A rather important warning is given far too late in Rodrigo Fresán’s tenth novel, Kensington Gardens. After we’ve already finished the dizzying, drugged-up saga, in which the curlicue fantasies of J. M. Barrie’s Edwardian London meet their historical doppelgänger, the lysergic ’60s, after the author has nearly finished his acknowledgments, he breezily mentions, in a footnote, his hope that we didn’t put too much stock in his narrator. Some of his story might have been fabricated, some even hallucinated. “Who knows,” Fresán shrugs. That’s something we should have figured out, sure, but the tardy tip still feels a bit cruel.

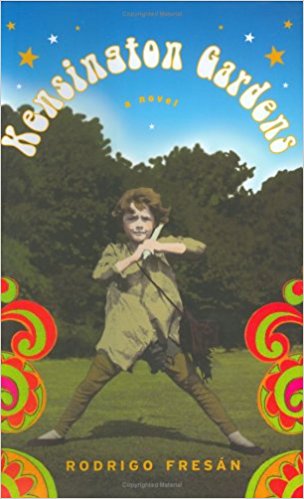

Kensington Gardens, the Argentine novelist’s first book to be translated into English, is both a biography—occasionally true, often fictionalized, at times fantasized even within its own conjured truth—of Peter Pan scribe J. M. Barrie, and a personal history of its own narrator, modern-day children’s book author Peter Hook. Hook, an orphan of wealthy, acid-addled flower parents, created the Pan-like Jim Yang, a character played in film adaptations by the child actor Keiko Kai, who also plays the audience for Hook’s self-fable; Hook has kidnapped the youth, and the novel is a ream of apostrophes in his direction.

Of course, we readers are the ones actually playing Kai, which points both to the daunting power of our storyteller and to the novel’s wild arithmetic of substitution and mutability. In Gardens’s dense opening sequence, Hook describes Peter Pan’s suicide—the sextegenarian Peter Llewelyn Davies, Barrie’s inspiration for Pan, jumps in front of a speeding Tube train at the moment of Hook’s “increasingly hypothetical” birth—and wonders if it’s possible that he’s Pan incarnate. Such are the shifty foundations of Hook’s story: It’s a sort of quicksilver reality, in which identities and names, fact and fiction, sleeping and waking, can always dress up as each other. Hook’s book is about Neverland, and resembles Neverland, and sometimes even takes place in “Neverland,” his rococo childhood mansion, where Bob Dylan once vomited on his lead soldiers.

All this makes Kensington Gardens an extremely, exquisitely confusing book. But its metaphysical riddles aren’t gratuitous. As the stars of Barrie’s kids’ lit bleed into Hook’s life and the cultural record, books and lives find themselves drawing from the same textual field. That’s a comment on the fictional feel of ’60s excess: a world of real actors with posh names—Sebastian Compton-Lowe, Alexandra Swinton-Menzies—too twisty to be true.

Like the Barrie he describes, Hook reads his own life in acts and scenes, complete with stage directions; he compulsively interrupts descriptions of days in his life with quotes from the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life.” But while Gardens gives its narrator a long leash in his quasi-Baudrillardian dismissal of the “real,” it won’t let him get away with it. When a Hollywood starlet calls cocaine “fairy dust,” fantasy shows a sinister tinge. And in the novel’s tragic final scene, Hook’s narrative relativism falls apart. Earlier, in one of his prettiest lines about Barrie, he had suggested that the author “opens books like windows, opens books to let the light of a story into this gloomy life.” That was a convincing image, but in the end it’s also an excuse. This is a children’s story, with many youngsters about, and leaving a window open is a quick way to exit the fiction.