The last published novel of Gilbert Sorrentino—his twentieth, though the math is complicated by his constant rejiggering of what, exactly, constitutes a novel—initially appeared to be A Strange Commonplace, published in 2006, shortly before his death. Nonetheless, the following year, the online magazine Golden Handcuffs Review ran the equivalent of eight or ten pages from a subsequent longer work. The author’s son Christopher (himself a novelist) arranged for the publication of this longer work with his father’s last publisher, Coffee House Press (to be released next month), and added an opening note, sharp yet moving, which claims that the book was finished, its final adjustments made by his father’s hand.

The Abyss of Human Illusion is an assemblage of prose shards, none longer than four or five paragraphs, each refracting some small light into another corner of Sorrentino’s imaginative homeland, the beaten-down working class of mid-twentieth-century Brooklyn. Yet Abyss resists easy characterization as urban realism, since each entry closes with a “commentary,” much of which is quite funny, masterfully spinning through rhetoric high and low: “He was no better, no cleverer, no more insightful than any shuffling old bastard in the street, absurdly bundled against the slightest breeze.” Gallows humor pervades the whole; an old writer, unnamed, laments the fraudulence of his calling. Like everyone here, he’s “left a lot of wreckage behind.”

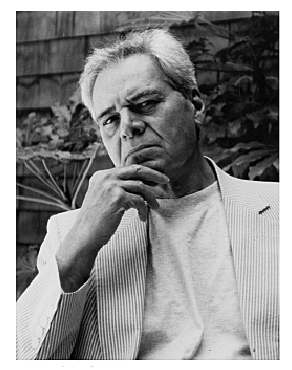

Gilbert Sorrentino dedicated a career to an assault on expectation. In some cases he attacked head-on: few other serious authors savaged, with such ferocious energy, the publishing industry. As early as 1971, referring to mid-Manhattan’s Powers That Be in Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things, he sneered, “You could die laughing,” and he went on dying in print for another thirty-five years. Nor was he reluctant to bite the other hand that fed him. Though he taught for twenty years at Stanford, his “Gala Cocktail Party” from Blue Pastoral (1983) was a brilliant skewering of academy phoniness.

In an essay on William Carlos Williams—his enduring inspiration—Sorrentino insists, “America eats her artists alive.” That is, the culture celebrates creative spirits who produce “trash.” “Writing is most admired when it is decorously resting… the more comatose, the more static a mirror image of ‘reality’ the better.” So the great majority of his countrymen “employ language and techniques inadequate” to the times, creating drama via hand-me-down emotional signals, interactions across “a sea of manners.” In the work of John Updike, to name one of his bêtes noires, catharsis was nothing but a papier maché of chewed-up and regurgitated convention: trash. Such contrariness...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in