At first, the cab driver couldn’t find it; the empty fields to the left and the low trees to the right were covered in snow, and there was no looming Hamptons mansion at the end of the road. “I don’t think there’s anywhere else here,” he said. But then it appeared: a modest, low-slung house glimpsed through a tunnel in the trees. As we pulled into the drive, it was clear that Peter Matthiessen’s home for the last six decades wouldn’t be considered a normal home anywhere. An enormous skull—the cranium of a fin whale—was braced against a wall of the house, and clusters of other artifacts rested half-buried in the snow: driftwood, stumps, shells, small boulders, sculptures. I rang the doorbell and no one answered, and for a moment it was completely quiet: rain dripped off a row of icicles hanging from the roof. And then a kindly, deeply lined face peered through the glare in a pane of the front door.

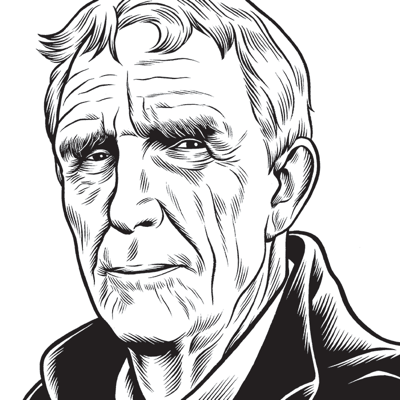

What to say about Peter Matthiessen? There was no one quite like him: a writer and thinker, a naturalist and activist, and a fifty-year student of Zen Buddhism who, as his publicist put it, “lived so large, and so wild, for so long.” He was the only person ever to win the National Book Award for both fiction (Shadow Country, 2008) and nonfiction (The Snow Leopard, 1979), along with a bushel of medals and prizes for his elegant but unsentimental books (of which there are at least thirty), most of which concern the wild places, animals, and people “on the edge,” as he said, of the farthest parts of the globe, where pre-human landscapes and premodern pasts are (or were) still visible.

These edges are, more or less, where he spent his adult life. A précis of his travels is a bewildering list, and includes the Himalayas, the islands of the South Pacific and the Caribbean, the Mongolian steppe, Africa from the Serengeti to the Congo basin, South America from the Andes to the Amazon, the boreal forests of North America and Siberia, and a “musk ox island in the Bering Sea”—and that’s far from exhaustive. These travels would be remarkable enough, but he also cofounded the Paris Review, in 1953 (while working undercover for the nascent CIA); a few years later he was a struggling novelist and commercial fisherman using nets and dories off Long Island’s South Shore. Sixteen years after that, he was working as a labor activist with Cesar Chavez, and thirty years on, his book In the Spirit of Crazy Horse: The Story of Leonard Peltier and the FBI’s War on the American Indian Movement...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in