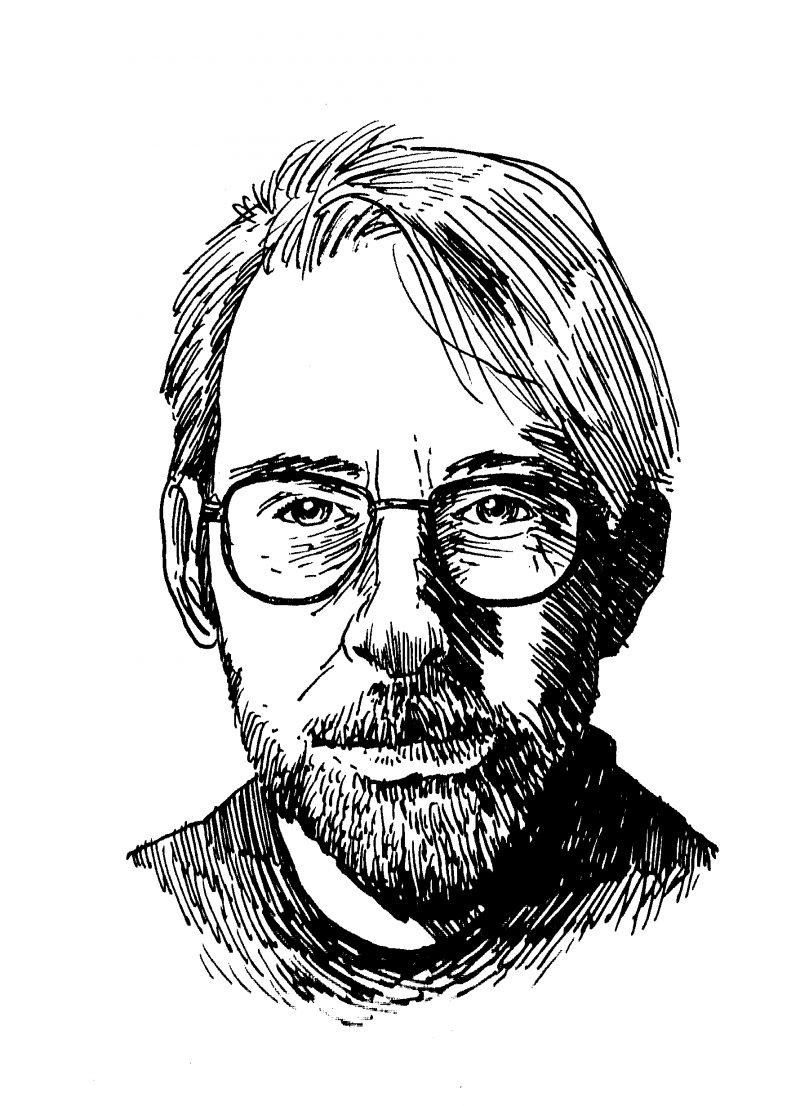

Walter Murch is a film editor, sound designer, director, and amateur astronomer. His pioneering sound and picture work includes the films THX 1138, The Godfather, The Conversation, Apocalypse Now, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, The English Patient, the restored Touch of Evil, and Cold Mountain, among many others. He has been nominated nine times for an Academy Award and has won three Oscars. He is the author of In the Blink of an Eye, a book about the craft of film editing, and is the subject of two books: The Conversations by Michael Ondaatje and Behind the Seen by Charles Koppelman. He most recently directed an episode of the animated series Star Wars: The Clone Wars for Lucasfilm, and is currently editing the film Hemingway & Gellhorn, directed by Philip Kaufman.

David Thomson attended the London School of Film Technique. He has served on the selection committee for the New York Film Festival, and he is on the advisory board of the Telluride Film Festival. He has contributed regularly over the years to the Independent and the London Guardian, and to Film Comment and the New Republic. He is the author of many books, including Showman: The Life of David O. Selznick; Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles; The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood; and The New Biographical Dictionary of Film (now in its fifth edition); as well as Suspects, Warren Beatty and Desert Eyes: A Life and a Story, and Nicole Kidman, all of which are so hard to classify that they need to be read. Most recently, he wrote and delivered the BBC radio series Life at 24 Frames a Second.

This conversation took place one evening in December 2010 at David Thomson’s home in San Francisco.

DAVID THOMSON: You said a little while ago that you were unhappy about the world as it is at the moment, and god knows there is reason for that. Do you feel that American art culture, what have you, media, is organized in a way that can express that pain and that problem? Or do you feel increasingly that one of the most grievous problems is that we no longer have the forum and the voice where this distress can be expressed?

WALTER MURCH: Well, it certainly is expressed, covertly, anyway, in films like Roland Emmerich’s disaster operas: Independence Day, The Day After Tomorrow, 2012....

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in