The modern history of Sudan is rife with civil war, dating back to the country’s achieving independence in 1956. Sudan’s current conflict has been ongoing since 1983, and pits the agrarian tribes (Dinka, Nuer) of the southern portion of the country, who are largely Christian and animist, against the Islamic fundamentalist central government, based in the northern city of Khartoum. The primary entity fighting for the south is the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army.

In the first installment of “It Was Just Boys Walking,” Dominic Arou, a Sudanese refugee now living in Atlanta, was on a plane from Kenya to southern Sudan, in hopes of finding the family he left when he was somewhere between six and eight years old. In the second installment, Dominic recounted the days, in the early part of the current Sudanese civil war, when he was forced to leave his village in Marial Bai, and subsequently walked with thousands of other boys, a good portion of them orphaned, hundreds of miles through parched lands. Many hundreds died along the way, of hunger, disease, and animal attacks, en route to refuge in Ethiopia. Together these boys became known as the Lost Boys. After spending four years at a UN-sponsored camp in Ethiopia, regime change drove out the Lost Boys by force, and they then walked back through southeastern Sudan and finally to Kenya, where they stayed for the next eight years at the refugee camp christened for them at Kakuma. In this installment, we join Dominic again on the journey to his village, riding in the cargo hold—along with the author, the author’s brother, and many tons of humanitarian aid—of an aging plane helmed by three Russian pilots. If Dominic makes it back to his village, he will be the first Lost Boy living in America to return home.

*

After a few hours in the air, we have to stop in Nuba and unload the supplies with which we share the cargo hold. The plane has been flying low over the semi-arid lands, trees and paths visible the entire flight, and now the plane descends close enough to see the villagers running to the runway as we land. The airstrip is paved with ochre-colored dirt and is cracked and uneven, making the landing eventful, if not harrowing.

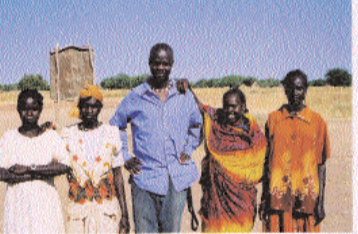

Dominic gets out, down a five-step ladder, as do the plane’s four other passengers. We descend onto a rocky airstrip amid a dry and mountainous area, dusty and dotted with scrub. There is no airport; there are no buildings, outside of an ancient-seeming fort about five hundred yards away. There are about thirty Sudanese villagers standing on the edge of the airstrip, and for a second, no one seems...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in