1.

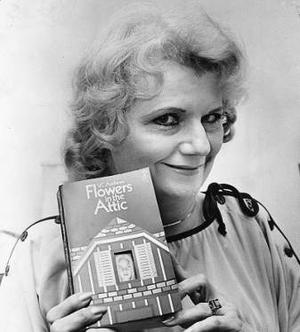

This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of the publication of V. C. Andrews’s Flowers in the Attic, the best-selling novel about incest, imprisoned children, and very, very bad parenting. Andrews went on to write six more books, each one beloved by millions of readers, mostly young women, and each a play on the same themes that made Flowers wonderful and unique: lust, violence, and pain. For two generations now, a private ritual of female adolescence has been reading Andrews’s spine-creased paper-backs, often passed down from an older, wiser girl with the whispered promise of secret knowledge hidden between the covers.

But despite her popularity, almost nothing has been published on Andrews. While gallons of ink have been spilled over genre novelists Philip K. Dick and Jim Thompson, the sum total of book-length Andrewsiana consists of one guide for the library market, one bibliographic checklist, and one mass-market trivia book. It’s hard to imagine another writer in the same peculiar position.

You could argue that Andrews’s books are so unusual and original that critics, scholars, and other “serious” readers don’t know what to do with them. Though there’s an obvious debt to the Brontë sisters, nineteenth-century sensation novels like Lady Audley’s Secret, and Daphne du Maurier’s Gothic fiction, at heart Andrews’s novels have little in common with the genres where they ought to fit. They’re too offbeat for romance, too slow to qualify as thrillers, too explicit for Gothic, and far too dark and complex for young adult. Many booksellers shelve them with horror, but Andrews’s concerns with family, emotion, and relationships put her books firmly outside the genre. Although the supernatural makes brief appearances in Andrews’s work, her largest topic is the all-too-natural tragedy of families gone wrong.

Ultimately, Andrews’s novels constitute their own genre, in which secrets, lies, desire, and moral corruption all stem from—and are contained in—the family. In her world, parents starve their children, sister and brother become husband and wife, and grandparents punish grandchildren for being “devil’s spawn.” No one is to be trusted, and few adults are who they claim to be. Most significantly, there are no happy endings. For all their teen-girl fantasy elements, the books are also gritty, raw, and extremely dirty. There is little cynical or formulaic about them. If anything, they are too raw, too revealing of the author’s own obsessions–which, as we’ll see, might be exactly why no one ever talks about them.

On the rare occasions when reviewers have been compelled, presumably by cruel editors, to write about the books, they concur: V. C. Andrews isn’t just bad, she is beneath contempt. “Flowers… is deranged swill,” a Washington Post reviewer opined in 1979. In a 1982 New York Times “Fiction in Brief” column that includes reviews of potboilers like Danielle Steel’s Crossings and Shirley Conran’s Lace, the most venomous is reserved for My Sweet Audrina, Andrews’s strangest book and her only stand-alone.

The reviewer claims she’s unable even to follow the story line, then asserts that she not only doesn’t understand the book, she doesn’t want to. “The story begins when the second Audrina, the narrator, is about 7 but since she isn’t allowed to go to school and is regularly told she has no memory, who knows?” she writes. “Who cares is another question.… Damian and Ellsbeth become lovers again. Ellsbeth dies. Does a sensible reader really want to know more?”

More recently, in 2001, Zoe Williams, writing in the Guardian, dismisses Andrews’s writing as stunted ramblings that read as if “done by computer, with a built-in Teetering On The Brink Of Womanhood template.”

The passage of thirty years, and the devotion of millions of young women, hasn’t helped Andrews’s reception at all (although, to be fair, the devotion of millions of young women has rarely helped any artist’s reputation much). In the first glow of Flowers’s success, when Andrews was at least mentioned in industry news reports, she was often cited in the same breath as up-and-coming horror writer Stephen King. But while King has gone on to respectability and full-page reviews in the New York Times, V. C. Andrews is still the same shunned “trash” novelist. And while horror, mystery, and science fiction have earned some respectability from a blurred high/low division in pop culture, Andrews’s books are pretty much just where the Times reviewer left them in 1982. The sensible reader does not want to know more.

If we were less sensible, and did want to know more, what would we see? Maybe that Andrews picked up on something that was swirling around her, a dark side of the 1970s we still haven’t looked at very clearly and whose shadows still cling to us. Maybe we would discover that her books actually contain a taloned commentary on the Freudian family romance, the process by which children escape their parents’ erotic hold by fantasizing that they are the abandoned offspring of a noble family (or, in the case of Flowers, the cast-aside product of an incestuous marriage). Certainly we find in Andrews’s books a more disturbing look at the secret lives of girls. In a 2004 article in this magazine, Amy Benfer writes of the gauzy pleasures of the Sweet Valley High novels, their pastel covers offering “the most satisfying form of pornography I had.” When we look at Andrews, however, we see an astoundingly sinister view of girls’ sexuality that yokes punishment and desire. Both Sweet Valley High and Flowers feature twins prominently—and it is hard not to see a dark joke in the name Andrews gives her twins, Dollanganger, as if they are the dark doppelgängers of every teen twin-tale to come before, or after. But while the Sweet Valley High books reassure teen readers with creamy covers and tales of malls and school rivalries, the Flowersseries offers up a saga of sin, terror, and revenge, the dark covers featuring a keyhole, beckoning us in. In reckoning with our pleasure in her books, then, we must examine our own drive to see our darkest desires and shame writ large again and again. We might even have to revisit our own personal tales of abuse, and our feeble attempts to lock trauma up and throw away the key. Most of all, if we weren’t so sensible, we would see a full flowering of adolescent-girl rage.

2.

V. C. Andrews’s books were an instant success, beginning with the publication of Flowers, in 1979. While most famous for her first series, Andrews also completed one stand-alone novel, My Sweet Audrina (1982), and the first two books of a series about the trials of the intertwined Casteel and Tatterton families. (After Andrews’s death—around the time of the second book of the Casteel series—books continued to be written under the V. C. Andrews name by ghostwriter Andrew Neiderman.)

At the center of Flowers is the Dollanganger family, a beautiful, middle-class suburban clan whose blissful life is shattered when the beloved father is killed in a car accident. Our narrator, teenage Cathy, along with her three siblings—beloved older brother Chris and a pair of younger twins, Cory and Carrie—accepts her mother’s word that the only way they can survive is if she can win back the love of her wealthy father, who rejected her when she married. The family moves to the estranged father’s ancestral estate, Foxworth Hall. The four children bunk in the attic while their mother attempts to reestablish her relationship with her father. At first the attic, which is spruced up with bedrooms, a bathroom, and desks, seems like a safe, if dreary, temporary resting place. As we go on, we learn that the initial estrangement occurred because Cathy and her siblings are the product of an incestuous union: their mother and their (late) father were half-uncle and niece. (In a later book it’s proven they are, actually, even closer relations.) As the four children languish, we slowly learn that their grandfather doesn’t even know they exist, and that their mother and grandmother have conspired to hide them until their grandfather’s death.

From here, as the mother visits less and less, virtually abandoning her children, the attic becomes a nightmare (or fantasy) of deprivation and desire. A string of hysterical events unfurls, including confrontations with the wicked grandmother, the violent consummation of Cathy and Chris’s incestuous longings, the fatal poisoning of one of the twins, and the near murder of all the children by their unhinged mother. After four years the three remaining children finally escape Foxworth Hall by their own devices, pale and stunted from years without sunshine, fresh air, or companionship. The rest of the series details the children’s lives as they become adults outside the attic, and Cathy’s rage-fueled obsession with exacting revenge on her mother and grandmother.

The writer and critic Douglas E. Winter, one of few to consider Andrews seriously and one of only a handful to interview her, describes the fantastical quality that’s central to the books’ appeal: “[The story] is animated by nightmarish passions of greed, cruelty, and incest, yet is told in romantic, fairy-tale tones, producing some of the most highly individualistic tales of terror of this generation.” Andrews herself picks up on this note later in the interview, saying about her own writing process: “I didn’t want a real horror, like a rapist or a murderer, but I wanted a fairy-tale horror.”

Returning to Andrews’s books as an adult, they retain their fairy-tale quality. As with re-reading favorite children’s books, the experience is like stepping into a dream. There’s a sense of déjà vu, as that which has been forgotten—not just the books but the whole world of associations they carry—becomes real again. But given the luridness and eccentricity of the books, the feeling is far from a cozy one. It’s a feeling many of us resist: Do we want to venture into that world again? Do we want to admit how much we loved that world or, worse, how much our desires, in fact, constructed it?

To acknowledge Andrews’s appeal, then, forces us to go to a place we visit in daydreams and poems but not in our normal, every-day, waking life—the semiconscious, half-remembered realm of children’s stories, fantasy, and fairy tales. And as anyone who’s read the unsanitized Grimms’ tales knows, this is not the candy-colored vista where Disney movies were filmed. As adults we try to forget that we ever visited this sinister place—the place where Cinderella’s stepsisters cut off their toes to fit into the glass slipper, where children were cooked and eaten in a gingerbread house, where Cathy Dollanganger was locked away in the towers of Foxworth Hall. But Andrews’s books remind us we’ve kept a hidden key to this world in our pocket all along. In other words, what makes us uncomfortable isn’t the feeling that, when we open the pages of Andrews’s books, we don’t recognize anything. Instead, we’re made uncomfortable because we recognize everything.

Freud wrote about this discomfort at remembering in his 1919 essay “The Uncanny.” He focused on the unusual etymology of the German words heimlich and unheimlich, both of which carry at least two seemingly contradictory meanings: of homely and familiar, but also of concealed, secret, kept from sight. The uncanny sensation derives from encountering not what is strange or distant from our experience, but rather its opposite—that which is close to home, familiar, intimate, but has been rendered unfamiliar through repression, and so we cannot access the source of that familiarity. The uncanny draws a map to what has been repressed. We feel the sensation when we encounter a person, an event, a situation that harkens back to something in our childhood—something prior to prohibitions, order, prior even to language. Suddenly, something that should have remained hidden returns. We react with dread or even horror. This is one reason why horror narratives involving dolls, imaginary friends, or other childhood relics are so successful in scaring us—they remind us of our childhood wishes, fears, and fantasies, which are often more complex, and much crueler, than we like to remember.

But the uncanny was also a fundamental part of Andrews’s initial appeal when we read her books as young adolescents. Encountering them at age twelve or thirteen, many of us were aware that something odd was going on, but it wasn’t the strangeness of the unknown. It was a familiar darkness, held tight in our chests since reading Hansel and Gretel. Reading Andrews, the repressed desires of childhood and the attendant fears of punishment for those desires were reactivated. The themes of fractured innocence, the dangerous family romance, parental fury—they all come hurtling back, a fairy tale gone to gorgeous rot. As Andrews told Winter, the fears she writes about are those lodged in us as children, the ones that “never quite go away: the fear of being helpless, the fear of being trapped, the fear of being out of control.”

In another essay, “The Relation of the Poet to Day-Dreaming,” Freud points to the power of creative writers to indulge our hidden desires—desires that are only otherwise given play in daydreaming, because they are somehow shameful. Somehow, the creative writer gives us license, assuring us that we are merely reading his/her personal daydreams, not ours, so we should feel free to take pleasure in them. Freud writes, “How the writer accomplishes this is his innermost secret; the essential ars poetica lies in the technique of overcoming the feeling of repulsion in us.” What makes Andrews so challenging, however, is that she makes us acknowledge what some of our daydreams were—and probably still are.

3.

Fundamental to Freud’s notion of the uncanny is the desire to repeat without knowing why. Andrews’s books both embody and indulge this desire. As repetitions shudder through her books, it’s almost as if Andrews threw her obsessions—abused and sexualized children, parentless homes, rape, revenge—up in the air and let them fall down in different places and configure new meanings. The most common strand is parents who either abandon or terrorize or seduce their children, leading to incest, tragedy, and the drive for revenge. Other recurrences are miscarriages, broken bones, falls and accidents, physical disabilities resulting from childhood neglect or abuse, and an obsession with hair. Central to many of the plots—and telling in a series of books structured on repetitions—are two contradictory ideas: memory as both permanently traumatizing and utterly malleable.

These repetitions fashion a dense network of associations and meta-associations, and it’s in My Sweet Audrina that Andrews’s obsessions reach their limits. Instead of one very complicated heroine (as in Flowers’s tormented Cathy), we have a pair of polarized girls: the passive, trusting, easily confused Audrina and her whip-smart, cunning cousin/sister, Vera. What was united in Cathy in Flowers becomes two characters in Audrina—a good girl and a bad one. And coincidentally or not, Vera and Audrina embody two highly typical responses to childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse: Audrina blacks out and forgets/denies the abuse ever happened, and even tends to deny that sex exists. But Vera, overwhelmed with rage, sexualizes everything. And in many ways, she’s the more sympathetic and compelling character. Her mockery of the weak and pallid Audrina is eerily dead-on. Vera tells the truth and is reviled for it—but that doesn’t make the truth any less true. Meanwhile, Audrina tries to deny her past, but it keeps coming back to swallow her up in its uncanny confusion.

The recurrent theme of sexual abuse reminds us that Andrews’s books didn’t exist in a vacuum. As much as we like to think the desires of teenage girls are timeless—puppies, horses, makeup—the 1970s and ’80s were, as an after-school special might have put it, a very special time. Stories about children in peril proliferated in this era, and for good reason. Considering the sexual revolution, the prevalence of drugs, a weak economy that led both parents to work outside the home, and a sky-high divorce rate, it’s not surprising that people were worried about the kids. Fears of the decay of the great American family hum through Andrews’s books.

But there’s also a more specific contemporary paranoia that finds expression in Andrews. Her tales of child abuse and incest hit American culture just as the first wave of survivors of real child abuse and incest starting telling their stories publicly. Influenced by an admixture of the women’s movement, new-age philosophies, and various self-help schools (and, maybe, Flowers in the Attic), survivors of abuse started coming out of the closet in the ’70s, often into a world that didn’t believe them, or if it did, preferred not to hear their stories. By the mid-’80s these stories had gathered into a howl from an underworld that mainstream America had to acknowledge. Those telling their tales of abuse were increasingly joined by those who claimed they had recovered deeply repressed memories of childhood atrocities. While many stood in a thoughtful middle, there were two extremes to the phenomenon: those who believed every formerly repressed story they heard, even elaborate tales of entire towns overrun with child-raping satanists, and those who discounted the entire idea of recovered memories. Andrews was at the forefront of this twilight world of the half-remembered and half-imagined—and she knew it.

“It was an odd sort of coincidence that I would start writing about child abuse right when it became very popular to write about it,” Andrews said in 1985. “There are so many cries out there in the night, so much protective secrecy in families; and so many skeletons in the closets that no one wants to think about, much less discuss. I tap that great unknown. I think my books have helped open a few doors that were not only locked, but concealed behind cobwebs.”

If her books tap into a child’s rage at his or her abuser, they also reflect the minefield of growing up in the ’70s and ’80s, when children faced problems their parents had no idea how to deal with: their parents hadn’t been divorced, they hadn’t gone to schools where kids sold dope in the halls, they hadn’t grown up with parents taking part in est trainings and other faddish self-help therapies. They’d had Margaret O’Brien as a role model, not problem-child poster-girl Jodie Foster. Parents didn’t know how to soothe their troubled children, but somehow V. C. Andrews did.

While Andrews’s novels scream with the cry of the abused girl, they also flicker with the uncomfortable feeling that our memories may also be fictions, stoked by wishes and fantasies. This tension makes the books less easy but more interesting. For all the sensitive books for young adults about abuse, for all the thoughtful after-school specials, it is Andrews’s books that speak to the complexities of such trauma on lower, and deeper, registers. The books bristle not only with survivors’ horror, but also with pleasure and desire. Abuse and incest are often glamorized, and punishment is always eroticized. There’s a strong sado-masochistic streak that speaks to power and its effects on the body with a rare understanding that Foucault couldn’t have explicated better. While Andrews denied she herself was a victim of abuse, she certainly had a keen understanding of its subtle operations within the family: the drive to repeat that which you swore you never would, the urge to love even those who have wronged you the most—and above all, the twin drives to forget and not forget, to say and not say.

When Flowers heroine Cathy’s grandmother forces Cathy’s beautiful mother to strip and show her children the wounds from a savage beating ordered by her father, the scene is attenuated, giving the horror and delectation plenty of room to stretch out and linger: “My eyes bulged at the sight of those pitiful welts on the creamy tender flesh that our father had handled with so much love and gentleness. I floundered in a maelstrom of uncertainty, aching inside, not knowing who or what I was.” Later, the mother slaps Christopher, the son who nearly swoons with mother-love for her, after which she draws him into a dreamy embrace. “Kiss, kiss, kiss, finger in his hair, stroke his cheek, draw his head against her soft, swelling breasts and let him drown in the sensuality of being cuddled close to that creamy flesh that must excite even a youth of his tender years.” She then “cupped his face between her palms and kissed him full on [the] lips.” Cathy watches, transfixed, and the text itself begins to break apart in erotic confusion: “And those diamonds, those emeralds [on her fingers] kept flashing, flashing… signal lights, meaning something. And I sat and watched, and wondered, and felt… felt, oh, I didn’t know how I felt, except confused and bewildered, and very, very young. And the world all about us was wise, and old, so old.”

In her book The Unsayable (2006), Lacanian psychoanalyst Annie Rogers writes about girls who’ve been abused, and the double drive both to speak about the abuse and to remain forever silent about it. “I wanted to tell… by not telling,” one girl relates to Rogers. This double drive is exemplified both in the writing of Flowers—which, while it revels in the telling, is fictional—and even more so in the adult reaction to it. We love to read the stories of the children’s punishment, and we loathe them. We revel in the incestuous scenes between Chris and Cathy, but we don’t feel very good the next morning. The books are compulsively readable, but judging by the mountains of Andrews titles at thrift shops, they are often disposed of soon after reading. Whether victims or not, those of us between, say, twenty-five and forty-five grew up in strange times, and her books uncannily fulfill our childhood fantasies while enacting our childhood fears.

Today, when it comes to abuse, forgiveness is popularly seen as paramount to healing, and while this idea has much merit, people often confuse it with a much easier, and unhealthier, path: that of burying the truth entirely. Andrews’s heroines, however, offer a different model, one in which the needs and desires of the victim are the beginning and the end. And the expression of rage, at least in the work of V. C. Andrews, is one of the victims’ greatest needs.

4.

Angry women drive Andrews’s books. In their world, blinding, murderous rage is an everyday emotion. But the fury of Cathy from the Dollanganger series stands out. Cathy forgets nothing, never forgives, and never apologizes. While brother Chris, despite his uncontrollable desire for his sister, generally functions as the book’s moral authority, Cathy does what she likes and pleases herself (echoing Wuthering Heights’s Cathy). She wants everything. She turns on the treacherous mother before any of her siblings do. She desires everything her mother has, and when she spots her mother’s young lover, she wants him, too. It’s pure unchecked oedipal hunger—and all justified by her mother’s cruelty and by the books’ own contorted, overheated logic. After she successfully consummates the primal fantasy of stealing her mother’s new husband (the ultimate father substitute), that’s still not enough. She wants to kill her mother more. Jane Eyre is clearly a model, but Cathy is far closer to that book’s Bertha Mason, the forgotten Other locked in the attic, waiting for her chance to wreak revenge in fire. (Foxworth Hall does, eventually, burn down.) Like their heroine, the books themselves lose the power to differentiate between revenge and madness. The rage of her mother and grandmother, both of whom feel wronged, irrevocably plants the seed in Cathy herself, who vows revenge and whose fury will eventually know no bounds.

While Cathy has justification for her wrath, she has no moral structure to contain or channel it. At the same time, there’s also something admirable, even enviable, about it. Unlike the “nice”methods of coping that young women are still routinely implored to use, Cathy never denies her rage or her sexuality (two major challenges for women of any age, let alone teenagers). Cathy is never “nice” or “good.” Even her love for her younger siblings is fiercely protective, never “maternal” or sentimental. A million girl-books, like Sweet Valley High, foreground the good girl, with whom we should identify, and the bad girl, whom we resist while vicariously enjoying her badness. Andrews’s books don’t combine these two girls so much as create an entirely new paradigm: a girl who is “good” and sympathetic but also very, very angry.

Female rage—especially the rage of young girls—remains an uncomfortable topic in our culture. It’s commonplace now to speak of male adolescent anger expressed outward with violence, and female adolescent anger expressed inward via eating disorders or Queen Bee–style social malice. But Andrews’s books and their appeal speak to a much deeper, darker shriek of girl-fury, and—like the reviewers who claimed not to even understand what Andrews was writing about—we may find ourselves averting our eyes.

The books’ persistent theme of anger and victimization born of mother-daughter rivalry, cruelty, and hatred is perhaps even more taboo than the sexual abuse the books gave a more overt voice to. Fairy tales swarm with instances of parental cruelty to children, of course, but what we see in the Flowers series brings it one (developmental) step further—a terrible dread of female identification: I hate my mother and most of all I fear I will become my mother. Increasingly her mother’s mirror image as she grows up, both in looks and in hot-blooded temperament, Cathy fixates on the idea—a not-unfamiliar feeling among girls and women, and the frequent subject of jokes and eye-rolling complaints. But the Flowers series shows that cultural punch line’s darker edges: Cathy’s mother, after all, seduced her own uncle and killed one of her own children. But she was also beautiful, wealthy, and powerful. Cathy’s fear is also her fantasy. Cathy wants her mother’s power over men, over her life—and especially over her own moral limitations, the petty petty mores that hold her back from taking everything she wants. It’s hard not to see a biographical parallel: Andrews said that, after finding an interested publisher who urged her to be “more gutsy,” she revised the book that would become Flowers by adding “unspeakable things my mother didn’t want me to write about, which is exactly what I wanted to do in the first place.” Andrews went on to dedicate the book to her mother, whom she claimed never read any of her books, or any books. “She thinks they’re all lies anyway,” Andrews said.

Then, behind Cathy’s identification, and her anger, too, is a demand for female power in any form, even its most violent. It’s a demand for self and a refusal of any notion of a sacrificing, compliant female; an embrace of career ambitions; a refusal of motherhood itself. “I never wanted to be an ordinary housewife,” Andrews, who never married, said. “I had no intention of getting married till after thirty, but life kinda threw me a curve. I think if I had failed at writing, maybe I would be bitter now. I always wanted to be somebody exceptional, somebody different, who did something on her own.”

When Cathy eventually becomes a mother, her children are, thankfully, sons. But eventually her horror and anger at the prison of motherhood emerges. Moving into a new home with her brother-husband, Chris, she walks up to the attic, the symbolic place of maternal punishment, and finds two twin beds, “long enough for two small boys to grow into men.” “Oh, my God!” thinks Cathy. “Who did this? I would never lock away my two sons.… Yet… yet, today I bought a picnic hamper… the very same kind of hamper the grandmother had used to bring us food.” She lies in bed that night with Chris, wishing she could be optimistic like him. Of course, she cannot: “But… I am not like [Mamma]! I may look like her, but inside I am honorable! I am stronger, more determined. The best in me will win out in the end. I know it will. It has to sometimes… doesn’t it?”

This is the flip side of rage—the examination of the qualities that one has in common with one’s tormentor. Cathy experiences that terrible feeling when she sees the beds, a feeling that she’s seen this before. She, like the reader, is lost in the fog of the uncanny and the unsayable, and trying not to look too closely at what she finds there.

5.

At the end of Flowers, the Dollanganger kids are out of the house, on the road, with some money in their pockets. Heaven ends on a similar hopeful note, and the series is overall much less dark than the other books. But Audrina, the most complicated and saddest of Andrews’s books, ends on an odd, flat note. Our heroine has found out the truth about herself (or has she?), and she’s stood up to her abusive father. But she’s decided to stay in her grand family home, with the people who’ve lied to and manipulated her for the past ten years. It’s unclear if this is out of concern for her mentally disabled sister, because she loves these people and wants to repair their relationships—or, chillingly, out of resignation. You can run, but you can never leave home—just ask Cathy, who at the end of the Flowers series dies in a replica of the same attic in which she began her story.

In fact, if you put the books together, you could fashion a single epic story, one in which the young woman from the big house may leave home, but always returns to it in the end. Cathy the Noble Avenger is also Vera, the Evil Stepsister. But Cathy the Survivor is also Audrina, the sad, lonely, confused “good” girl who doesn’t know the time of day, the year, or the truth about who she is. The girl for whom, in the words of the New York Times reviewer, “nothing else makes much sense”; the girl whose life unfolds, as Zoe Williams writes in the Guardian, like “the Brady Bunch describing a decade of orgiastic abuse”; the girl for whom, as the Washington Post has it, “[death] is the only way the child could remove [her]self from such a silly book.” The final lines of Audrina offer a chilling shorthand of the life of a misused child: “I wanted to scream, scream—but I had no voice.… I was the… Audrina who had always put love and loyalty first. There was no place for me to run. Shrugging, feeling sad… I felt a certain kind of accepting peace as Arden put his arm around my shoulders…. Arden and I would begin again in Whitefern, and if this time we failed we’d begin a third time, a fourth….”

The book ends on that sad, telling ellipsis.

If these novels speak to repressed female rage, to the complexities of desire and pleasure, to an ambivalence toward prescribed roles, then what little we know of the author’s own life story provides a plaintive echo. Injured in a fall at fifteen, Cleo Virginia Andrews (her initials reportedly inverted by her publisher because “V.C.” sounded “more male”) went on to develop crippling arthritis that kept her homebound for much of her life. Her mobility was further hindered by botched surgeries to fix the damage done by the fall. Completing a four-year correspondence course in art, she worked as a commercial artist and a portrait painter until she turned to writing at the age of forty-eight in 1972. With her mother, she moved from Virginia to Missouri and then Arizona to be near her brothers. But then, again with Mother, she moved back to Virginia, where—as her readers will have guessed—she spent the rest of her life in a big house, alone with her mother.

For a woman who craved excitement, who claimed, “I really wanted to be an actress. I think it’s very boring being one person,” such a life must have cut to the bone. Like a Victorian woman in the attic, she counted on her pen to let loose her demons. “I will pray to God that those who should will hurt when they read what I have to say,” her heroine Cathy asserts in Flowers’s prologue. “Certainly God in his infinite mercy will see that some understanding publisher will put my words in a book and help grind the knife that I hope to wield.”

Only two interviews with Andrews are available: one from People, in 1980, apparently so full of either lies or revelations that Andrews vowed never to do another, and a second one (for Douglas E. Winters’s 1985 book, Faces of Fear) in which she tries to set the story straight. In 1986, age unknown, the mysterious Cleo Virginia Andrews died of breast cancer.

Andrews’s editor, Ann Patty, is quoted in the New York Times describing the writer as “a very romantic woman schooled on fairy tales and soap operas who has a little hint of Bette Davis lurking around.” And in Faces of Fear she presents herself as a woman of great mystery: “I get older and younger as I want,” she says. She hints of precognitive powers and great erudition and grand schemes for the future, including directing films based on her books.

But the People interview tells a different story, and a much sadder one: “At 56 [Andrews later claimed they were wrong about her age], she has spent most of her life as an invalid in her Portsmouth, Va. home.… Stiffened joints confine her to crutches and a wheelchair.… She is flattered by gentleman callers, but discourages any serious romance while waiting to see if an operation suggested by her doctors will allow her to walk freely again.… She taught herself to embroider and sew, and makes most of her mother’s dresses.…”

“I couldn’t live without fantasy,” Andrews told People. “I can lose all my problems and make things the way I want them to be. That’s what you do when you write a book. You play God.”