In 1895 the German Jewish art historian and banking heir Aby Warburg started World War I. It wasn’t until an October evening twenty-three years later that he revealed this to his family. At gunpoint.

Later that same evening in 1918, Warburg was taken away by men in white coats. After brief stays in sanatoriums in his native Hamburg and in Jena, he took up residence at an exclusive clinic outside Kreuzlingen named Bellevue. He was not the clinic’s first or only celebrated visitor. The deeply strange French writer Raymond Roussel, beloved of the surrealists, sojourned there, as would Vaslav Nijinsky, the German Expressionist painter Ludwig Kirchner, and pioneer feminist Bertha Pappenheim (better known today as Freud’s “Anna O.”).

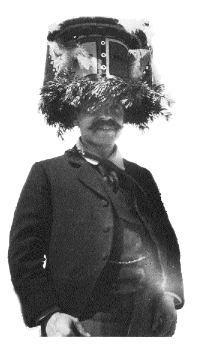

Unlike some of Bellevue’s patients, Warburg was not un malade imaginaire. He was totally mad. Convinced that the cooking staff was serving him the flesh of his own family, he became a vegetarian. His schizophrenia was reflected not only in the fears that plagued his mealtimes but also in the rhythm of his daily life. Though lucid and sociable in the afternoon and evening, he began each day in a wildly primal state. As a rule, his mornings were filled with bouts of energetic roaring. Warburg’s doctor encouraged visitors to come see him, though he carefully specified that afternoons were best. A colleague of Warburg’s arrived one day shortly before noon. Entering the elegantly appointed Bellevue, he heard the distant echoes of a wild kingdom. Half an hour later, Warburg greeted him, impeccably attired and as refined and cordial as ever. After a few minutes he took his guest aside and with an air of great amusement confided, “My dear friend, did you hear all that roaring? Well, you would never guess. But that was me!” Warburg then smiled brightly and the two men embarked on a lively discussion of fifteenth-century Florentine art.

Shortly after the celebrated art historian’s admittance to Bellevue, Sigmund Freud wrote to the clinic’s director to ask after Warburg’s future. Ludwig Binswanger, whose uncle had treated Nietzsche and who was not unfamiliar with the difficulties of creative genius, replied that Warburg was severely manic-depressive and likely to remain that way. (In the published correspondence between Freud and Binswanger, “Prof. V from I” is an alphabetical encrypting of “Prof. W[arburg] from H[amburg].”) Binswanger noted with chagrin that although Warburg had come to Bellevue to undergo “the talking cure,” he remained singularly uncommunicative—with people. He did, however, speak with what he called his Seelentierchen, his “tiny soulful animals”: the butterflies and moths that were the frequent companions of his lonely hours. Binswanger first had a real glimpse of what, in fact, was secretly troubling...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in