A Thomasson, according to Japanese conceptual artist Genpei Akasegawa’s inaugural stab at defining it, sometime around 1982, is “a defunct and useless object attached to someone’s property and aesthetically maintained.” A doorknob in the middle of a wall, for instance, or the reinforced guardrails of a two-meter footbridge leading directly to a dead-end dirt road, or a stairway with a recently repaired banister that connects to a second-story window. It is something discovered in the urban landscape, generally, that serves no discernible structural or cultural purpose and whose continued existence can thus be understood only, in the context of modern capitalist logic, as art.

Understood is a heavily freighted word to use just there, but consider who was doing the understanding at the time: Akasegawa, an avant-gardist gadabout and writer with a penchant for pseudonyms, plus a bevy of his art students and eventually a small delegation of readers of his column in the photography magazine Shashin Jidai. They roved around Tokyo finding, inventorying, and commentating Thomassons with a curiosity that reads as perfectly genuine, if not quite serious; the cleanest distillation of the spirit in which they conducted their inquiries may in fact be the etymology of the word Thomasson, after an American baseball player who, during his tenure with the Yomiuri Giants, struck out so often he earned the nickname “the giant human fan.” “He had a fully formed body,” Akasegawa muses by way of explanation, “and yet served no purpose to the world.”

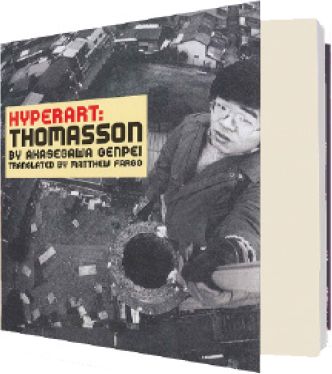

Hyperart: Thomasson is, and doesn’t purport to be much more than, a collection of Akasegawa’s columns, followed to what is presumably their actual historical termini. (It is also, for the record, a book filled with black-and-white images that are surpassingly lovely in themselves, equal parts psychogeographical whimsy and Richterian spectrality; while we’re at it, translator Matthew Fargo’s afterword alone is worth the cover price.) Shashin Jidai was more of a Playboy than an Aperture, and Akasegawa, avowedly eager to avoid highfalutin discourse, devotes much initial throat-clearing to distinguishing art, which is created by an artist, from hyperart, which is created by a combination of circumstances—entropy, desuetude, the “cruel pace” of the modern world—and merely recognized by an observer in the right place at the right time. He does not, however, deign to say that hyperart is easy to make, or, rather, to find; the would-be discoverer is...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in