At its best, the celebrity profile fosters a feeling of warm intimacy. We read the profile, and we feel we have been granted access not just to the contents of the celebrity’s overnight bag but to the contents of his or her heart. Yet this same profile simultaneously manages to reveal no new information. We love it because it confirms our best beliefs. No other form so seamlessly constructs the necessary components of celebrity, exploiting the desire to see our idol as both “just like us” and nothing like us, as both the girl next door and a goddess above. It is, in other words, spectacularly banal.

Yet the celebrity profile serves a crucial industrial function: it sells the media products in which the celebrity appears; it sells the magazine that publishes the profile; but, most important, it sells the celebrity’s image and the values that image is made to represent. A profile of Robert Downey Jr. labors to reinforce the central tenets of his image (the phoenix-like return, the affability, the specter of his party-boy youth); a profile of Jennifer Lawrence convinces us that the joking, off-the-cuff, cool-girl charisma we see in her post–Oscar win interviews is not a performance but her authentic self. Each profile is almost eerily on message: Ryan Gosling is introspective; George Clooney is charismatic.

The trick, of course, is to make it look like the profile is not selling anything. It’s just a chat between friends, or a nonchalant trip to the desert to get tipsy, engage in some “real talk” that sets forth the celebrity’s most winning attributes, and meander to a discussion of his or her upcoming project. This elision is crucial to the celebrity process writ large: we want to believe that these celebrities give of themselves willingly, not because of economic imperative.

These tensions within the celebrity profile—selling oneself versus erasing evidence of the sale, generating intimacy while disclosing nothing—have structured the profile for decades. And the profile of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century enacts a return to the publicity style of classic Hollywood, when the studios found raw “star material” in the form of pliable young talent, packaged it, labeled it with prefabricated type, and sold the star in a meticulously mediated bundle to the American public.

*

In classic Hollywood, the publicity apparatus—fan magazines, gossip columnists—worked in concert with the studios. A profile was constructed using biographical sketches provided by the studio itself, mixed with quotes the star may or may not have provided, and thoroughly vetted, before making its way to audiences. For example, a 1928 Photoplay profile of silent-movie star Clara Bow, “as told to” Adela Rogers St. Johns, was serialized over three months and spanned twenty-two pages, promising “the touching human document of a tragic child who became the very spirit of gayety.” The piece was a routine work of melodrama, with vivid descriptions of Bow’s impoverished Brooklyn youth, her mentally ill mother, her dramatic move to Hollywood, and the difficulties she faced trying to break into pictures with her tomboy physique.

It was also a public-relations marvel, further piquing interest in Bow—who, with her turn in the smash hit It, was quickly becoming the biggest star in Hollywood—while engendering enormous sympathy for the star. As Bow dramatically proclaimed, “I am a madcap, the spirit of the Jazz Age, the premier flapper, as they call me. But no one wanted me to be born in the first place.” Future profiles would rely heavily on this sympathy, and its attendant understanding of Bow’s tragic childhood, to excuse all matter of unbecoming star behavior, including a series of broken engagements, a mass of gambling debts, and weight gain.

In the ’20s and today, the profile functions as the celebrity urtext, setting and resetting the tone and tenor of the celebrity’s image. Done correctly, it can be wielded to right all matter of public wrongs. The banality, for the most part, persists, as does the careful calculation, the stink of the highly vetted, all-parties-approved text. But it hasn’t always been that way.

The profile and its public-relations power were by no means limited to the Hollywood star, or even to the twentieth century. Historian Charles Ponce De Leon dates the emergence of personality journalism to the development of the “public sphere” in the late eighteenth century, when “virtually any man could be famous—could become a public figure known to a large number of people.” A man needn’t be a member of the aristocracy or even from a well-to-do family; he just needed to be public. He could be a writer or a politician, a captain of industry or an actor. But with public visibility came the need to manage that publicity—to author the public self, as it were. Thus: autobiographies, commissioned biographies, interviews. Think The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, which, with its healthy dose of quips and bon mots, helped solidify Franklin’s reputation as both a politician and a Renaissance man.

But the spread of the public sphere was concomitant with growing skepticism toward the public self. As public personalities became increasingly aware of the importance of image, and of their performance thereof, the public naturally developed a consciousness of (and wariness about) that performance. A public speech, a photo op, a self-penned editorial—they were compelling, they made the subject seem amiable or eloquent or stately, but they were also highly calculated. Even a layperson knew this.

If the public sphere connoted performance, then the private sphere suggested authenticity. In the home, surrounded by intimates, the public personality could show his “true self.” In this way, the celebrity profile, a form which began to coalesce with the spread of the mass-circulation press in the late twentieth century, gradually began to include vignettes of the “great man” at home, interacting with his children, engaging in hobbies, just being “real.” Of course, the characteristics of the celebrity illuminated within the domestic sphere never contradict the preestablished, public characteristics. Rather, they serve to validate what we already believe. Put bluntly, Angelina Jolie’s public image is sex, thus her private image is set in the bedroom.

The sustained focus on the personal and the domestic was also an expression of an overarching shift in what Americans valued in public figures—a shift, in Leo Lowenthal’s words, from “idols of production” to “idols of consumption.” According to Lowenthal, over the first quarter of the twentieth century, profiles covered men (and an occasional woman) who did things—invented products, incited change, and offered commentary, through various means, on “decisive social, commercial, and cultural fronts.” These idols of production were men and women of substance, whose “life stories are really intended to be educational models.”

But around 1920, the focus of the profile began to shift. Gradually, publications replaced the men of action and industry with sports figures and entertainers, related, either directly or indirectly, to leisure activities. These “idols of consumption” amount, in Lowenthal’s somewhat jaundiced opinion, to “a caricature of a socially productive agent.” Narratives focus on hobbies, food and drink preferences, and personal habits: President Taft “doesn’t smoke”; baseball player Hank Greenberg “lives modestly with his parents”; newspaperman Silliman Evans specializes in “large-scale outdoor entertainment.” Details previously considered gauche—or, at the very least, relegated to the society columns—became prime profile fodder: the cost of parties, the provenance of furs, the exotic dinner courses, the ornate details of the celebrity’s home.

These idols do not create; they consume, or so suggested the profile. By focusing on the minutiae of their private lives, these pieces transformed subjects who wrote, ran, spoke, and otherwise proactively engaged in society into the sum of their consumption patterns. In so doing, they also provided a very different model for the reader. If “idols of production” encouraged citizens to become the architects of industry, then “idols of consumption” directed them to become its fuel. And by presenting these subjects in the guise of leisure, the profiles ironically encourage the reader to work harder—if only so as to gain a position from which that type of leisure becomes available. Within this paradigm, work is no longer valuable in and of itself but as a means to an end: toward consumption and leisure, which will then require more work to extend, and so on, and so on.

One can see how Lowenthal, a Marxist and member of the Frankfurt school, would find this shift rather abhorrent. It certainly wasn’t without context: the 1920s marked the rise of advertising culture writ large and conspicuous consumption habits that extended far beyond the realm of the profiled celebrity. But the celebrity profile, like all other popular media products that attend an era of overarching societal change, was both a reflection and an accelerant of that change.

The focus on consumption was also convenient: in a publishing industry increasingly dependent upon advertising dollars, celebrating the spending patterns of public figures prepares readers to spend money, albeit on a markedly reduced level, on the products advertised alongside the profile. The suggestion was made explicit in fan-magazine advertisements, many of which featured a star, oftentimes the subject of a profile elsewhere in the magazine, endorsing Lux soap and other domestic products. For her next picture Joan Crawford might have a wardrobe costing thousands, but she also needed to use face soap—a soap that we, too, could purchase, thus aligning ourselves, however distantly, with the glamorous star before us.

*

And so, for the first half of the twentieth century, consumption—along with other leisure activities, including sport and romance—structured the celebrity profile. As a general rule, profiles were flattering and banal in the way that florid descriptions of drapes and romances can be. Which isn’t to suggest that the press of the period was wholly without titillation. It was simply the provenance of the gossip columns, where Walter Winchell, Jimmie Fidler, Mike Connolly, Hedda Hopper, and Louella Parsons passive-aggressively needled stars and other members of “café society” with various levels of discretion and coded language.

In a fan magazine, for example, a profile in the beginning could fawn over a star, while a gossip column at the end could allude to his or her misbehavior, a new dalliance, or a rumored pregnancy. The gossip column could whisper and titillate; the profile narrativized past behavior, explained, and made things right—usually with the direct input of the star’s studio or personal press agent. Sometimes, as in the case of the first fan-magazine piece following the revelation of Ingrid Bergman’s affair with Italian director Roberto Rossellini, it was even penned by the press agent, which the profile labors to portray as a confidante with intimate knowledge of the star, her past, and the motivations for her decisions.

This level of oversight and calculation created prose that was generally stiflingly boring. A 1956 profile by Pete Martin in the Saturday Evening Post, for example, promised a “surprisingly candid report on the girl with the horizontal walk,” also known as “the New Marilyn Monroe.” Yet the text simply recycled the details of Monroe’s biography and dissected her into “the sex pot Marilyn,” “the frightened Marilyn,” and “the New Marilyn,” a “composed and studied performer.” We finish the three-part profile, spanning more than twenty pages, with the distinct feeling of enduring half an hour of spoon-feeding. The photos, at least, are entertaining.

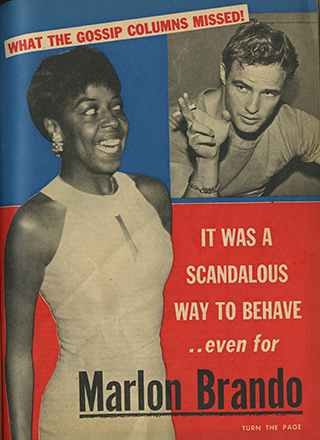

But during this same period, a cluster of events within the journalism world dramatically changed the tone and tenor of the celebrity profile—a change that would persist for the next twenty years. The first was the rise of Confidential magazine, a garish, pulpy scandal rag that, over the course of four years, indicted a broad swath of popular figures for scandalous behavior. The magazine promised to “tell the facts and name the names”—which it did, with addictive bombast, to an audience that quickly reached over six million.

Confidential was by no means the first publication to suggest that its subjects lived secret, salacious lives—the tabloid press had thrived, in various iterations, for years. But Confidential’s dirt was richer: publisher Robert Harrison developed a web of informants crossing the continent. More important, he understood what titillated: miscegenation, homosexuality, unbridled female sexuality, and communism. Confidential’s photos were black and white, decoupaged onto backgrounds of red, yellow, and blue, with exclamatory headlines and suggestive photo captions. Harrison cloaked these topics in heavily punned innuendo—Liberace, for example was “Mad About the Boy!” while another cover promised to reveal “What Makes Ava Gardner Run for Sammy Davis Jr.” An outtake of Gardner and Davis, captioned “Ava sat glassy-eyed through a gay tour of Harlem with Sammy. Said a bartender: ‘Another round and she would have been plastered,’” took on suggestive meaning from the photo’s actual context. No one was immune: Frank Sinatra was donned the “Tarzan of the Boudoir” after a visiting maid reported that his sexual stamina stemmed from a steady diet of Wheaties; another article revealed “The Girl in Gregory Peck’s Bathtub,” also known as Veronique Pasani, the French reporter for whom he had purportedly left his wife. Some of it was rooted in truth; some of it was extrapolated on what Harrison knew audiences wanted to be true; all of it was deliciously bombastic.

Celebrity profiles had attempted to offer access to the authentic by focusing on the domestic and the personal. Confidential also promised access to the authentic, only it did so by illuminating the hidden, the secret, and the sexual, which, as Michel Foucault would remind us, is what Western civilization considers the most authentic site of identity. We are, in other words, what we do in the bedroom. Confidential didn’t listen to publicists; it spurned the demands of the studios. Harrison was a rogue agent, refusing to operate by the rules of the celebrity coverage, which entailed keeping the piece, and the image of celebrity, positive. If access to the celebrity meant a profile that was flattering, recuperative, and boring, then Harrison wanted none of it. In abandoning access to the public persona, Harrison likewise abandoned the imperative of banality.

Confidential, however, did not operate in a vacuum. The slow unraveling of the studio system over the course of the 1950s meant that more and more stars were operating outside the constrictive yet protective arms of the studio. Before, the studio’s publicity apparatus was there to provide copy and censure an unflattering profile before it went out—if a publication dared to publish unsanctioned material, then that studio would refuse to provide access to the rest of its contracted stars. Break the rules on a profile of Clark Gable, for example, and lose access to the formidable stable of MGM talent.

The studios let loose their “stables” of contracted labor, but it wasn’t the end of the movie star. Rather, the stars went freelance, acquiring agents, press agents, and lawyers to perform the work that the studio had done for them. Each star, in other words, acquired a mini–publicity department for him- or herself. But even a powerful agent was somewhat powerless against a publication, such as Confidential, with seemingly nothing to lose. Even the formidable Henry Willson, the man behind Rock Hudson, Tab Hunter, and a slew of similarly beefcaked male stars, couldn’t entirely shield his clients. When Harrison obtained evidence of Hudson’s homosexuality, Willson was able to kill the story only by sacrificing the reputation of another of his clients, Rory Calhoun, who had covered up his past as a juvenile delinquent.

*

Crucially, Confidential didn’t cover just Hollywood stars. The decision to put Marilyn Monroe on the cover of an early issue helped boost sales, but the magazine’s content comprised equal parts stars and general-interest celebrities: politicians, government officials, singers, and socialites. At the same time, the fan magazines, whose singular focus had been Hollywood stars, began to cover teen idols, television personalities, and Jacqueline Kennedy. The lines between fan magazine and scandal rag were blurring, but so, too, were those that had long separated the high-, middle-, and lowbrow press. A blatantly pornographic magazine like Playboy was suddenly posturing as “gentleman’s journalism”—and the New Yorker was profiling Marlon Brando, a major Hollywood star.

This profile, entitled “The Duke of His Domain,” was penned by Truman Capote and published in the November 9, 1957, issue. Capote met with Brando in Kyoto, Japan, where he was filming Sayonara, and spent several hours drinking and conversing in Brando’s hotel suite. Over the course of the interview, Brando ate, pontificated on his childhood and the state of Hollywood, ate some more, and repeatedly told Capote not to believe a thing he said. It’s a tremendously compelling read—and an absolutely damning piece of celebrity journalism.

Capote employs the practiced tropes of the celebrity profile, only he allows them to become subtle caricatures, both of themselves and of Brando. Where the author would usually provide details of the star’s favorite foods as a flattering avenue toward illumination of his soul, Truman lets Brando’s diet consume him:

“I’m supposed to be on a diet. But the only things I want to eat are apple pie and stuff like that.” Six weeks earlier, in California, Logan had told him he must trim off ten pounds for his role in “Sayonara,” and before arriving in Kyoto he had managed to get rid of seven. Since reaching Japan, however, abetted not only by American-type apple pie but by the Japanese cuisine, with its delicious emphasis on the sweetened, the starchy, the fried, he’d regained, then doubled this poundage. Now, loosening his belt still more and thoughtfully massaging his midriff, he scanned the menu, which offered, in English, a wide choice of Western-style dishes, and, after reminding himself “I’ve got to lose weight,” ordered soup, beefsteak with French-fried potatoes, three supplementary vegetables, a side dish of spaghetti, rolls and butter, a bottle of sake, salad, and cheese and crackers.

Food still offers insight into character, but here that character is undisciplined and overindulgent. Elsewhere in the profile, Capote simply lets Brando talk: “When I talk to my friends, we speak French. Or else a kind of bop lingo we made up.” Given the correct context, the statement could be given a light touch—or made to seem like Brando was making fun of himself or what he had come to represent. Without that context, it reads as so earnest and tone-deaf as to be farcical.

Star talks; author listens and, eventually, writes. That had long been the dynamic of the celebrity profile, with the implicit goal of promotion cloaked in intimate, off-the-cuff, non-promotional conversation between friends. Ostensibly, Brando and Capote were dancing the same dance. But reading the product felt like actually peering into the star’s dirty closet—in no small part due to Capote’s overarching sense of wit and irony. Not the dirty closet that he had cleaned up, leaving a few chance objects to look dirty, but the actual, embarrassing, abject experience of the celebrity lifestyle

“The Duke of His Domain” became a watershed moment in both Brando’s and Capote’s careers. After the phenomenal Broadway success of A Streetcar Named Desire, Brando had brought Method acting—and his peculiar attitude toward publicity—to Hollywood. He refused to join a studio or sit for interviews with the fan magazines; he abhorred the old-biddy gossip columnists; he wore jeans; he dated non-starlets; he hung out with black people. He was an anti-star who was anti-publicity, which, of course, was publicity in and of itself.

The magnitude of his talent buoyed him in Hollywood: he might not have played by the rules, but he made it seem like everyone else was playing an old, outmoded game. Streetcar, Viva Zapata!, Julius Caesar, On the Waterfront—four years, four Academy Award nominations, and finally, for Waterfront, a win.

But then things began to slow down and sour, if only slightly. Brando’s self-seriousness was beginning to stink. What Capote’s profile did, then, was reproduce the same sort of statements and monologues that had long typified Brando profiles—only now they seemed fatuous. Brando, who had trumpeted his disdain for Hollywood and its assembly-line approach to art, now seemed just as hollow as the glitziest studio starlet.

It wasn’t a scandal, per se. Brando wasn’t caught smoking weed like Robert Mitchum was, nor did he run off with an Italian, à la Bergman. The difference was that those stars had created their own scandals; the press simply covered the reactions. Here, however, an established author was the catalyst. It wasn’t libel; it wasn’t untrue. But it certainly wasn’t sycophantic, nor was it banal—because Capote had envisioned a different paradigm for what a celebrity profile could or should do.

He wanted, as he told the editor of the New Yorker, to take the “very lowest form of journalism,” that is, the interview with the movie star, and transform it into a “new genre.” He would apply “the technique of fiction, which moves both horizontally and vertically at the same time: horizontally on the narrative side and vertically by entering inside its characters.”

Capote’s technique wasn’t unlike Brando’s own Method acting, which also aimed to arrive at a more sophisticated understanding of human character through psychological realism. But what made Brando’s characters so compelling was their complex mix of light and darkness—they were sympathetic yet despicable, emotionally strong yet morally weak. By using similar tactics on Brando, Capote illuminated the same psychological poles within the actor.

In this way, Capote didn’t show just a different side of Brando but a different depth to the celebrity profile. Most important, it was an unflattering portrait. Under the shelter of the New Yorker and with an established career and connections, Capote could afford the backlash. So what if Brando threatened to kill him? His profile, and what it suggested of Brando, was all anyone was talking about.

Capote’s profile also signaled what would soon become a shift in journalism at large, away from the “traditional” techniques of reportage and toward an overarching commitment to realism, generally referred to as “the New Journalism.” In his 1973 anthology, The New Journalism, Tom Wolfe retrospectively outlines the history and parameters of the genre, which he situates as a natural response to what he terms “the retrograde state of contemporary fiction.” In the early ’60s, a motley group of journalists, most of them in their thirties, many of them writing for the New York Herald Tribune, discovered, in Wolfe’s words, “that it was possible in non-fiction, in journalism, to use any literary device, from the traditional dialogisms of the essay to stream-of-consciousness, and to use many different kinds simultaneously, or within a relatively short space… to excite the reader intellectually and emotionally.”

This new, “subjective” journalism espoused techniques of realism, including scene-by-scene construction, recording dialogue in full, and “third-person point of view” that “giv[es] the reader the feeling [of] being inside the character’s mind.” It also employed heavy use of deep description—the “recording of everyday gestures, habits, manners, customs, styles of furniture, clothing, decoration, styles of traveling, eating, keeping house, modes of behaving toward children, servants, superiors, inferiors, peers, plus the various looks, glances, poses, styles of walking and other symbolic details that might exist within a scene”—which, together, symbolized the subject’s “status life,” lending the piece the “absorbing power” of the best fiction.

Today, these characteristics don’t seem that radical, but that’s because the tenets of the New Journalism have so thoroughly pervaded contemporary journalism. The excerpts collected in Wolfe’s anthology—from Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Hunter S. Thompson’s “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,” and Wolfe’s own The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test—read like the syllabus of a journalism master class. These writers were applying techniques of high art to low culture: horse races, drug trips, Hells Angels, marijuana use. And otherwise-serious subjects—the war in Vietnam, Martin Luther King, serial killers—suddenly seemed electric. This wasn’t staid reportage; it wasn’t fawning or careful. It was dangerous and messy and vital; it had a pulse.

Applied to the celebrity profile, the New Journalism transformed the banal into an art form. Kenneth Tynan’s profile of Marlene Dietrich, “Two or Three Things I Know About Her,” for example, reads more like the lyrical, theoretical musings of Roland Barthes than a celebrity profile:

What we have here, by way of summary, is a defiant and regal lady with no hobbies except perfectionism, no vices except self-exploitation, and no dangerous habits except an infallible gift for eliciting prose as monumentally lush as this from otherwise rational men. Marlene makes blurb-writers of us all. She is advice to the lovelorn, influence in high places, a word to the wise, and the territorial imperative. She is also Whispering Jack Schmidt, Wilhelmina the Moocher, the deep purple falling, the smoke in your eyes, how to live alone and like it, the survival of the fittest, the age of anxiety, the liberal imagination, nobody’s fool and every dead soldier’s widow. On top of which, she has limitations and knows them. She is now on public show in person for the first time in New York. Roll up in reverence.

Tynan, a New York–based theater critic, was friends with Dietrich—a friendship evident within his piece. “Marlene relishes the breath of power,” he writes. “She is rabidly anti-war, but just as rabidly pro-Israeli. This paradox in her nature sometimes worries me.” But as evidenced throughout his prose—and in his profiles of other confidantes and collaborators, most famously Roman Polanski, with whom he cowrote the script for the ill-fated adaptation of Hamlet—actual rather than feigned intimacy leads to a profile that’s at once perceptive, analytical, and unabashedly subjective. But that subjectivity—that singularity of perception—is what lends the profile its potency.

*

One didn’t have to be friends with the stars to write about them. Rex Reed’s “Do You Sleep in the Nude?,” a profile of aging star Ava Gardner, serves as the lead essay to The New Journalism collection. Much like Capote’s profile of Brando, it flips the genre on its head. Reed describes her “Ava elbows” and declares her “gloriously, divinely barefoot,” claiming that “at forty-four, she is still one of the most beautiful women in the world.” But Reed also manages to make her look like what today’s gossip columnists would call a “hot mess.” After kicking her press agent out of the room (“Out! I don’t need press agents!”) she queries Reed: “You do drink—right, baby? The last buggar who came to see me had the gout and wouldn’t touch a drop.” She then pours herself a “champagne glass full of cognac with another champagne glass full of Dom Perignon, which she drinks successively, refills, and sips slowly like syrup through a straw.”

The whirlwind interaction that follows—in which several men come to call and the assembled group leaves the hotel room, avoids swarms of autograph-seekers, and retreats to the Regency Hotel bar—seems to oscillate, dreamily, between Gardner’s cynical analysis of her career and palpable evidence of her charisma. When Reed asks of her tenure at MGM, she responds, “Christ, after seventeen years of slavery, you can ask that question? I hated it, honey. I mean, I’m not exactly stupid or without feeling, and they tried to sell me like a prize hog. They also tried to make me into something I’m not then and never could be.” After Gardner declares, “I’ve never had a good man,” Reed asks after her exes. Hearing ex-husband Frank Sinatra’s name, Gardner responds, “No comment,” but when Reed follows up concerning Sinatra’s new wife, Mia Farrow, Gardner’s “eyes brighten to a soft clubhouse green. The answer comes like so many cats lapping so many saucers of cream. ‘Hah! I always knew Frank would end up in bed with a boy.’”

More booze, more quips. Then, suddenly, Gardner’s out the door, taxiing her way across town, “fading into the kind of night, the color of tomato juice in the headlights, that only exists in New York when it rains.” The profile is barely nine pages long, but it wallops the reader with a heady dose of hubris and despair. In Reed’s hands, Gardner, one of the last remaining vestiges of classic Hollywood, appears resilient, beguiling, but ultimately broken by the very system that created her.

It doesn’t feel as if Reed’s manipulating us. The rhetorical devices are mostly invisible. Rather, Gardner, like Brando, implicitly indicts her profession and the fandom that supports it—Reed just had to provide the audience. And as with Capote’s profile, the results are damning: instead of propping up the illusion of celebrity superlativeness, it punctures it.

*

Film critic Pauline Kael criticized the New Journalism for being “non-critical.” It gets people excited, she explained, but “you are left not knowing how to feel about it except to be excited about it.” It’s easy to concede Kael’s point in relation to the New Journalism about general subjects. Yet when it came to celebrities, New Journalism profiles were always critical: of celebrities, but more incisively, if subtly, of the society from which they sprung. Whereas the traditional profile talked down to the reader, the new celebrity profile spoke to a reader with the understanding that celebrity is artifice, life is performance, and the function of the profile was not to make us forget these facts but to remember them. Interrogate them. Even be frightened by them.

It’s not surprising that celebrities themselves—and their agents and publicists especially—were also frightened by this type of journalism. One profile could effectively unravel years of image construction and, even worse, make that construction seem laughably shabby. This fear was amalgamated by the logistics of the era, as the ’60s and ’70s were a tenuous time to be a celebrity. The puzzle-work of Hollywood seemed to be changing daily, as new multinational conglomerates bought old studios and, finding the movie business less than lucrative, sold them for parts.

Stars were both one of the few ways to predict a hit picture and not predictable enough in practice. Julie Andrews turned The Sound of Music into the surprise hit of 1965, but Star! (1968) proved a costly mess. Barbra Streisand was the hottest thing in Hollywood in 1968 following the runaway success of Funny Girl; one year later, Hello, Dolly! barely broke even. The old Hollywood guard was dying or washed-up, replaced by television stars and the likes of Peter and Jane Fonda, Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, and Dennis Hopper, who eschewed the traditional models of stardom, with their attendant understanding of what a star could and could not do—and could and could not say—in public.

The New Journalism matched this ethos and reproduced the fashionable attitude toward celebrity. If celebrities were one more manifestation of Guy Debord’s “society of the spectacle,” the very embodiment of what Daniel Boorstin called “the pseudo-event,” then “good” journalism shouldn’t further that cause but explode it. Some stars resisted that impulse, while others participated in the destruction of their own auras: Jack Nicholson dishing on his drug use to Playboy, for example, or Jane Fonda broadcasting to the Viet Cong. They were still celebrities, but their images, and the journalism that helped create them, were a far cry from the pablum of the past. At the same time, the magazines that had served as the primary home for the traditional profile—Photoplay, Modern Screen, the Saturday Evening Post, Look, and Life—were either in steep decline or ceasing publication.

But at some point in the ’70s, the verve of this New Journalism began to exhaust itself. Blame it on the success of People magazine, which, following its debut, in 1974, quickly reached a circulation of three million—a figure that had taken its sister publication, Time, over thirty years to reach. People employed a style of “personality journalism” that aimed, according to its editors, for stories that would be “light and lively, easy to read and heavy on photo content.” It wasn’t a magazine of celebrities or politicians but of “people,” broadly conceived, each with their own story of broad human interest. It was, in other words, a sharp reversion to the banality of yore.

*

Or blame it on the rise of the superagent and the master publicist. Agents were by no means new to Hollywood: by the early ’70s, Lew Wasserman and the Music Corporation of America (MCA) had quietly dominated Hollywood for decades, but the “superagent” was something new. Industry analysts trace the origins of this new breed of agent to 1975, when Michael Ovitz and four William Morris colleagues combined to form the Creative Artists Agency (CAA). Following Ovitz’s lead, CAA agents dressed in Armani suits, drove matching Jaguars, traveled in packs, and practiced a Zen-influenced philosophy of teamwork and collaboration. In hindsight, it all seems very, very ’80s.

But over the course of the decade, CAA rose to prominence and power, becoming home to the most vaunted talent brokers in the business. Ovitz steadily built his client base and industry influence, signing a laundry list of major stars and, in 1981, an unknown named Tom Cruise. Over the course of the ’80s, Ovitz secured roles for Cruise in a string of massive hits that fine-tuned Cruise’s cocksure, all-American, and definitively masculine image. Cruise relied heavily on Ovitz and CAA during this time: they packaged him with Paul Newman in The Color of Money; they found the script for Rain Man, put Cruise and fellow CAA client Dustin Hoffman in the lead roles, and sustained the project through four changes in director. By 1990, Cruise was arguably America’s biggest star, with a corresponding price tag of nine million dollars a picture.

Cruise had undeniable charisma, and it’s hard, today, to remember just how magnetic his picture personality was in the ’80s. But in 1987, he married Mimi Rogers and became a practicing Scientologist; two years later, he met Nicole Kidman on the set of Days of Thunder, divorced Rogers, and married Kidman. For the golden boy of Hollywood, it all could’ve been very scandalous—or fascinating, given the proper writer.

But Cruise had Pat Kingsley. As head of PMK, Kingsley’s publicity firm was widely regarded as the most powerful in Hollywood. Throughout the ’80s and into the ’90s, she ruled press access to Cruise with an iron hand. As Anne Thompson outlines in the Hollywood Reporter:

Anyone who has ever dealt with Kingsley knows that going up against her takes guts and the full backing of your organization. That’s because she’s willing to use her entire arsenal to protect her most powerful clients. With the bat of an eyelash, she’d withdraw the cooperation of her agency’s other stars, refuse to cooperate on other stories or ban a publication from getting another star interview… Kingsley controlled the select magazine covers Cruise would do for each picture, the friendly interviewers he was most comfortable with, the photographers who shot him to look his best. Knowing that he didn’t have much to say, she controlled his image, preserving his mystique as a movie star. Her PR philosophy has always been, “Less is more.” Keep the fans guessing. Hold the star in abeyance. Keep everyone lining up clamoring for more.

In other words, Kingsley masterfully protected Cruise from questions and queries concerning Scientology, his sex life, and his marriage and divorce, yet managed to make his brand distinctive, internationally recognizable, and unquestionably valuable. She managed the type, tone, and volume of gossip that would circulate about Cruise, bolstering the specific star image set up by his iconic roles.

The phalanx of Cruise, Ovitz, and Kingsley represented a return, albeit in slightly different form, to the publicity apparatus of classic Hollywood. Cruise was not contracted and controlled by a single studio; rather, he amassed his own mini-studio around him. The result was just as airtight and effective as if he were at MGM in the ’30s. It would follow, then, that the profile would return to the level of banality that attended the same level of management.

In August 1988, for example, Cruise was ascendant: fresh off the success of Top Gun and Cocktail, nearly finished with the filming of Rain Man, and already signed to “texture” his image with a risky performance in Born on the Fourth of July. The cover of Rolling Stone promised a “straight-up talk” with the star of Cocktail, and the beginning of the profile augurs well. Cruise, it seems, has just called the profile’s author, Lynn Hirschberg, on the phone, with a pointed request: he’d like to change his description of Top Gun from “surreal” to “real.”

This attention to detail, according to Hirschberg, is “typical Cruise,” who’s “more than a little interested in controlling the situation.” We learn that Cruise requested that the interview take place in Hirschberg’s hotel room, not his own; Cruise purportedly wanted to “concentrate,” but Hirschberg knew better: his hotel room might shed light on his personality, and Cruise is “very careful about what he reveals, whom he decides to trust, and what his next career move will be.”

It’s a provocative way to start a profile, with the implicit suggestion that everything that follows is highly mediated and carefully calculated. But it’s just a hook—another way for the reader to feel that they know the “real” Cruise, who, in this case, is “really” conscious of his image and career. The lead paragraphs segues into a boilerplate description of Cruise’s rise to fame—parents, first roles, struggle—leading to what amounts to the thesis of the profile:

A combination of shrewdness and all-American boyishness is one of the reasons that Cruise has been so successful in his career. Yet there is an edge: Cruise is serious about his goals. He’s like a boy scout—thoughtful and brave and loyal and all the rest—but his honest-to-gosh good-guyness is mixed with steely determination. And that’s what audiences find so compelling. “He believes anything is possible,” says Top Gun coproducer Don Simpson. “That’s the key to Tom Cruise.”

It reads like the description of a superhero—a veritable Top Gun—and it’s absolutely on point with the overarching message of Cruise’s image. Forget what you just read about Cruise’s micromanagement, his calculation bordering on coldness—this is the real Cruise. It’s an image wholly built on hollow platitudes, but it towered over all other celebrity images.

Cruise and Kingsley weren’t the only ones playing the game this way; they simply set the bar. Profiles of the biggest stars of the 1980s and ’90s—Sylvester Stallone, Julia Roberts, Harrison Ford, Bruce Willis, Demi Moore, Tom Hanks, even Madonna—were tame and on message, especially compared to the profiles from just twenty years before. The reboot of Vanity Fair in 1983 facilitated the reversion, filling its pages and, especially, its cover, with the promise of titillation—Moore in a painted-on tuxedo; Stallone naked and posed as Rodin’s Thinker; Madonna topless in a pool floatie—only to return to well-worn platitudes and well-tailored quasi-confessions inside the magazine. We’ve developed a modicum of nostalgia for this period in celebrity history, pre–digital culture, pre–reality television, when stars still seemed to be something larger than life. It’s no coincidence that that feeling—a feeling often used to describe the relationship between fans and stars from the classic era—was also the period of solid, highly crafted, and perfectly boring celebrity profiles.

*

In a Columbia Journalism Review piece from the fall of 2012, Douglas McCollam claims that Capote’s profile of Brando heralded the arrival of not only the New Journalism but of today’s ubiquitous celebrity culture. “With its profusion of intimate details, confessional tone, and novelistic observation of Brando’s character,” McCollam writes, “the story marked a clear evolution of celebrity journalism and heralded the arrival of the invasive, full-immersion pop culture of today.”

In many ways, McCollum is correct: the no-holds-barred intimacy and the “real-life” confessions do indeed characterize today’s reality celebrity culture. Without full access to these new exemplars of the pseudo-celebrity—the good and the bad, the despicable and the redeemable—they would lack the melodrama that renders Hollywood stars compelling. Hollywood stars embody superlatives—the most beautiful, the most charismatic, the most hilarious. Publicity grants them “normal” and domestic characteristics to render them just accessible enough to avoid jealousy. Reality-TV stars, by contrast, are men and women who are, quite literally, just like us. Their ability to commodify their “normal” lives (pregnancies, relationships, breakups), both on “live” television and in the tabloid press, is what sustains their careers after the end of the season. They’re famous for being themselves; without unadulterated access to that “being,” their fame disappears.

But that’s just one swing of the pendulum following Capote’s watershed profile. Now the “tell-alls” and constant intimacy are, in fact, only simulacrums of intimacy—postmodern echoes of the profiles that typified the silent and classic Hollywood era. They may spend more time with the star, they may offer “real-life” documentation, they may include streaming video and seemingly irrefutable evidence of the reality celebrity’s true self. But they’re just as highly manipulated, albeit far more digitally accessible, as any fan-magazine profile from the ’20s. Their hollowness stems from the disparity between what’s ostensibly promised and what’s delivered: like The Hills, we have round-the-clock footage that, ironically, reveals nothing save the high production values of the channel on which it’s aired. This type of coverage feeds the appetites whetted by the illuminating profiles ushered in by the New Journalism, but it’s hollow and, ultimately, wholly unsatisfying. Which, ironically, is why so many of us can’t stop watching it.

The profiles of the New Journalism were electrifying, but they made no small amount of the American public uncomfortable—the selfsame American public that fuels the entertainment industry. And so, as the industry continues to panic, retreat, and cling to old models of production, we’ll suffer, mindlessly, harmlessly, stultifyingly, through the banal celebrity profile, tricking ourselves, as seems to be a common theme in contemporary culture, into believing that the pretty, the polished, and the easily swallowed actually tastes like something real, or nourishing, or good.