I first saw Nick Lowe in 1979 when his band Rockpile opened up for Blondie at the Sunrise Musical Theatre in Sunrise, Florida, about a ten-minute drive from my childhood home in suburban Fort Lauderdale. Until that time, I think the only concerts I’d been to were Boston and Styx, so this was a bit of a turning point in my life as a music fan.

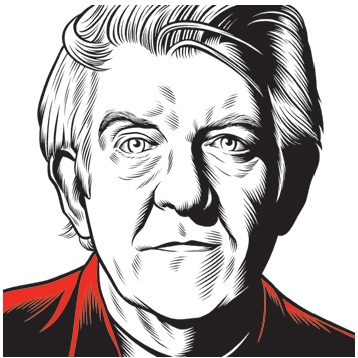

Since then I’ve seen Nick many times, either as a solo act or with a band. In 1987, I drove many hours to Atlanta to see him open for Elvis Costello, whose first six albums were produced by Lowe. After that show, I waited by the stage door to meet him and Elvis, and watched as he signed autographs and joked with fans. So when the Believer asked me to interview someone, Lowe came to mind. I was a fan, but not a seasoned journalist, so I wanted to talk to someone who was talented and friendly.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in