When Elizabeth Bishop met Robert Lowell, in 1947, she had just published her first collection of poems, North & South. Lowell had just published his second, Lord Weary’s Castle, which later that year would win the Pulitzer Prize. Despite Bishop’s overwhelming shyness (she once described herself as “painfully—no, excruciatingly—shy”) they hit it off, so much so that the following year Lowell would come close to proposing to her (“Asking you is the might have been for me,” he wrote her a decade later, “the one towering change, the other life that might have been had”). And Bishop would later admit that she might have accepted.

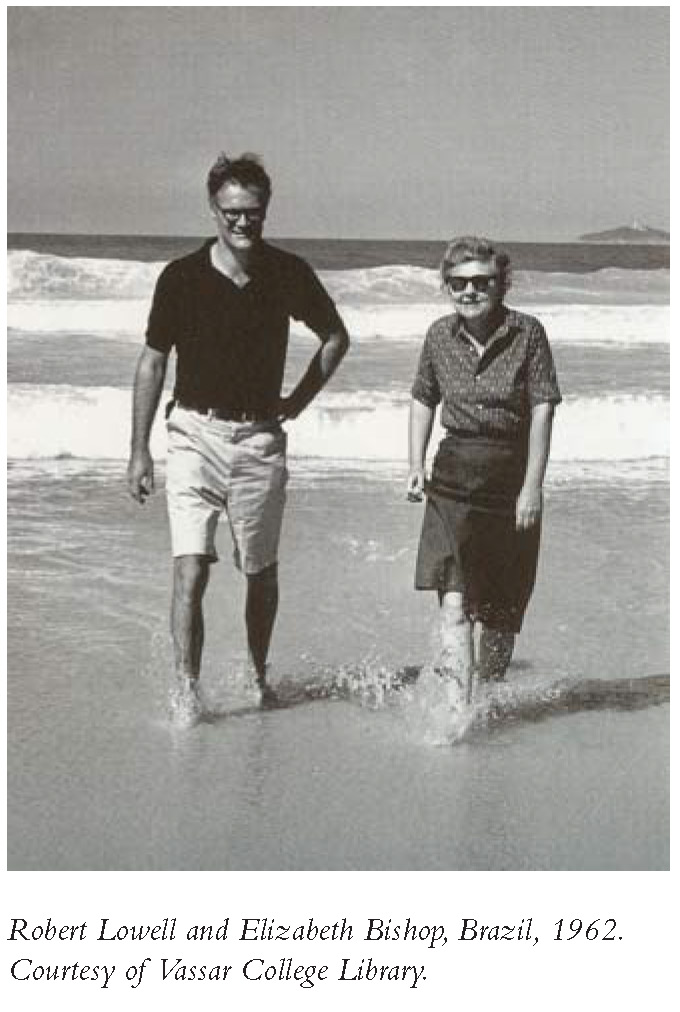

In 1951 Bishop moved to Brazil, where she lived with her partner, Lota de Macedo Soares, for the next eighteen years. Her relationship with Lowell was kept alive, though, largely through their letters—the pair exchanged nearly five hundred over the next three decades. (Their complete correspondence, from which this edited selection is drawn, will be published later this month by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.) The letters act as a kind of topographical map of the poets’ personal and creative lives. They chart Lowell’s periodic descents into psychosis, his three marriages, and his rise to become the most influential postwar poet in America. Of Bishop, living more quietly in Brazil, they offer elaborations on a sensibility that, combined with technical mastery, would cause her to win the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award. The letters also offer vivid glimpses behind the scenes of what poet James Merrill has called “her own instinctive, modest, lifelong impersonations of an ordinary woman.”

—Dominic Luxford

Briton Cove, Cape Breton

August 14th, 1947

Dear Robert,

(I’ve never been able to catch that name they call you but Mr. Lowell doesn’t sound right, either.) I had meant to write to you quite a while ago, to answer the note you sent me in New York, and I certainly meant to do it before your review of my book appeared in the Sewanee Review—but someone sent me the magazine so it is too late now. I agreed with your review of Dylan Thomas completely—his poems are almost always spoiled for me by two or three lines that sound like padding or remain completely unintelligible. I haven’t read [William Carlos Williams’s] Paterson but your review is the first one that has made me feel I must. The part about me I was quite overwhelmed by. It is the first review I’ve had that attempted to find any general drift or consistency in the individual poems and I was beginning to feel there probably wasn’t any at all. It is the only review that goes at things in what I think is the right way.

Heavens—it is an hour later—I was called out to see a calf being born in the pasture beside the house. In five minutes after several falls on its nose it was standing up shaking its head & tail & trying to nurse. They took it away from its mother almost immediately & carried it struggling in a wheelbarrow to the barn—we’ve just been watching it trying to lie down. Once up it didn’t know how to get down again & finally fell in a heap. Now it seems to be trying not to go to sleep. It is dark brown and white with a sort of cap of white curly hair quite long.— The boarders & the children of the household are all pleading with Mr. MacLeod, the landlord, to keep it—such excitement.

I think I heard before I left New York that you had received the Library of Congress post [Consultant in Poetry] for next year, although I don’t believe it is mentioned in the notes in the Sewanee Review—if it is true congratulations and I hope it is an interesting job. Thank you again for your review and I hope I shall see you in New York sometime in the fall, or perhaps even in Washington.

I hope you’re liking Yaddo and I should like to hear about it sometime—I almost went there once but changed my mind.

Sincerely yours,

Elizabeth Bishop

[Postcard: Spotted Jew-fish—Municipal Aquarium—Key West, Florida]

611 Francis St.

[Key West, Florida]

December 21, 1948

Dear Cal:

These are the “Fish” [Bishop’s poem “The Fish”]—I have found an absolutely marvelous apartment—large, a screened porch up in a tree, & a view of endless waves of tin roofs & palm trees—I’m going to write you—type you—a letter as soon as I get unpacked. Do let me hear from you.

Yours—Elizabeth

Samambaia—place where I live, near Petrópolis. Rio [de Janeiro] is the address.

July 28th, 1953

Dearest Cal:

Well, Brazil is a much more unlikely place than Amsterdam, certainly, and I’d never have picked it. But it is a combination of circumstances that make it wonderful for me now, and it really looks as though I’d stay. By next spring I think I’ll be able to go away—probably to Europe, for about six months. The next trip will be to New York, for a winter, I imagine. But I don’t feel “out of touch” or “expatriated” or anything like that, or suffer from lack of intellectual life, etc. I was always too shy to have much “intercommunication” in New York, anyway, and I was miserably lonely there most of the time. Here I am extremely happy, for the first time in my life.

How is your health? Your spirits sound very good.

Give my love to Elizabeth [Hardwick, Lowell’s wife at the time]. With lots for yourself, as always,

Elizabeth

Here I am “Dona Elizabetchy.”—always first names. You’d be “Seu Roberto.” No, I guess having a degree, you’d be “Doutor Roberto.”

Samambaia, December 5th, 1953

Dear Cal:

Yes—I first saw about Dylan Thomas in Time, that awful magazine that you have to read here because it has the news first, at least. Then I got some letters. I suppose he had a cerebral hemorrhage or something, poor man. I liked him so much. Well, “like” isn’t quite the word, but I felt such a sympathy for him in Washington, and immediately, after one lunch with him, you knew perfectly well he was only good for two or three years more. Why, I wonder … when people can live to be malicious old men like Frost, or maniacal old men like Pound[.]

Well, I got a car, too—I guess since I wrote you. I think I’ll even enclose another bad picture that looks as if I were heading into the Andes in it, when as a matter of fact I can’t even get my license yet. I made enough on a story [“In the Village”] in the New Yorker to get it—a slightly second-hand MG, almost my favorite car, black, with red leather. It zooms up the mountains with the cut-out open, but really I only like speedy looking cars that I can drive very slowly.

Best wishes and love to you both.

Elizabeth

Samambaia, November 30th [and December 10], 1954

Dear Cal:

What a joy to hear from you! Heavens—I’ve felt much better ever since; I hadn’t realized just how worried I had been, I guess. I had heard vaguely, perhaps from Zabel [the literary critic Morton Zabel], about the death of your mother and felt I should have written about that but scarcely knew what to say and of course do not even now. But I am just so relieved to know you are safe & sound again and apparently cheerful and pugnacious, too.

Frost put on quite a good show at our fearfully ugly embassy auditorium. Then I asked him to lunch at the house of a friend of mine in Rio—a beautiful old house and garden that I thought he might like to see. The friend had invited, among others, Brazil’s “leading poet [Manuel Bandeira],” who’s an awfully nice man but who refuses to speak any English at all—Frost refuses to speak anything else—and they are both extremely deaf. So lunch was rather a strain, with me screaming away in any old language I could think of at one end of the table, and Frost’s daughter Lesley holding forth endlessly to some poor bored Brazilians at the other end—and Miss Mongan—about her daughter’s creditable marks at Radcliffe. Frost asked the hostess where she got the seeds for the beautiful flowers on the table and after screwing up her courage she said very loud and clear: “BURPEE.”

It is starting to get dark and I am up at my estudio without a lamp, and I don’t hear any signs of our generator’s being started, so I must clamber down the mountain and start it myself.

With much love and saudades as they say here, a very nice word that seems to include all the sentiments of missing friends in one.

Elizabeth

Samambaia,

May 20th, 1955

Dearest Cal:

I have just finished the Yeats Letters—900 & something pages—although some I’d read before. He is so Olympian always, so calm, so really unrevealing, and yet I was fascinated. Imagine being able to say you’d always finished everything you’d started, from the age of 17. And he is much more kind, and more right about everything than I’d ever thought—right, until the age of 65, say. And it’s too bad he discovered s-e-x so late, I feel. I have a theory that all this business of psalteries and chanting, etc., was because he was completely tone-deaf and even the normal music of spoken verse wasn’t too apparent to him, so he felt something was missing. This is based on an imitation Pound once gave me (I don’t know whether it was the time I went to see him with you or later) of Yeats’ singing, to show how tone-deaf he was. The imitation was so strange & bad, too, that I decided they were both tone-deaf.

I just went out and screamed LUZ! to the black mountains in a most un-Goethe like way (more like God) and miraculously someone down at the house heard me and turned on the generator. It is dark and cold and rainy. Sometime, sometime I do wish you & E. would visit me here.

With love,

Elizabeth

[April 1, 1958]

APRIL FOOL’S DAY

Dearest Cal:

It’s very cold and long swirling clouds of fog are blowing past the window and through the trees and re-coiling against the giant rocks above.

PR [Partisan Review] with your poems in it and your letter came in the same mail, and I was pleased to see them both but extra-pleased, naturally, to have a letter from you again. You do sound well, Cal, and I hope and pray you are getting better every day. Maybe you’re at home again now. McLean’s [McLean Hospital] is a good place, I think. I’ve been to see friends there and my mother stayed there once for a long time. However, I hope you don’t have to stay very long—the people in such places are so fascinating I think one begins to find the usual world a bit dull by comparison. The poems in PR look very impressive, I think. Of course, I love the skunk one [“Skunk Hour”]. Actually I think the family group [“Memories of West Street and Lepke,” “Man and Wife,” and “To Speak of Woe That Is in Marriage”] is the more brilliant, don’t you? You know there are several of our contemporary poets who always live in sanatoriums, feeling they’re the only sensible place for a poet to live these days[.]

Remember me to Elizabeth and the baby. She must be starting to talk, by now.

With much love as always, Cal[.] Send me some poems!

Yours,

Elizabeth

Rio—August 20th, 1961

Dearest Cal:

I feel awful about the Hemingway suicide; it seems to be the last thing he should have done, somehow. All the notices I have read have been so STUPID—including English ones that say he learned how to write conversation from “British understatement”! I’m sure he must have been very sick for several years—out of his head—perhaps you know?

Your Rousseau postcard came just at the right minute. I was working on a chapter about naturalists, the jungle, etc. LIFE is getting nervous about this—say they’re more interested in people than animals. However, I have just learned that the way to keep a coati, if you have one, out of mischief is to give him a hairbrush and he’ll spend hours brushing his own tail. These are darling, small, ring-tailed animals. I’ve seen quite a few pet ones—one I met, if you picked him up and said “Dorme, dorme” to him, would shut his eyes and pretend to go to sleep.

I’ve heard recently from Marianne, and she doesn’t sound well at all. I’m glad I’m going to see her. Her publishers seem to be treating her badly, as usual—“outwitting” her, as she puts it. “I never protest at being diminished, Elizabeth, but had I known I was being outwitted I would have disrupted the peace in any language known to me.”

With much love, and see you soon,

Elizabeth

Rio, January 8 [and January 23], 1963

Dearest Cal:

Carnival comes next. The songs are already being sung:

“Is that trembling cry a song?

Can it be a song of joy?

And so great a number poor?

’Tis a land of poverty.”

[“]And their sun does always shine,

And their fields are bleak and bare,

And their ways are fill’d with thorns.

’Tis eternal summer there.”

And it is hot as hell and thank heavens for our new air conditioners. It must have been over 100 last night. Brazil is torn between Christmas our-style and New Years their-style. Lota got most presents on New Years. They put up a huge—4 story high—Santa Claus, 3 dimensional, at the entrance to the Copacabana tunnel—horribly jolly in paint and plywood. We hate him, so that Sunday night, coming back from Samambaia, seriously considered shooting him full of holes with Lota’s revolver. Then we thought of some whimsical headlines: “Santa Claus Shot! Taken to Strangers’ Hospital (across the street). Occupying rooms 204, 205, and 206. End of Christmas Foreseen!”

I also had a letter from Flannery [O’Connor]—I had written her at last—that begins: “I was real pleased to hear from you.” Since you were here I have acquired—at a vegetable stand—a crucifix in a bottle, like a ship in a bottle—all the accouterments, gilded, and a rooster, nails, etc.—and I offered it to her. She said she’d like it—she’d been trying to write a story for a long time about a man who had the head of Christ tattooed on his back—she saw him in the papers. I think we have a lot in common …

Things seem extra-dull after your stay—however, I am getting down to work pretty well, I think—Please send POEMS.

With love,

E.—

Rio, November 26th, 1963

Dearest Cal:

I haven’t really anything much to say to you—the last days have been like a bad dream, of course—but I feel like writing you a note. Lota came home early from work Friday to tell me about Kennedy before I heard it on the radio. Although there’s been a radio and TV strike for a week or so and only the Ministry of Education radio keeps going. The papers all got out special editions that night. We were out and the sight of the crowds was awfully moving—the streets full of people, the newsstands mobbed, and many people crying openly. The grief here has been genuine, all right—they felt, rightly or wrongly, that Kennedy was a friend of Brazil’s. You know Brazilians are much more formal about death than we are now. I must have had fifteen or twenty telephone calls and quite a few calls in person—of “condolence.” They feel so much closer to their politicians than we do, too—all American[s] should feel as if they’d lost a relative, to their way of thinking.

With much love as always—

Elizabeth

Rio de Janeiro, August 27th [and August 30], 1964

Dearest Cal:

Thank you for your letter of August 10th. I started to answer it last night when Mary [Morse] telephoned from Petrópolis & read me Mrs. Bullock’s letter announcing the $5,000 [award from the Academy of American Poets]. I’m overwhelmed and surprised, and I’ll write her as soon as the letter gets down here. I do not deserve it—but I’ll try to, retroactively. However, since you said it was between [Archibald] MacLeish & me, I comfort myself with the thought that I’m sure I need it more than he does. (I’ve never quite recovered from his coming to Key West on a hired yacht.) I rarely try to work at night but last night I worked away at a poem about Robinson Crusoe [“Crusoe in England”] until after two …

I feel awful about Flannery. Why didn’t I go to visit her when she asked me to. And I hadn’t even met her, or answered her last letter. I feel awe in front of that girl’s courage and discipline. I have some wonderfully funny letters from her—one about Lourdes—. Lota just read me a bit from the morning paper that Flannery would have liked: there was a fist fight in the Rio Chamber of Deputies. One Deputy who is also a priest held another Deputy in a head-lock to keep him from hitting a third Deputy, and the man screamed (the usual phrase to any priest here) “Bless me, father, bless me! Let me hit him!”

With much love as always—

Elizabeth

Ouro Prêto, June 15th, 1970

Dearest Cal:

I hope you received my postcard on which I said I was accepting the Harvard job—your job, that I’m sure you are responsible for being offered to me[.]

I am having a lovely time just being lonely—perhaps it is the way I should live, anyway. I am so damned cheerful all the time I can’t believe it—I have told my 18 year-old maid that she shouldn’t be frightened when I laugh to myself (at my own witticisms) and talk out loud—it is my way of “working.” I play her the Beatles and Janis Joplin and Sambas all day long and we both go about this large house dancing—it is very nice—and the house is so beautiful I can’t dream any more of selling it. You must see it some day—even if you are not domestic, like me.

With much love, and gratefulness always,

Elizabeth

[Cambridge, Massachusetts]

October 14th, 1971

Dearest Cal:

The classes—so far so good, I think. The poetry class much more advanced than last year—almost too much so—many have published poems & tend to “know what they want to do” only too well[.]

When I woke up this morning I was dreaming I was back in the Galápagos—and that’s really where I’d like to be, I think—not for a very long time, but for longer than we were up there. It and the Amazon are the best things I’ve ever done, I think …

I’d like to see your new poems. I’d love to see you.

With much love always,

Elizabeth

*

From Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, edited by Thomas Travisano with Saskia Hamilton, published this month by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Writings of Elizabeth Bishop copyright © 2008 by Alice Helen Methfessel. Compilation copyright © 2008 by Thomas Travisano. Editorial work copyright 2008 by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, LLC. All rights reserved.