The Homeless Simulator is a roughly six-foot-high box of semitransparent plastic. It looks like a high-design porta-potty, with a low, horizontal hatch on the front to lift and crawl through rather than a vertical door. The prospect of entering is daunting, and not just because of the cramped space. The audio tour warns: “Please be advised that riding the simulator is not recommended for people with bipolar disorder or poverty-related depression.” Inside, there’s nothing but a vintage cake mixer with maybe forty cents’ worth of pennies in the mixer’s bowl. “To truly experience homeless simulation,” instructs the tour narrator, “swiftly turn the switch of the mixer onto speed ten and leave it on for at least ten seconds or up to twenty-four hours.”

The Homeless Simulator, “where the dream of making lots of dough is turned into a nightmare,” sits in the middle of the Homeless Museum, also known as HoMu BKLYN, in the main hall next to the café, en route to the curatorial department, and not far from the gift shop. Gray and white plaques mark the nearby high gallery, staff and security room, education department, and the membership office, located behind a closed door in the café. The museum does not keep regular hours, so visiting means dropping by on one of the open-house days, which occur at unpredictable intervals and are advertised mostly by word of mouth. On these occasions, HoMu’s director of development, Madame Butterfly, greets visitors dressed in a traditional kimono and wooden sandals. Her hospitality is graceful and genuine, even if she is the first sure sign that HoMu is not your average straight-faced arts organization. One look at the list of fellow board members posted near the entrance (Madame Tussaud, creative director; Robobum III, treasurer; and Florence Coyote, director of public relations) and Madame Butterfly suddenly seems less anomalous. After taking visitors’ coats, she equips them with portable CD players loaded with the audio tour.

Madame Butterfly’s buoyant voice narrates a history of the pieces surrounding the simulator in HoMu’s main collection: Birth of a New Museum, a somewhat graphic and literal depiction of the title, painted by museum director Filip Noterdaeme in his fledgling graduate school days; MoMA HMLSS; a series of miniature reproductions of works of art in the Museum of Modern Art, including Meret Oppenheim’s famous fur cup, Object, and Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel safely encased under Plexiglas after returning from a traveling exhibition; and a small model titled Captive Audience, a suggestion for other galleries and museums to line their floors with a powerful adhesive commonly used for trapping rodents in order to keep their visitors glued.

The next stop is Café Broodthaers, named in honor of Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers. Cuisine inspired by his work with empty egg- and mussel shells is the main fare. One can observe, through the skylight above the dining table, the museum’s emblematic weather vane, “able to capture the most subtle vibrations outside the museum, enabling HoMu to react instantaneously to changes in the world’s cultural climate.” Until very recently, Café Broodthaers served only one thing: a single, cured Edward Island mussel with a hardboiled egg. To drink, chilled organic whole milk. A small dish of artisanal sea salt is set down next to the plate, along with a delicate, two-pronged fork. The air of refinement makes chasing cold seafood with a swish of whole milk seem like an underappreciated delicacy. HoMu brings back to the plate the meaty insides Broodthaers left out of his work, and when the innuendo of the egg, milk, and femme-form-mollusk combination hits, it makes the meal all the more lively. The newest addition to the café menu is a dessert: Haacke’n-Daz, a surprisingly tasty honey-mustard ice cream effigy of the German artist Hans Haacke.

The Archives and Meteorology Department holds all of HoMu’s cultural-climactic studies. A map purportedly based on measurements taken by the weather vane details the motion of cold fronts in art (Futurism) and warm movements (Expressionism), and highlights from some of HoMu’s public events are on display. Articles from the Village Voice and the New York Times recount the director’s Penniless at the Modern project, a “civic action” staged on the reopening of the Museum of Modern Art in November 2004. The director paid the admission price, which increased 67 percent to $20 a person—the highest in the city—in rolls of pennies, twelve and a half pounds of them, to be precise, to underscore the burden such a fee would be to potential art enthusiasts. Letters to Glenn Lowry of MoMA and Guggenheim director Thomas Krens, honorary HoMu trustee, discuss possible collaborations and alliances as like-minded colleagues in the business of high culture.

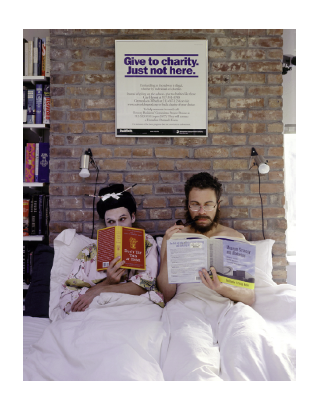

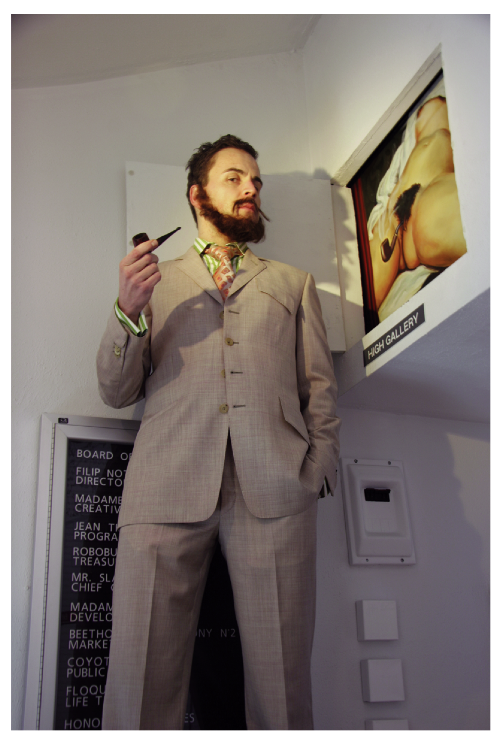

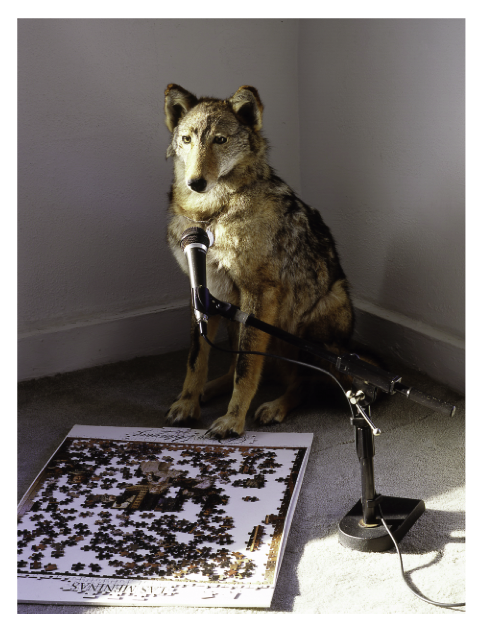

“At HoMu, we are proud to offer our visitors a glimpse behind the scenes to explore the inner dynamics of a cultural institution,” the tour announces as guests arrive at the Staff and Security Room. “This is truly the inner sanctum of the museum… where Director Noterdaeme does his most important work.” Depending on the day and the type of work being done, any number of situations have been known to arise behind this closed door. Visitors are instructed to knock three times, and the door opens to a bright, airy room with a bed, a closed-circuit camera feeding the scene onto a computer screen, and Florence Coyote, a taxidermied coyote who is HoMu’s PR director, in the corner behind a microphone, studying a thousand-piece puzzle. She usually has something to say, and delivers a howl as anyone approaches. (Close listening reveals cryptic wisdom like “There is nobody walking away clean in this world any longer.”) Sometimes Director Noterdaeme is asleep in bed, fingers still wrapped loosely around his signature pipe. A subway sign bearing the slogan “Give to Charity, Just Not Here” hangs above him. Other days, he is sitting up, mustache waxed into upright points, puffing his bubble-blowing pipe, and engaging visitors in an open forum discussion. He is prepared to meet the public with cue cards close at hand, printed with phrases like “I dwell in possibility” (Emily Dickinson) or “No one should be generous, everyone should be altruistic” (Lawrence Weiner). This is his platform, and the director is a force to be reckoned with. He pontificates about everything from eating dark chocolate to information overload to the disintegration of the avant-garde. The experience is like a hybrid of a sit-in and a vaudeville performance. Recently, the director’s catchphrase was “I am at the peak of my decline,” spoken on a day when HoMu BKLYN launched its first addition to the original museum: the Chicken Wing.

*

HoMu BKLYN’s main hall is actually the entry foyer of a two-bedroom apartment on the top floor of a brownstone in Brooklyn Heights, inhabited by Belgian artist and HoMu founder Filip Noterdaeme, and his partner, Daniel Isengart, a.k.a. Madame Butterfly. The museum café is their kitchen; the curatorial department, “an intimate space for serious business,” is the bathroom, tastefully equipped with a slide projector to flip through images of art masterpieces while doing said business. Staff and Security is their bedroom. The education department is a TV monitor fit seamlessly in the now-defunct fireplace, playing a loop of Noterdaeme’s video work. The membership office is behind the closed door of their freezer. Every inch of the apartment has been transformed—unbeknownst to the landlord—into the most recent incarnation of the Homeless Museum, which has existed in one vagabond form or another since 2002.

“It’s difficult to pinpoint a beginning,” Filip says, then lapses into a circuitous explanation, as he’s prone to do—with or without the beard and pipe he dons when playing the role of HoMu’s director. In these playful digressions, it is clear that words are as familiar a medium to him as painting, sculpture, or performance. He is skillful at making sincerity feel fragile; though he never appears to be lying outright, the truth is cut with just enough wryness to suggest that what he says may be as much fantasy as fact. A boyish face and gentle manner heighten this effect and belie his true age. Until he recalls hearing Joseph Beuys lecture and references living in New York in the 1980s, he could easily pass as being in his mid-twenties. Occasionally, Filip’s banter falters while he looks for a word in English. The break is a surprise, since the most obvious traces of his origin have been nearly erased by twenty years in New York.

Maybe it is hard to place how all of this began because now, a year after HoMu found its temporary shelter in Daniel and Filip’s home, the museum shapes their lives as much as they shape it. The museum is not disassembled between open houses. The pieces of the collection are fixtures in their everyday life, and have, in some cases, even changed the way they talk about things. A trip to the bathroom usually involves “curating some business.” Getting a book means consulting “Archives and Methodologies.” The phrase in the bathroom, “Homeless in mirror are closer than they appear,” has gained a resonance that they didn’t expect, Filip says. A plastic ball hanging from the ceiling showcases a pair of faux-diamond-encrusted high heels as it turns, and Filip continues to wind his way through a string of loosely threaded events: a class he once taught at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he witnessed a leak near the painting Washington Crossing the Delaware; his amusement with the frantic rescue effort that ensued; a recent leak at HoMu that inspired him to collect the water in a carafe for a piece he calls Liquid Gold, an “anonymous donation” to the museum’s collection. Then he deadpans: “Some things just spring out of nothing.”

What is latent in the story of the leaks is ultimately a central HoMu refrain: the spontaneous event that disrupts more calcified establishments is an opportunity at HoMu for transformation. In 2002, HoMu began with only a website storefront. Under an image of a sharp-dressed man towing a stack of colored milk crates on a derelict New York street, is the declaration: “A product of New York City’s cultural decline, HoMu is a budget-and-staff-free, unaccredited arts organization that enables and engages cultural dialogue practiced at the intersection of the arts and homelessness.” HoMu began with all the trappings of a legitimate operation—a logo and brand identity, a catchy acronym, a board of directors, a collection, a mission statement—in order to provide resistance against just such organizations. It looked the part without actually existing. Ceci n’est pas un musée, as Magritte might have said; the museum that you see is not what you think it is, and to understand it requires looking a little closer.

The inaugural public event came in 2003 with the unveiling of the $0.00 Collection, an assembly of found objects color-coordinated with major works of art by masters such as Caravaggio and Cézanne. As the name suggests, the $0.00 Collection resists being bought or sold, and, befitting a homeless exhibition, HoMu squatted in a temporarily vacant residential space to show it. Gabrielle Giattino, an independent curator, saw the collection and was taken by Filip’s sense for crafting paradox and gift for triple entendres. She decided to include him in a show later that year called Quixotic, held in a furniture store on Crosby Street. Filip’s installation The Homeless Simulator for Golf Players and Their Peers was an early and less forgiving version of the one currently at HoMu BKLYN. It was a game of putt-putt for two people, set up in the store’s window, and the loser was banished to the simulator, which in this case meant taking off some article of clothing and begging for a dollar in change in order to get it back.

Filip and Gabrielle continued to collaborate, including a project for the Armory Show in the spring of 2005. By then, HoMu BKLYN had taken shape, and the mission statement, as printed this time in a brochure, had evolved to target “the corporate growth of cultural institutions.” The brochure also included a note from the director:

I too wondered if I could not become homeless. For some time, I had been no good at anything. I am nearly forty years old… Eventually the idea of giving up everything crossed my mind. But instead of becoming a street beggar and rely solely on donations for survival, I decided to become a museum director and turn my home into a museum. But your home does not look like a museum, my friends said. It will, I said, and named it the Homeless Museum.

HoMu set up an advice booth for museum directors and curators at the fair and offered a chauffeured trip to Brooklyn for the first HoMu open house. Space was limited to twenty-five people, and it filled within hours of announcing the project. Yet on the actual day, not one person showed. The list was a veritable who’s-who of art collectors and art advisors, and is now on view as HoMu “personae non grata” in Archives and Methodologies.

Birth of a New Museum, the first stop on the museum audio tour, proposes an alternate, equally salient backstory. The painting is a take on Gustave Courbet’s 1866 work L’Origine du Monde, or The Origin of the World, which hangs in the Musée d’Orsay. For those unfamiliar with Courbet’s painting, it is a full-frame rendering of a woman’s vagina (some art historians speculate that the model was American painter James McNeill Whistler’s lover Joanna Hiffernan). Filip’s version adds a pipe to the painting, right where it counts, and adjoins a second canvas that is a depiction of his own torso. The more graphic of the two halves on display is one of the only surviving remnants of Filip’s time at Hunter College, and was what prompted his premature dismissal on the grounds of plagiarism.

For his graduate work, Filip devised a fictitious character to play, a certain Marcellus Wasbending-Ttum, “Homoplagiarist,” who in description bears a striking resemblance to HoMu’s director. Marcellus wore a fake beard, smoked a pipe, brought a lapdog with him to group critiques, and in general taunted the rules. Marcellus’s charge was to act like a curator, presenting a collection of work in different contexts. Some of the work he presented was done by Filip, some was not; one of those pieces was the painting in question. Meanwhile, Filip blindfolded himself and sniffed other students’ paintings to judge their quality during critiques, and made classmates come to look at his work in the rancid cement bathrooms of their underfunded public school. His persona was a parody of the bespectacled New York intellectual, who undoubtedly had a presence on the faculty. Given Filip’s clear intention of using an invented character to question authenticity in a work of art, the likelihood that plagiarism was the real reason for his expulsion seems low. As Daniel puts it, “Filip undermined the authority of the school, and they had to find a reason to get him out of there.”

The HoMu audio tour is forthcoming about this history, giving an honest if distilled version, along with a clever, full-circle connection: “More than ten years before the inception of the Homeless Museum, this painting had already exposed everything Noterdaeme set out to do as an artist, which he pursues today as a museum director: to draw back the curtains from the naked truth about cultural institutions.” What it does not elaborate on is that after leaving Hunter, Filip began a long period of working as an arts educator, but not necessarily producing as an artist. For nearly fifteen years, he was immersed in the museum world, first as a teacher in a program for children at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and eventually as a lecturer at the Guggenheim. Filip was witness to a particular era in the Guggenheim’s history; in the 1990s, under the direction of Krens, the museum mounted its campaign for global expansion. With new branches designed by big-name architects planned in cities all over the world, it aspired to become the first international museum franchise. Krens has since risked bankrupting the foundation and has been ridiculed for diluting the museum’s programming, but at the time, the disparity created by the overblown high culture of art began to resonate. The provocateur in Filip found a new subject worthy of critique.

For Filip, using the edifice that typically preserves all that is precious—the museum—as a framework to start a real conversation about how we relate to poverty in a culture of affluence and how museums shape taste, was the perfect paradox. His ability to pair contradictions in this way is one of the qualities that puts him into dialogue with the surrealist and conceptual artists he honors as influences in the HoMu collection. Broodthaers worked mostly as a poet until he began a career as a visual artist late in his life; on the occasion of his first exhibition he famously stated, “I, too, wondered if I couldn’t sell something and succeed in life.” Among many other things, he went on to start a museum in his home as an act of hermetic defiance. Beuys, whose 1974 performance I Like America and America Likes Me inspired the creation of Florence Coyote, used his multifaceted concept of social sculpture as a means to free access to art from the confines of a gallery or museum, and to make art something practiced not just by those designated as artists.

Filip is the first to recognize that the Homeless Museum’s name can be a difficult hurdle. Some dismiss the project before they ever visit as profiteering at the expense of the already downtrodden, though Daniel is confident that people who make the journey never leave with any misunderstanding. A number of works in the collection directly involve New York’s homeless, and the Patron Circle in the Membership program requires making a $150 donation directly to a homeless person at the member’s discretion, but HoMu has no pretense of being about social work or homage in the traditional sense. On its most basic level, HoMu engages visitors in the experience of looking at art by placing it in a context so intimate there’s no choice but to participate, so absurdly unpretentious that no one is intimidated. The “valuelessness” of the work at HoMu combats what Filip recently described as “the degradation of art through commerce.” If social work takes place, it’s through identifying elements of our immediate surroundings that are conveniently overlooked, and finding a way to bring them into the conversation. Though it risks being didactic, the hope is that by extension, visitors will be receptive to a broader range of possibilities even beyond the world of art.

“HoMu is not an antimuseum, but more of a deviant museum,” Filip says. “The language of art and the infrastructure of museums can always present things in a different light. They can transform our perceptions of reality, for better or for worse. I am simply mimicking that process.” How long the Homeless Museum will remain in its current location before moving on is unclear, but there seems to be no shortage of material that is fair game for satire even while it remains in Brooklyn. In September, HoMu instituted a new entrance policy, “Pay What You Weigh,” and Director Noterdaeme is hard at work on a new HoMu offshoot, a response to what he identifies as “museum obesity” in the trend of star-architect-designed museum expansions: ISM, or the Incredible Shrinking Museum.