Fletcher Hanks, nicknamed “Christy” after Baseball Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson, was, by all accounts, a louse. An alcoholic and a wife-beater, Hanks once kicked his four-year-old son, Fletcher Jr., down a flight of stairs. The punt and subsequent tumble left the boy unable to speak intelligibly for five years. “My old man didn’t like runts,” explained the younger Fletcher. The boy was runty, to be sure, and suffered from rickets, but his dad’s rage was something beyond reckoning. “My father,” he said, “was the most no-good drunken bum you can find.”

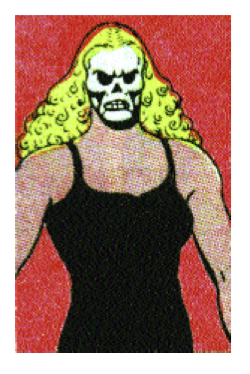

When Hanks wasn’t pummeling his wife or abusing his young son, he wrote and drew superhero comic-book stories. Hanks completed a few dozen of them between 1939 and 1941, the dawn of what is now considered the genre’s golden age. There are few remaining copies because the characters didn’t catch on with readers, and Hanks, as an artist, didn’t catch on with collectors. Among his creations were Stardust, an interplanetary crime fighter, and Fantomah, a white jungle-protectress.

This month, Fantagraphics publishes I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets! The Comics of Fletcher Hanks. Edited by cartoonist Paul Karasik, who discovered the artist in the early ’80s while he was an associate editor at Art Spiegelman’s comics review Raw, the fifteen-story collection boasts visual wonders freakish and rare. There are a rabid mandrill and a furry Venusian, asphyxiated magazine editors and giant bipedal rats. Bombings, gassings, and islands turned waterside down are all part of the Hanks landscape. Most peculiar of all, however, is that, contrary to every rule of the genre, the stories are almost completely devoid of fights.

Most traditional superhero comics follow a predictable format: The villain does something villainous. Hero and villain fight. The villain is captured, or beaten into submission, or is accidentally killed. Within this tripartite structure, the pre-conflict setup and post-conflict comeuppance serve largely as bookends to the fight scenes, which make up the narrative meat. In the tales of Fletcher Hanks, however, there are hardly any fights at all—few, certainly, of any consequence or duration. Instead, there are extended setups during which the villain commits a variety of horrific acts. After a speedy capture (often without a blow thrown) the reader is treated to panel after panel of the villain being tortured, humiliated, and tossed about.

Here is one story: Stardust, “the most remarkable man who ever lived,” discovers a plot to steal all the gold from Fort Knox. The evil Slant-Eye (despite his title, he is not of Asian descent) plans to use the gold to establish a “modern pirate stronghold” on a South Seas island. He and his henchmen drop gas bombs on...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in