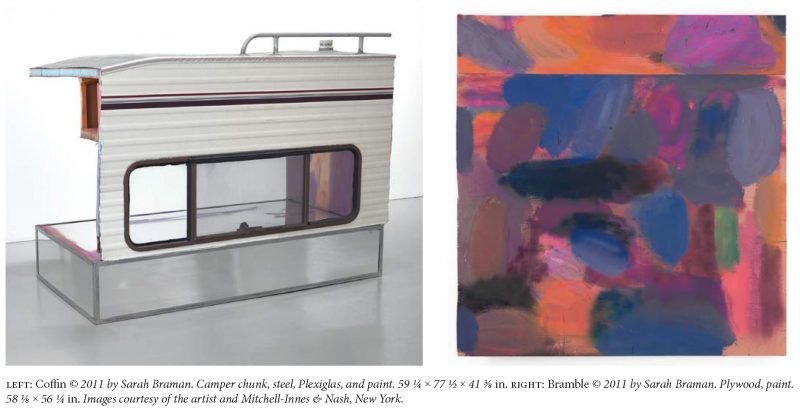

In 2011, Sarah Braman sectioned an old camper trailer and scattered its pieces throughout a gallery like flotsam. In some places, she added gentle accents of lavender spray paint; in others, she affixed deep-hued Plexiglas cubes like curiously empty fish tanks. Some of the camper’s chunks were tipped off their natural axes and some of its innards—a mattress, a window—were affixed to the walls like confident, stately paintings, as if they were always meant to be art.

Braman has a penchant for seeing the most common of objects—desks, cushions, file cabinets, tents—through the eye of an outsider. She extracts an unremarkable portion of the world, makes a few quick alterations, and then presents something fresh and unexpected. It’s a sleight-of-hand move that characterizes great assemblage, and Braman does it using a painter’s transformative touch. With her own vocabulary of marks and materials, she gives motion to her sculptures, sending them tumbling through the world, accreting color and detritus as they go. If you look at these objects with art in mind, they suggest an idiosyncratic lineage of artists—Odilon Redon, Robert Rauschenberg, John McCracken, Rachel Harrison—but the work itself carries an attitude of casual disinterest toward the -isms of fine art.

Braman lives with her family outside of Amherst, Massachusetts, and, occasionally, in the Chinatown neighborhood of Manhattan, a few blocks away from CANADA, a gallery she co-runs with her husband, Phil Grauer; Suzanne Butler; and the artist Wallace Whitney. Since 2002, the space has developed a singular, adventurous position in contemporary art, exhibiting a family of artists (Xylor Jane, Brian Belott, Michael Mahalchick, Katherine Bernhardt, Michael Williams) who are both visually cohesive and consistently unpredictable.

I spoke to Braman at my apartment while Grauer tended to their newborn in the next room. A few weeks later I attended the gallery’s annual summer sleepover at a Quaker retreat center in rural Massachusetts, where Braman and Grauer had gathered several dozen artists and friends to play badminton, strum instruments, sing, make piles of drawings, and spend a nice, long weekend forgetting about the buzzing, urban art world 150 miles down the road.

—Ross Simonini

I. THAT SPINNING PLACE

THE BELIEVER: How do you find the objects you use in your work?

SARAH BRAMAN: It tends to start with the stuff that’s closest. If I wind up getting hooked into something, then I might go out looking for it. I’ll get a hankering for something. But a lot of the time it starts with furniture that’s around the house, or stuff I see when I’m driving around that’s on the side of the road. We live in Amherst, Massachusetts, so in the early spring when the students move out there’s always a bunch of junk along the road when they’re leaving their dorms and apartments.

BLVR: And what about the camper?

SB: I wanted one that fit into a truck so I didn’t have to deal with a chassis or anything like that. The shape’s kind of cool. It has more structure to it. It wasn’t that hard to find, really, but, you know, to find one that’s not too rusted and cheap enough and they could deliver it…

BLVR: Do you choose objects for purely visual reasons?

SB: It’s definitely more than the form. I probably weed out through a formal lens, too, but it’s also the psychic makeup of whatever it is, and sometimes the narrative makeup. There are complicated layers with found objects that I enjoy.

BLVR: What do you mean by “narrative”?

SB: A narrative or, at other times, a loose presence. The spirit of an object. The humanity of these things and the lived parts of these things, I think, can pile up to some mound of psychological being.

BLVR: Are new, store-bought objects less interesting to you?

SB: Not necessarily. I tend not to have a ton of no-nevers. When I was using camping tents, I’d get those new.

BLVR: What you were just describing as psychological buildup—does that connect to mark-making and painting for you?

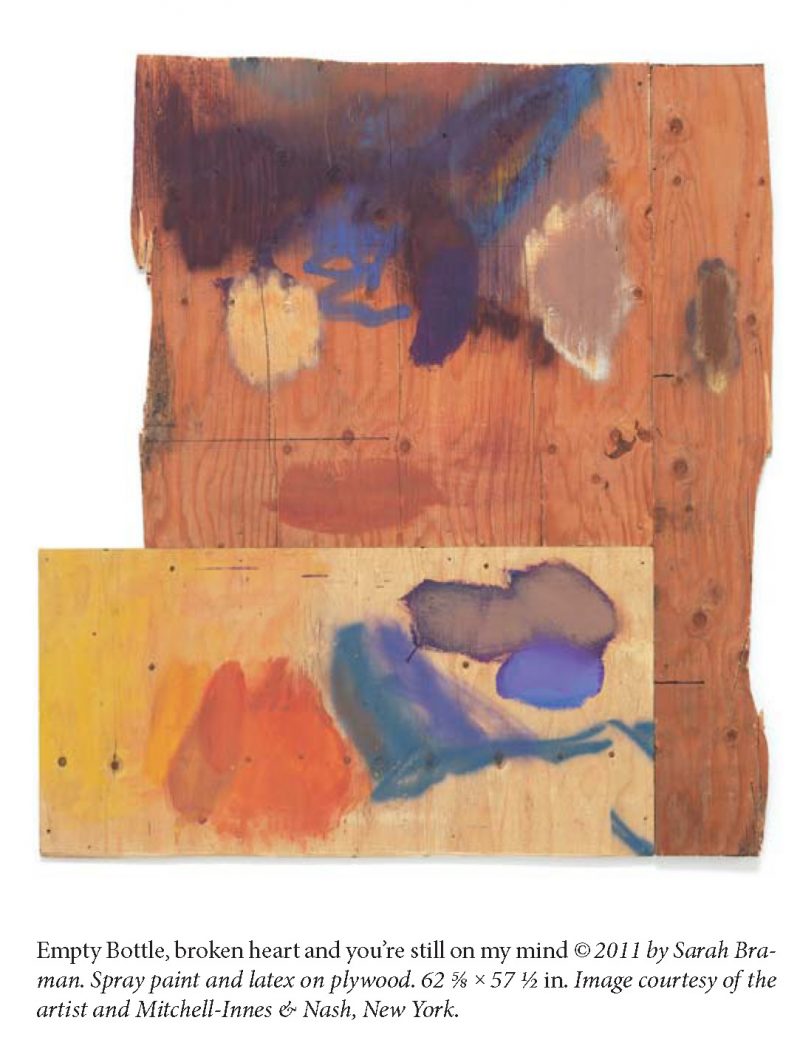

SB: Yeah, I think so. That’s the part there isn’t words for. You can describe a desk: it’s kind of gray and it’s got this flat top and it got cut in half and now it’s on its side. But then the mark-making is the place where I can make some sort of expression of what I can’t describe in verbal language. I have a drive to do that.

BLVR: Do you think that the sculptural maneuvers are not expressive in the same way?

SB: The movement, the form—all that stuff—the positioning, the formal arrangement and everything. I think it’s all working together like that.

BLVR: How many options are you cycling through for these sculptures?

SB: Sometimes it comes together pretty quick and other times things tumble around for a while before they get settled.

BLVR: Things will sit around for years?

SB: Yeah. There’s a lot of things growing slowly. And then the wall, the panel painting pieces, a lot of times I’ll be using them just to mix paint. They’ll be on the floor. They’ll be used under the circular saw, on the sawhorses. I enjoy having a lot of stuff around on the periphery at different stages of life.

BLVR: Are you interested in transforming objects from their original state?

SB: It’s nice when I don’t know what I’m looking at, when I get this feeling like the rug is being pulled out from underneath me and I just don’t know what is going on. To get to that spinning place. I know I enjoy those experiences in all areas of being alive and human. And it just so happens that one of the ways I get there in the studio is by getting into that in-between state where the objects flux back and forth.

BLVR: Between the original thing and something else?

SB: Yeah, exactly. I want to make an object just as good as any other. To be able to have an experience that’s somehow puzzling or create something for people to have an experience with. It’s almost like what the particulars of the experience are is not so important. It was a camper before and that was awesome, and now it’s this other thing and hopefully it can be as good as the thing it came from. Good is a stupid word: engaging. And the camper, that’s hard because people have pretty awesome experiences with the original object, so I’m probably not going to get better than that.

II. THE CHATTER UPSTAIRS

BLVR: Do you ever use these pieces at home as furniture?

SB: Yeah, the house is full of stuff that I guess is halfway between. We’re trying to make a picnic table right now, a hexagon. I worked at home for so long. And I think that having kids and being home-centered, it joined domestic life. It’s bound to happen because that’s where I spend a lot of time and energy.

BLVR: You were working in your living room, but you’re now working in more of a separate studio space.

SB: Yeah, I’ve been renting studios for a few years now.

BLVR: Do you feel that’s connected at all with being able to show more, sell more?

SB: The economy.

BLVR: Yeah.

SB: It’s partly a choice that I made happen, and the first studio I moved into was a little bigger than this [small] room. That was a conscious decision, because I thought I’d need to be able to get a little bit of distance and have a space where I could make stuff and be able to look at it a little bit longer and not worry about it being on the porch and getting rained on or having the neighbors watching me.

BLVR: I’ve heard you say that, for some shows, you make all the work right in the gallery during installation. In those cases, were any of the decisions planned out or was everything improvised?

SB: Occasionally there’d be decisions made beforehand, but most of the time I was either gathering stuff from around the gallery or bringing a bunch of junk that really had not been considered in any way as how it would go together. And then just bringing the tools and paint and a feeling.

BLVR: Did that end up creating a certain kind of work process for you?

SB: It was definitely, yeah, under the gun. I think part of that also is with the kids you don’t have the same kind of time. So if you have twelve hours where the kids are asleep or accounted for, those twelve hours can expand. And I also like the challenge of that. I like the fear. There’s a part of me that enjoys that terror of: this isn’t going to work at all. And then finding some way, digging some way out.

BLVR: A stripe of paint in your work looks like a captured moment.

SB: There’s just no room or time for thought. The getting away from the brain is helpful. My brain can be pretty annoying most of the time, so it’s nice when I get a really big break from the chatter upstairs. I mean, the brain is good and there’s lots of stuff I need to use it for, but I’m not sure the studio is the best place for it.

BLVR: Does the art you enjoy looking at also allow you to escape your brain?

SB: Yeah, when I can look at something and get an experience that can’t be described by my brain, it gives me this chance to go to some other place. That’s the best. To get led someplace that’s like: I don’t know where the fuck I am. I don’t know how I got there. I don’t know what’s going on. But whatever artist made this thing drag me to this new experience that I have no idea about, that’s awesome. I think that there are people like critics and writers who are good at taking that experience apart and actually describing how it’s functioning and what the operatives are. I can enjoy reading that stuff, but I’m not going to be able to be the person who’s going to give you directions, like a road map. For me, the object is the hope of that kind of getting out—an out-of-body experience. I find that such a gift, if I can be brought there by somebody or something. Art can do that.

BLVR: Do you read reviews of your shows?

SB: I read everything. Anybody that’s going to take the time to look at and write about whatever I put into this world, I’ll look at for sure.

BLVR: Have you had that baffling feeling through a photographic reproduction?

SB: Yeah, for sure. I’ve looked at pictures of sculptures in books that I’ve never seen in person before, and it’s not the same, but I don’t think it’s worthless, either. And then sometimes seeing so many images together can give a different kind of perspective, like a book of twenty images of different stuff from different years. That’s pretty cool. There was a John Chamberlain book I remember that I had checked out in college. It was, you know, all his work up until then, like 1995. That book made a huge impact on me, and I hadn’t seen very many of his pieces in person at all. But you’re seeing all these sculptures pile up on each other in kind of a longer view over time and, yeah, that was powerful.

BLVR: How do you feel about the trajectory of showing your work and having people respond to it? Have you felt satisfied with that process?

SB: I’m not sure exactly. I mean, it feels like making art is a group activity and a very private activity at the same time.

I guess I can say that both the private part of that and the group part of that have been really rewarding. The private part—obviously, it’s mine. I get to do what I want to do and I don’t have to give a shit. That arena is mine and I can pull stuff out of it into the public or not. And all the freedom of feeling that that privacy offers has been really rewarding, and then the feeling of sharing that with peers and getting to look at their stuff, too, and growing together. That sounds corny. And it’s not like I’m in everybody’s studio all the time and they’re in mine. People hardly ever come to my studio. But the connections that are there feel real and important.

BLVR: But the reception of your work hasn’t disappointed you.

SB: It’s not like everybody likes everything. They can think my stuff is stupid and I can go, Yeah, well, fart you, try this one on, whatever—or be more gracious. All of those things are fine. I’ve had my feelings hurt, but I don’t necessarily think that’s a bad or a good thing. I don’t mind a little bit of friction. I can be kind of fighty. I think there are camps in art just like there are in anything else, like sports or politics or ways of farming or shoemaking. It’s not like I pay attention to that all the time, but I am sensitized to that particularly through work in the gallery, and I’m happy to take a position if need be. I don’t mind being a goon.

BLVR: Do you think your gallery has developed a particular camp?

SB: I guess it’s impossible not to. It’s just what happens.

BLVR: Most galleries develop a camp.

SB: Yeah. Maybe it’s a little stronger because we’re—I don’t know, more personally connected than some other galleries are.

BLVR: Because you’re an artist?

SB: Yeah.

BLVR: How do you think that affects the gallery?

SB: I think there’s tons of conflict but I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing. Our gallery is just this fucked-up entity that never should have survived, because no one really knew what they were doing. We need to act in a professional manner in certain circumstances to maintain a place in the arena, but we’re not very good at it. It’s, um, Phil should be here. The gallery is really his idea. It’s really his bad idea [laughs]. Yeah, it’s his energy that started the thing, and then quite quickly he invited the people. He didn’t want to do it alone. He invited a bunch of people to participate. People fell to the wayside and then there was a core of people that were left running the thing.

III. STUPID ZEN

BLVR: Some of your work hangs on a wall and some of it sits on the floor. How do you decide?

SB: I guess if it’s freestanding it goes on the floor.

BLVR: It’s that simple.

SB: Yeah, any of the flat works—I make them for the wall. To me they feel windowy. They’re windows or doors to the outside, to other dimensions.

BLVR: You’ve used the word other a few times now. Is otherness on your mind often?

SB: Uh, yes. [Laughter] Yeah, definitely. It’s on my mind a lot. I don’t, um, I haven’t done, like, extensive reading on any particular religions or spirituality. But I am open to learning about it and thinking about it and practicing.

BLVR: Do you mean meditation?

SB: Yeah, primarily meditation and prayer and different sorts of things, like taking walks in the woods. Stuff that can be helpful to just, yeah, get beyond my own self, which is usually in the way of most good stuff.

BLVR: That’s where the ideas come from?

SB: Yeah, it’s definitely all tied together. It’s all kind of the same: chatting with you or the baby or the teenagers or gardening. It’s hard because I feel like it gets into super corny territory, but—I mean, what else is there? I guess there’s other stuff, from swimming to sex to reading a book. It’s like stupid Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. There’s a whole pop phenomenon around it—but maybe it’s for a reason? I think a lot of people—or at least I’ve experienced this with some people I know—folks find some relief in getting out of the self somehow. For me, it’s a completely losing battle, but that’s kind of irrelevant. Boy, this is going to sound… Phil is just going to be reading this interview over the toilet, puking.

BLVR: When you were growing up, your mom built your house by hand. And I wonder if that sort of experience, growing up with someone who is physically making things all the time—even the structure that you’re living in—had a direct effect on the kind of things that you make.

SB: I would say yes, that was definitely liberating. Watching her build a house just made it seem like you could build anything. You want something, you build it. I remember the house was plywood first and then tar paper. I remember when it was just the sheeting, thinking, Why wouldn’t you just paint huge flowers on this house? Why wouldn’t you do that? I knew that Mom was in charge, and I knew I wasn’t going to be making that decision, but I couldn’t understand why the person in charge wouldn’t just be painting all over the house.

BLVR: Is that what you do now?

SB: No, I don’t paint all over my house.

BLVR: Why not?

SB: I don’t know. Well, we just bought a house, so I never could before, because I never owned one. The house is really beautiful, the way they built it. It’s kind of perfect. There’s no need.

BLVR: You said sculptures kind of came out of that. When was that?

SB: Oh, I don’t know. I think I was, like, five when she built the house.

BLVR: You were making sculptural things at that point?

SB: Yeah, well, I made a bunch of art as a kid—more drawing—but it was in the woods so there was a lot of stick art and pinecones. I wouldn’t call it sculpture, but a lot of messing around with stuff.

BLVR: Is your work especially informed by nature?

SB: I do experience it that way a lot, actually; especially installing or making the studio feels like fields and mountains and rocks. It’s just so physical. Like the surface of the earth. Like a large mountain face when it gets cut open. All that stuff. That physicality is hard to push aside, and I don’t see why I’d want to.