I first met Ryan McGinley at the restaurant my husband and I own in Cherry Valley, New York. He and his boyfriend spent a few days up here visiting the writer and artist Jack Walls. I wanted to meet Ryan: I love his early, gritty New York photographs of dazed but joyful street kids riding bikes, sleeping in, having sex, and writing graffiti, and his more recent pastoral photographs of young people at play, naked and laughing. I also love his gorgeous photo series of fans in ecstasy at Morrissey concerts. But I didn’t know what to expect; it’s hard not to imagine the worst of someone with the kind of early success Ryan has had. He had a solo show at the Whitney at the age of twenty-four; he has had glowing reviews and features in the New York Times and the New Yorker; he had a show at MoMA P.S. 1; and this year the International Center of Photography named him Young Photographer of the Year. Ryan, as it turns out, has the grace and manners of a choirboy. He has a striking, delicate, Man-Who-Fell-to-Earth glamour. I thought we had an easy rapport—but I think a lot of people feel that way about Ryan. I think it is part of what makes him successful.

I interviewed Ryan in March 2007 at his studio on the Lower East Side.

—Dana Spiotta

I. “SKATEBOARDING IS A LOT LIKE PHOTOGRAPHY BECAUSE SKATEBOARDING IS ABOUT MAKING SOMETHING OUT OF NOTHING.”

THE BELIEVER: How did skateboarding help you become an artist?

RYAN McGINLEY: When I was younger I started coming into the city to skateboard on my own—probably when I was about twelve years old. We would skate next to and underneath the Brooklyn Bridge. The area we skated was called the Brooklyn Banks and we would skateboard most days after school. When it got darker, we would slowly make our way up to Astor Place. It was a place all the skaters gathered at night. On the way there was this gallery on Ludlow Street called the Alleged Gallery. This gallery showed a lot of artists—a lot of skateboarders who made art. My friend’s sister was an intern there—she used to sweep up the gallery—and I remember going in and looking at the show and thinking, Wow! This is really cool. I can’t believe that these skateboarders are making art like this. The first show I saw was a Mark Gonzales exhibition. I started going to the openings every month at that gallery and they showed lots of great people. Spike Jonze was really involved and Harmony Korine was really involved and Mike Mills was really involved and these were the people I really looked up to.

BLVR: And it inspired you to do something.

RM: Yeah, I started making my own work. My introduction to photography was making skateboard videos. I got a video camera when I was in high school and I would videotape all of my friends skateboarding. But then I realized that I wasn’t interested in the actual skateboarding. I was more interested in what happened in between, you know—sort of behind the scenes, hanging out, and people’s personalities—and that’s what got me interested in documenting people. And then eventually that became photography. But initially it was making these videos. There was this one video in particular that Spike Jonze made called Video Days. There were elements in it that were far and beyond what a skateboard video should be—it really became like an art piece. Watching stuff like that made me want to do my own videos. Mike Mills was making really cool videos too. He did this piece that I always think about called Hair, Shoes, Love, and Honesty. He cast all these people off the street, from old to young— just people you would see on a bus or in a subway car—and he asked them all these questions about what they thought about their hair, and what they thought about the other people’s hair, what they thought about honesty, what they thought about love, what they thought about shoes, and it was done very stylistically. It had different color backgrounds and it was just cropped at their chests. When I saw that video, I was very young and it really inspired me. I mean, I’ve been going to museums my whole life, to the Museum of Modern Art on school trips and to the Met and to the Whitney. But having that gallery made it seem tangible. When you go and look in a museum, it’s as though it’s not real. Most of the artists are dead and it’s already part of history.

BLVR: Right.

RM: It just seems out of reach, but at this gallery, you could meet the artists. They were nice to me. I looked up to them.

BLVR: And you related to the subject matter—skateboarding and street culture.

RM: Yeah. When I talk about skateboarding, it’s really tough for me because it was such a big part of my life. But when you talk about skateboarding and art—there are so many bad connotations within that…. The people that I am telling you about are the people that took the idea of skateboarding and the lifestyle and made something else out of it. But there are a lot of artists that make “skateboard art,” which is bad, like really bad. But what I learned from skateboarding was about people. I am from a predominantly white suburban town, and if I didn’t find skateboarding, I wouldn’t be the person I am today. It got me out of the town I lived in. It made me meet kids who were different ages, different races, different economic backgrounds, from all over the world, and it didn’t matter—none of it mattered. All that mattered was skating together. And it brings you to all these different places all over the city—you will be up in Midtown skateboarding and you are exposed to all these businessmen and you might go to the ghetto in Brooklyn and then you go to the Village and all the eccentric people on the street, the artists, the homosexuals—so many cultures mixed together. You’re always on the street. And then, for me, skateboarding is a lot like photography because skateboarding is about making something out of nothing. You’re using the urban landscape as a playground and you’re making ideas for doing skateboard tricks—using a handrail or some yellow curb on the sidewalk—and photography is about the same thing for me. It’s about starting out with practically nothing. You have to sort of create these scenarios to shoot, these ideas to work, and you have to use the world as the backdrop for your photograph.

BLVR: Let’s talk about the first book of photographs, the one you did yourself and sent out. It’s a sort of legendary D.I.Y. thing that you sent this handmade book out to artists and editors and it is how you got discovered, right?

RM: Yeah.

BLVR: So you really put yourself out there. Did you just look at the photographs you had been taking and say, This works, I’m going to do something with this?

RM: I mean, it wasn’t a decisive moment like that, but I was making photographs, and since I was studying graphic design, I was very familiar with computers. I wasn’t knowledgeable enough to use the darkroom, but it was right around the time when digital negative scanners came out—it was the late ’90s—and they were new and no one really knew about them. I bought one and it was basically like a darkroom on my desktop. It was easy for me to do desktop publishing since I was doing that for my graphic design assignments. I was able to reproduce books and I knew how to make them. I had taken a bookbinding course.

BLVR: So it looked pretty good.

RM: It was a really legit-looking book. It was definitely a really nice handmade book and then I just went crazy with it and made so many of them. Originally I made them to give them to my friends and then I gave one to Jack Walls and then Jack showed it to one of his friends whose father owned the 420 West Broadway building in SoHo. Four twenty West Broadway was a legendary art building. Mary Boone’s gallery was in it, Leo Castelli was in it, Sonnabend was in it. There were amazing shows that had happened there from the late ’60s onward but it was at the end of 1999 and all the galleries had moved to Chelsea. Jack knew the owner of this building and they were going to tear down the bottom floor to become a DKNY store. So it was open and Jack said, “You should do a show here because nothing is going on.” So I asked the guy who owned it and he said, “Yeah, do whatever you want with it.” I did this do-it-yourself show. It was a really, really big space and I went to the color darkroom and asked some people how to make photographs and I just thought, OK, it’s such a big space, I have to make really big, large-scale photographs. I made sixty of them, postersize photographs.

BLVR: And were they the photographs that were in the book?

RM: Yes, and then for the show, since I had been making these books anyway to give to my friends, I de cided to make a book for the show. The show was called The Kids Are Alright and I made a hundred of these books. The morning before the show I had a production line of friends helping me assemble the last of them, right up until the last minute. At the show maybe forty of them sold—we sold them for twentyfive dollars. Then I had all these books left over so I decided to send them out to magazines I liked. And to artists I admired. I sent it to the artist’s gallery and said “for this person.”

BLVR: Which artists?

RM: Oh, the usual suspects, like Nan Goldin and Wolfgang Tillmans. I had already known Larry Clark and gave him a book.

BLVR: I love the title, The Kids Are Alright. Obviously that’s a Who song, but was it also meant to be an answer to Larry Clark’s Kids in some ways?

RM: No, not at all.

BLVR: OK.

RM: That’s actually the first time that anyone’s ever said that. That’s quite interesting.

BLVR: The film Kids is so bleak and I thought maybe you were saying, actually the kids are alright, you know, we’re doing fine.

RM: No, I love that, though.

BLVR: You just like the Who song.

RM: Yeah, because I was raised by my older brothers and sisters, I was really into the Who when I was growing up.

BLVR: Did you get a big response?

RM: There was a really amazing response to the book. It freaked me out how many people called me back. Index magazine was the first magazine that called me. The guy who owned Index said, “I really like your book and I really want you to photograph for our magazine.” That was a big deal for me because the roster of photographers for Index was one of the best in the world at that time: Jürgen Teller, Bruce LaBruce, Wolfgang Tillmans, Terry Richardson, Richard Kern, just to name a few.

BLVR: They didn’t really know who you were, right?

RM: They didn’t know who I was at all, and then they asked if I could fly to Berlin tomorrow to photograph somebody. And I was freaked out, but I said yes, of course.

BLVR: Your life had changed.

II. PHOTO SHOOTS AS HAPPENINGS

BLVR: After The Kids Are Alright, you stopped taking pictures of the scene you found around you. You started doing these photography road trips. Maybe you could talk a little about the road trip pictures—they are composed, but they are also spontaneous.

RM: The idea for the road trip came about because my friend Mike Mills was making a film called Thumbsucker and he invited me to the set to make photographs behind the scenes. I went to Oregon for about a week and a half and photographed on his set. When I was making those photographs, I got really inspired by watching him work and seeing how a movie was made. It gave me this idea of having locations and doing numerous shoots during the day—taking people and going away with them, taking them away from their normal environment and putting them into this world that doesn’t exist except on the road: the reality of my photographs or the fantasy of my photographs. I de cided I really needed to do this, to plan a long road trip. We did the trip and it was almost three months that we were on the road in the summer of 2005. A lot of things were planned, but a lot of things just happened, too. You never know where the road might bring you.

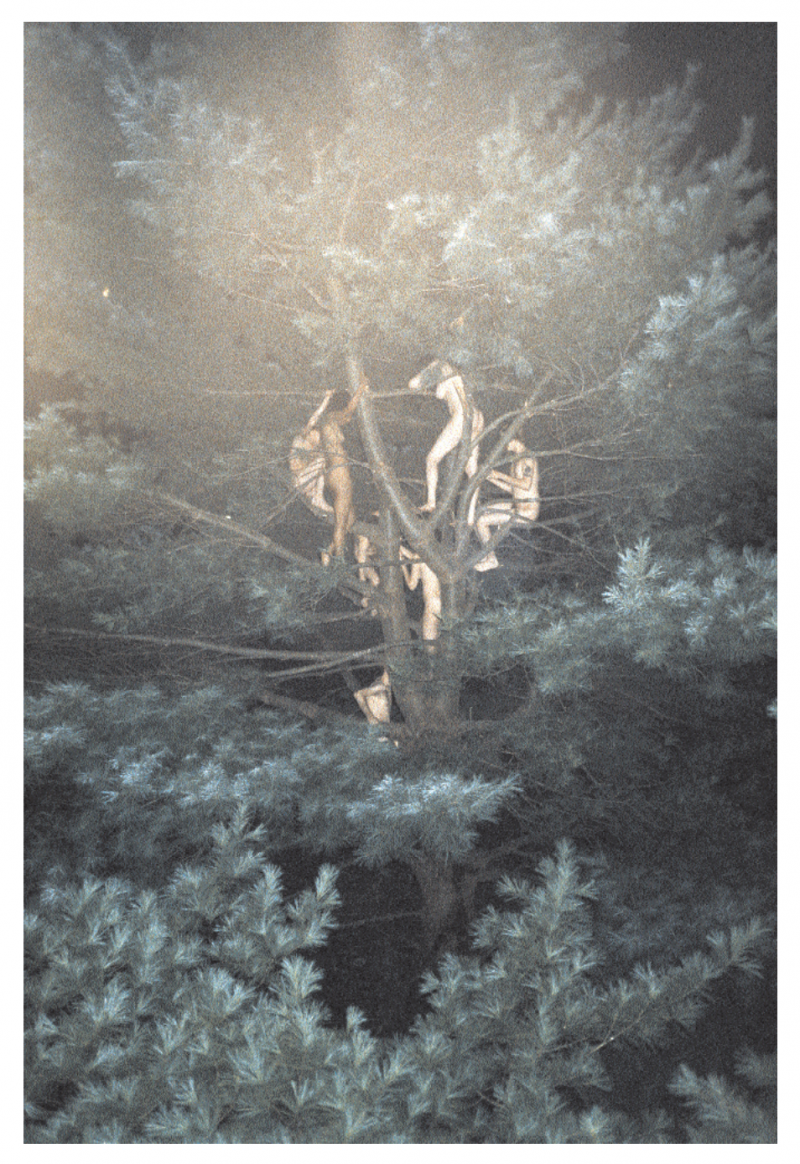

BLVR: Give me a specific—let’s say the photographs of all the people in the tree, Tree #3. How did that happen, for example?

RM: I just wanted to make a picture of a bunch of people naked in a tree. I had done a shoot with somebody—I do these shoots at nighttime where we walk around and it’s completely dark. I shoot just using the flash to guide us. We were just walking around and one of my friends went up in the tree. I thought, Well, it’s not that interesting with one person in a tree, but if there was a group of around ten people in a tree, that would be beautiful. So I spent all day the next day clearing out the branches in that tree. I found the perfect tree and also I found a tree that was next to it so I could shoot from one tree to the other. I really wanted the people up high in the trees so there wouldn’t be any evidence of the ground at all. I spent all day clearing it out. Then we kind of did the buddy system, everyone held hands as we went out to the tree because it was in the middle of this field and it was really dark at night. Then everyone climbed the tree naked. I make a lot of photos when I shoot. I have an idea of what I want, but to make the kind of photographs that I do, I can’t pose people. I can create an environment and let people be free within that environment and sort of direct them a bit, but I can’t say, “You go here and stay like that.” Everything has to be free…. I like to think of my photo shoots as happenings. I am really inspired by the ’60s and happenings and gatherings and Woodstock and stuff like that.

BLVR: Right, your photographs remind me of that era. Of course, your photographs have a lot less facial hair and more tattoos.

RM: I love streaking and I love nudism, the sort of everyday things that nudists do. All those things really inspire me. I take those as a starting point and then adapt them to the world that I want to create.

BLVR: It’s interesting, too, because when you look at the photographs you wonder what’s happened before and what’s happened after; you start to create a narrative by looking at the photograph. It looks like a lot of fun— not for me personally, I would hate to be naked in a tree—but for them it looks fun. It looks as if there’s a lot of interaction. Is that true?

RM: There is lot of interaction and it’s definitely fun. I mean—

BLVR: It’s work, but it’s fun.

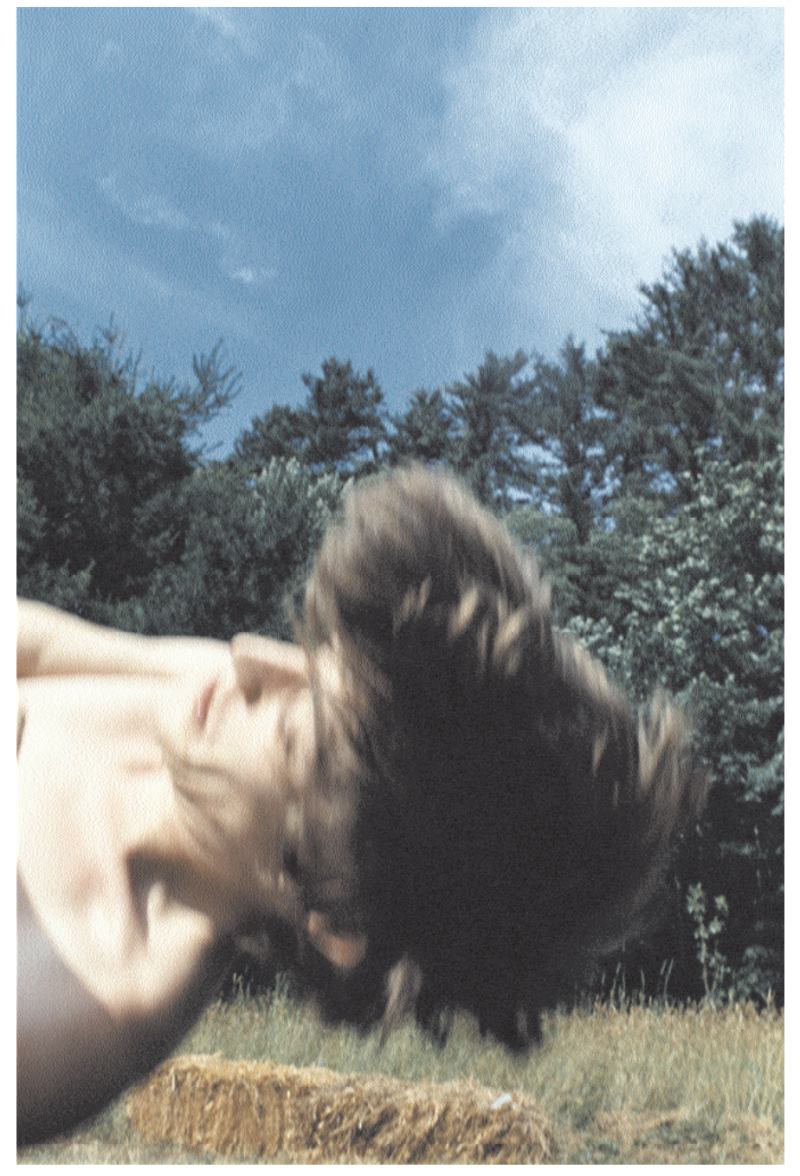

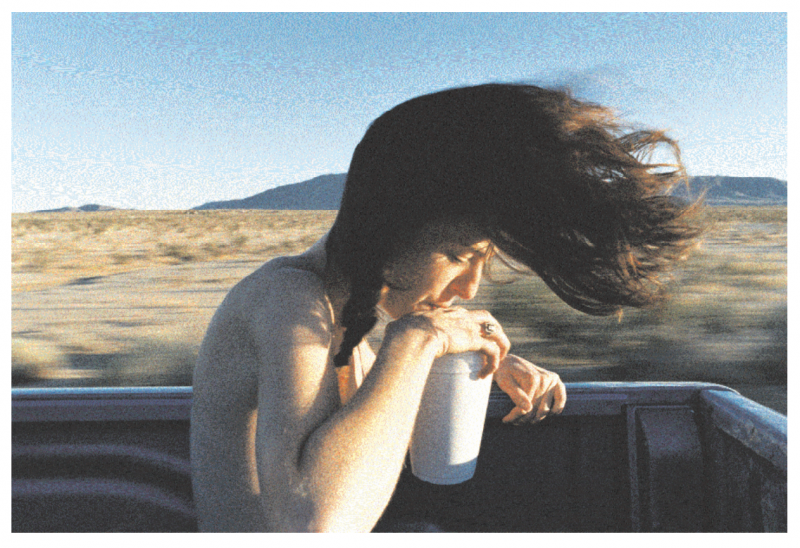

RM: It’s work, but it’s fun. I wouldn’t be doing it if it wasn’t fun. I want my work to be fun, because I work all the time. I never stop working. I mean rarely. I have never taken a vacation. But when I am actually shooting is when I am happiest. When you come up with an idea and then you get everything together and you get all the people and it’s actually happening in front of you—it is something. I think, Look at this crazy situation that I’ve set up and all these people are naked and doing these activities. When you look at the photographs they become something completely different. They become more romantic—the composition and the lighting—but if you are at one of my photo shoots, it’s completely ridiculous. I mean, like that photograph. [He points to the photo called Dakota (Hair).]

BLVR: I love that photograph.

RM: The girl is in the back of a truck drinking from this large foam cup, her hair is blowing in the wind, the sun is setting, she’s topless, and you know that photograph feels—it gives you this feeling of freedom, I can’t explain it. But actually seeing the process of how that photo was made is funny. There was a truck of marines behind us, and these guys were yelling at Dakota, “Show us your tits!” Or the photograph that’s called Tim Falling. That photo was made on a trampoline, and I had him falling until he couldn’t fall anymore, almost two hours. So it’s just him falling and falling and falling and a lot of my photo shoots are like that. There is serious repetition going on of those actions to make the perfect photograph where everything lines up, where the gestures are perfect, the lighting is perfect, the composition works, the mood is right, and it feels very real—there is a lot of work that goes into making it look very easy.

III. IRREGULAR REGULARS

BLVR: I read that you obsessively collect all kinds of imagery.

RM: I am a complete image hunter. Before I do my photo shoots I have a log of images that inspire me. I combine ideas from them to make my own images. I go to the New York Public Library’s picture file and I research words to find photographs. I have these lists of subjects that I’m interested in. I take all these images, scan them, and put them in these binders. We take these binders along with us on the road and use them as a starting point for a lot of shoots.

BLVR: You show them to the other people on the shoot?

RM: Yes. I’ll say, “This image is the inspiration. This is sort of what I am going for; this is going to be the starting point.” That’s where we start but then it never ends up like the image you started with. It’s always something completely different. But at least the people have that in their head—the feeling and the color and the mood and the spirit of the photograph.

BLVR: And you keep all those books?

RM: Oh yes, I keep everything. Actually, there’s one…. [Holds up a binder.] That’s a book of images that inspired me for last summer’s trip. [The binder is filled with pictures of naked people doing various nonerotic things: mowing the lawn, having a picnic.]

BLVR: You often use the same people as subjects. When you find someone who works well for you, do you want to photograph them over and over again?

RM: Absolutely.

BLVR: That’s interesting, because the Morrissey Irregular Regular pictures have to be so much more random in terms of the people you end up photographing. I mean, you’re not conjuring it at all. You have to find that person in the crowd who appeals to you or is interesting to you.

RM: And it is anonymous. It’s the time that you spend with that person during a concert so all their sensory levels are broken down because they’re watching Morrissey: the music is so loud, there is this environment of stage lighting that creates a mood, and then you’re surrounded by hundreds of people on every side of you, squished together. So finding people in the crowd, it’s really… I talked about being an image hunter before, but then you have to be sort of a people hunter. You have to navigate through the crowd and find the people who are entranced or hysterical. Then you also have to be confident to photograph somebody while the concert is happening and if this person kind of looks at you… If you were at a concert and I went up to photograph you in a crowd—even though you are watching the concert—you are still aware that I am doing something. You might be freaked out a little bit.

BLVR: Definitely.

RM: And then I have to sort of explain to somebody through body language that what I am doing is for the purpose of, like, a better good [laughing].

BLVR: How do you do that?

RM: I’ll motion to Morrissey with my hand and then the camera and then the person—then you sort of just have to continue shooting, you have to develop a sense of trust with them within seconds…. Then there is a motion of the finger like a wheel going, meaning I am going to continue doing this and then I point to them to say, “Pay attention to Morrissey, don’t look at me.” Because lots of people will think that you want them to look at you because you are taking their picture and you want them to continue doing what they are doing. Then they understand what’s going on; I mean, not fully understand, but there is this kind of understanding.

BLVR: Do most people like getting their pictures taken?

RM: Yes, I think lots of people like it. But there are some people who don’t like it, and it’s obvious to me right away if a person does not want to get their picture taken. But it’s nice because you could just move through the crowd and there are so many people who are available to photograph. I look for someone who is really getting off, who is really losing their mind or, if they are not losing their mind, then they are really in their own world and they have this gaze—they are hypnotized by Morrissey.

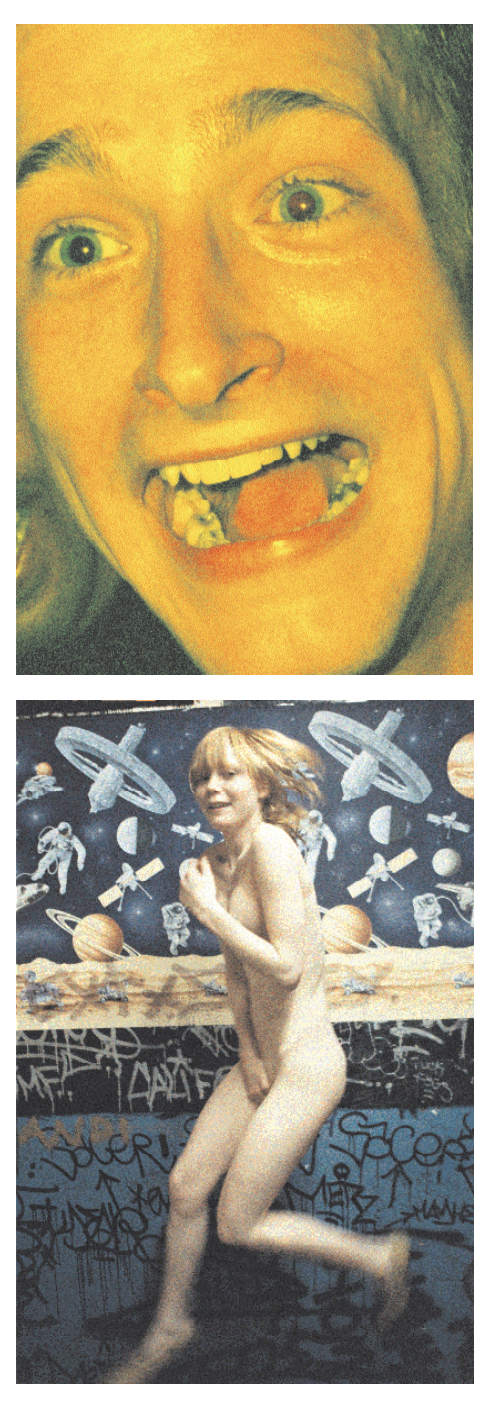

BLVR: How did you get the look of those photos? The colors?

RM: I sort of developed this process over time. I experimented with the film. I would run the film through the camera before I went to the shows, and I would expose it to all different kinds of light. I’d expose it to daylight; or I would expose it to sunsets; or I would expose it to TVs and to room lights. Then I would put it back in the camera and shoot it at the show and the colorful stage lighting would be mixed with the initial exposures. Then I would take it to the darkroom and even work on it more to achieve this unique color palette.

BLVR: Where did you get the idea for doing that?

RM: Sometimes when I would be shooting projects over the years, I would drop my camera and the camera back would pop open and the film would get exposed to light. When I would get the film back, it would have these yellow and red and sometimes green or blue bleeds across the image. And then I thought, How can I expose film to light and control it, so it’s not really gigantic bursts of yellow or something like that? How can I get that and control it? So I started experimenting with the film, and I figured out how to achieve different colors, how to get these really strange greens or really intense pinks or these blue-blues. And what light to expose it to and how much light to expose it to.

BLVR: What does the title Irregular Regulars mean?

RM: It’s something that Morrissey says to the audience. “Are all the Irregular Regulars here tonight?” There are so many fans who are dedicated and have been following him since the beginning of his career; there is something a little irregular about that. I consider myself and my friends and the people I have met along the way—we’re the Irregular Regulars. So that’s what the title refers to.

BLVR: I love the photographs. Everyone looks happy. Are there never pathetic or lonely people at Morrissey shows, or are you just not interested in that?

RM: No, no pathetic or lonely people in my world of photographs. It doesn’t exist.

BLVR: It’s just not interesting to you or you just don’t—

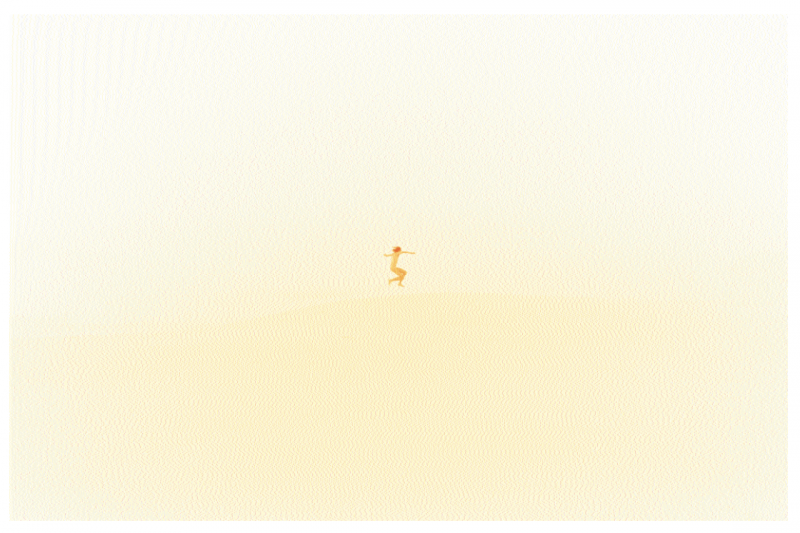

RM: The photographs I choose and group together aren’t really reality—it’s not real life. Someone once said to me that it’s always warm in Ryan McGinley photographs. You never feel cold. You always feel like you are in the sun. And I love that.

BLVR: And is that why you always use young, goodlooking people?

RM: I am interested in youth culture. That’s always been part of it. I mean, it’s me, it’s what I know. Over time I don’t know what’s going to happen. Will I continue to photograph young people as I get older? Maybe. Maybe I’ll make films. Maybe I’ll make a romantic comedy. Maybe I’ll photograph old people. I would just like to evolve as an artist and take risks. There is something about youth and that point in your life when you’re very free. I usually work with young artists. I like to photograph people who are in college or right out of college—there’s this sense you can do anything. That’s why a lot of these people come on my trips. They do have the time to go away for a few months.

BLVR: Your subjects are young and beautiful, but they aren’t these sculptural, perfect people.

RM: They aren’t models.

BLVR: Yeah, they’re not models, so there is a fragility and there is a sort of humanity in them. Some of the kids in your pictures have, say, chipped blue nail polish or a black eye. They still look beautiful, but it’s an earthy kind of beautiful.

RM: I don’t like it when people are too pretty. They have to have character. Something a bit fucked up about them.

BLVR: Do you have any friends who aren’t young and beautiful?

RM: I have lots of older friends. But they’re just not part of that world I want to create. It’s really a world—you have to remember that. People look at photographs and believe them as truth and they always will. People look at my photographs and think this is real—this life exists. Even if they know that it doesn’t, they want to believe a life like these photographs exists.