn that one element into a painting. Instead of looking at the art, the totality of the artwork, and taking that in and using it, I’ll take little pieces, and I think of that as a more personal and interpretive quality that’s coming from within. I’m not sure a lot of other people would walk up to the same artwork and see the shadow on the person’s face from the hat and be like “Do you see that!” It’s about noticing things that interest you, and that definitely happens with the natural world as well. Looking at relationships between different things in the natural world and what it is that interests me about them. But the work is definitely not meant to depict the natural world.

BLVR: It isn’t?

LO: Well, when I think about depicting the natural world I think of, say, botanical drawings, and all of my paintings are sort of shorthands—notations, if even that. A lot of the animals I put in the paintings, it’s very hard to say which animal they are—a badger or a squirrel or something in-between. In terms of the rendering, it’s not accurate or anything, especially compared with people who went out into nature researching botany—there’s a whole history to that that I think of as painting that depicts nature.

BLVR: There is a doodley, lavender and rose pink canvas in the Moca show with these Miróesque lines. The signature on that painting is on the upper left corner, upside down. I’m wondering: Was including a joke about the subjectivity of orientation a way of mediating the so-called grandeur, or grandiosity, of a big, abstract painting?

LO: I didn’t intend to put the signature on it when I was making it; it happened later. I knew I wanted to do something with this space pen I had, so I drew all over the canvas with it, and then I stained it in places, but it didn’t feel finished somehow. I was at that place where the canvas was mostly done but I had to kind of go with the flow of figuring out what was next, and how much more to do. I had this all-over pattern, referencing Miró and textile design. It had a nice spatial quality with a lot of the canvas showing, but I felt like it wasn’t finished. There needed to be a figure, and a figure-ground relationship. At some point I just thought, Okay I’m going to simply sign it with this tube of paint, and then right after I did it, it occurred to me to have it upside-down. The humor for me is how far above your head the signature is—it’s dislocated from the sign of the artist in such a distinct way that it could almost be a self-portrait of a sort. I think what you said about the joke on orientation was something that I responded to after the fact. But in terms of thinking that I needed to take away from the grandeur of the painting, I feel no shame about having paintings be as grandiose and ridiculous as possible.

Read Rachel Kushner’s full interview with Laura Owens from May 2003, and check out Laura Owens interviewing Rachel Kushner, ten years later.