It was on a cold evening in March 2017, during my first visit to Srinagar, Kashmir, as a reporter, that I first read an excerpt from Cups of nun chai in Kashmir Reader, one of the region’s primary newspapers. I was sharing a room with my friend’s little sister, twelve-year-old Asma, and we read the testimonial slowly, tracing the words with our fingers, as I became aware of the realities children in Kashmir have to live with, the violence enmeshed in their everyday lives. Cups of nun chai is an ongoing work by Australian artist Alana Hunt, who lives on Miriwoong country, in Western Australia. In Hunt’s own words, all her work, in both Australia and Kashmir, engages with “the violence that results from the fragility of nations, and the aspirations and failures of colonial dreams.” Cups of nun chai, meanwhile, “is at once a search for meaning in the face of something so brutal it appears absurd” and “an absurd gesture when meaning itself becomes too much to bear.”

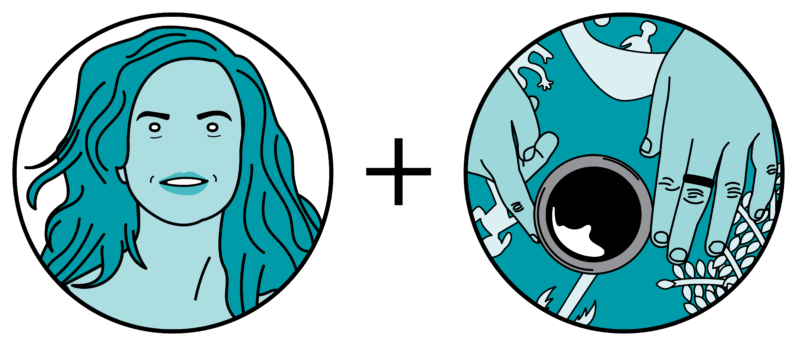

The book version of Cups of nun chai is a collection of 118 conversations that Hunt held with people over a cup of nun chai, or salty Kashmiri tea. A memorial to the more than 118 Kashmiri civilians killed by the Indian armed forces in 2010, Hunt’s book, published in 2020, questions the normalcy of the violence established by the Indian nation-state’s military occupation of the Kashmir valley and the media landscape that erases and obfuscates the loss of Kashmiri lives.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in