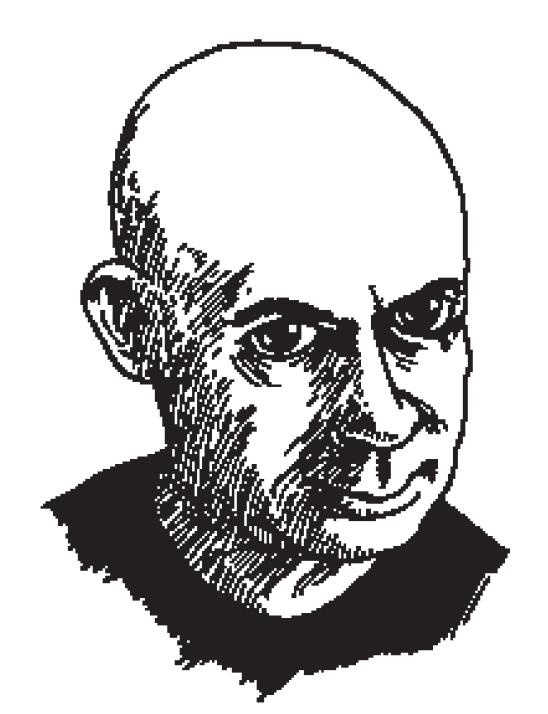

Mick Napier can be an asshole. At a party a few years ago, I asked him for a cigarette and he handed me a card that read: “You have just asked me for a cigarette. You should know that they are widely available at many stores. Perhaps you could buy some for yourself.” It was funny, slightly mean, and honest. Just like Napier.

But that’s just Napier on the surface. Underneath, he’s a fairly mellow guy, not the type to be the center of attention or anywhere near it. If you’re a friend or have gained his trust and respect, he’s as warm as anyone you’ll ever meet. But when you’re the founder of the Annoyance Theatre, an award-winning director at the Second City, and generally the pre-eminent teacher and director of improv and sketch comedy in Chicago, you become the center of attention whether you like it or not. His directing expertise has been sought out by everyone from Steven Colbert, Tina Fey, Rachel Dratch, Horatio Sanz, Nia Vardolos, Andy Richter, Jeff Garlin, and David Sedaris. A student borrowing a cigarette from Mick Napier is probably just looking for a conversation about improv, or perhaps hoping that a little of his magic will rub off. Napier knew it. If you want some of his time, you have to sign up for his class like everybody else.

Or you can do what I did and convince a magazine to let you interview him. I sat down with Napier at Square Kitchen, one of his favorite hangouts in Chicago’s Lincoln Square neighborhood. It’s the kind of setting he likes: quiet, unassuming, and with a well-stocked bar. It’s an odd fit for a man who has become a larger-than-life guru of improvisation. But according to Napier, being out of the spotlight feels pretty good sometimes. Just give him a pool table and the Lifetime Network and he’ll be just fine.

—Peter Grosz

I.“IF WE HAD A HUNDRED PEOPLE IN THE AUDIENCE, MAYBE FIVE WOULD BE LAUGHING AND THE OTHER NINETY-FIVE WOULD JUST SIT AND STARE.”

THE BELIEVER: The Annoyance grew out of Metraform, a company you started in 1987. The company’s first play, if I remember correctly, was called Splatter Theater.

MICK NAPIER: That’s right. We painted the walls of the theater white during the day, and by the end of the night the walls were splattered with blood. We killed off thirteen to nineteen people during every show. It was a parody of Friday the 13th–type slasher films. Not long after that, we did Co-ed Prison Sluts, which ran for eleven years.

BLVR: Was there anything else going on in Chicago at the time that was similar to what you were doing at the Annoyance?

MN: There wasn’t anything. There was a splattering of…

BLVR: Splattering?

MN: A smattering of shows here and there, but there wasn’t a theater devoted to this kind of content that was based in improvisation.

BLVR: Second City was based in improvisation, but I don’t think they were doing shows that involved throwing blood on the walls.

MN:The Annoyance is mostly remembered for its subversive content, but that’s not necessarily why I was proud of it. We were the first in Chicago to dedicate a theater to full-length plays and musicals that were developed through improvisation and written through improvisation, as opposed to improv as an end to itself or sketch comedy.

BLVR: A few of the shows you did at the Annoyance ended up getting some national attention. Probably the most famous one was The Real Live Brady Bunch.

MN:Yeah. When Jill Soloway and Faith Soloway came to me with the idea…

BLVR: Jill Soloway, who now writes and produces for Six Feet Under?

MN: That’s right. They told me that they wanted to do a stage version of The Brady Bunch, and I thought it was insane. I still think it’s insane to merely reproduce a television show onstage.

BLVR: The premise was basically performing old scripts from the TV show. Was it word for word?

MN: Word for word and action for action. It was a trip. And then it got so successful. It got national press, and we took the show to New York and Los Angeles. It was a great experience for everyone, but something that… I guess I’d say it was divisive. I had a lot of mixed feelings about Real Live Brady Bunch at the time.

BLVR: Was it because the show got so much bigger than you expected? It kinda took on a life of its own.

MN: I think I had more of a philosophical bent about what the Annoyance was supposed to represent. You know, the integrity of pure creation, blah, blah, blah. But in retrospect, I’m glad it happened because it created a great deal of opportunity not only for the Annoyance but also for many individuals.

BLVR: It launched a lot of careers. Andy Richter was a part of that cast, wasn’t he?

MN:Yeah, Andy came from that move.

BLVR: And some of the actors went on to Saturday Night Live.

MN: It was a really wild period. There was an article about the show in GQ magazine, if I’m getting all this right. I can’t fucking quite remember. And then [Saturday Night Live producer] Lorne Michaels, who had come to the Annoyance a few times before, became more excited about us. He came to see a show called The Miss Vagina Pageant, or was going to, because it featured a lot of women and he was looking for women.

BLVR: I’m sure he was happier to see The Real Live Brady Bunch than The Miss Vagina Pageant.

MN: I don’t know. At one point, Lorne saw a show at the Annoyance called Poo Poo Le Arse. It was something I put together that had a Dada sensibility. It didn’t make a lick of sense. If we had a hundred people in the audience, maybe five would be laughing and the other ninety-five would just kind of sit there and stare. I was usually the sixth person laughing during every show.

BLVR: Did you enjoy that people weren’t laughing, or is your sense of humor just out of synch with most audiences?

MN: It’s probably the latter. I felt bad that more audience members didn’t laugh, but I loved how purely absurd it was. If it made sense, then it wasn’t doing its job.

BLVR: And what did Lorne think of it?

MN: He liked it because he appreciated the Dadaism. I was very surprised. He said he liked avant-garde and absurdist theater. He really enjoyed it.

BLVR:The Annoyance was sometimes perceived as just crazy or just shocking…

MN: Or dirty.

BLVR: Or just dirty. But it never seemed like your goal was to be dirty for dirty’s sake.

MN: Not at all. My sense of humor is pretty dark, but I didn’t fancy the Annoyance as a sophomoric or dirty theater. We did a lot of subversive stuff, but I always felt like it was done with sophistication and intelligence. It was horrible when directors would come in and not understand that sensibility and go blue. If something is just blue, that makes me sick. I hate that. I like to think that even Co-ed Prison Sluts, which had a song that glorified child molestation, was protected by innocence and had its own intelligence about it.

II. “IF THERE’S A GUY ONSTAGE OR ON-SCREEN REPEATEDLY DROPPING A PEANUT AND SAYING THE WORD ‘POODLE,’ I THINK THAT’S FUNNY.”

BLVR: What do you personally consider to be funny?

MN: That’s a great question, because I don’t think that a lot of the stuff I direct is funny. The things I like are a little off, like Poo Poo Le Arse. If there’s a guy onstage or on-screen repeatedly dropping a peanut and saying the word “poodle,” I think that’s funny. I love repetition; I love the same thing over and over. I like very, very obscure things.

BLVR: Is it that Dadaist sense that it’s about nothing? It’s not a typical sketch comedy cliché, like a couple discussing why they don’t have sex anymore, or President Bush’s Iraq policy, or something like that.

MN: Yeah, I don’t think those things are as funny. There’s a play I’ve always liked called Jet of Blood. It’s by Antonin Artaud, who wrote books on theater and criticism. He’s the father of Theatre of Cruelty, but he didn’t do much with it except Jet of Blood, which is only two pages long. One of the stage directions is: “When the lights come up, all of the actors are dead. Only the nun and the whore are left. They are eating each other’s eyes.” That I find funny.

BLVR: How do you translate that to people who wouldn’t normally be drawn to those ideas? Was it a challenge to make Poo Poo Le Arse entertaining to someone who just walks in off the street?

MN: It was. We had an introduction before the show that described a little about what Dada was. We warned the audience that what they were going to see would make no sense. We tried to do it in an unapologetic way, but we also created a context for it.

BLVR: Context and Dada? That kind of dilutes it.

MN: That’s true. Because it’s about not having context.

BLVR: Is it a lost cause then to try to explain Dada to somebody who is just never going to get it?

MN: Maybe, but I’d do Poo Poo Le Arse again, or something just like it. ’Cause it really makes me laugh.

BLVR: What about things that you don’t find as funny? Do you get irritated by the safe, predictable comedy that most audiences and actors gravitate towards?

MN: There are certain kinds of material I won’t allow in a show that I direct. Like parodies. I hate parodies of game shows, parodies of songs, parodies of damn near anything. Impersonations don’t turn me on. I don’t ever find them funny. I think the last impersonation that I actually laughed at was Chevy Chase doing Gerald Ford on Saturday Night Live.

BLVR: The non-impersonation of all non-impersonations.

MN: Exactly. I also have a hard time with scenes that are, in my opinion, kind of “done.” Like a group therapy scene, an Alcoholics Anonymous scene, a confessional scene, bringing home a date for any reason at all….

BLVR: To kill them, maybe?

MN: Bringing home a date to perform Dada for the parents.

BLVR: Bringing home a date over and over again, dropping a peanut.

MN:That would make me laugh.

BLVR: So as a director, you just want to be surprised?

MN: Yeah, I guess. I just saw the movie Sideways and I really liked it. The comedy comes from a very organic place. With the often goofy spectrum of improvisation—character-wise and premise-wise—it’s refreshing to have a scene find its comedy from something real.

BLVR: It seems like there are two things that can trigger a reaction in you: Something that’s so real that you have to laugh or something that’s so ridiculous that you have to laugh.

MN: I’ve never thought of it that way, but you might be right. Everything in between, I feel like I’ve seen and seen and seen again. My motto is, “Improvisation is always different but it’s always the same.” Technically, it’s always different, but there is this spectrum of the same moves that happen all the time.

BLVR: When was the last time you directed something that truly surprised you?

MN: Well, I just finished a new mainstage show for the Second City, and it had some nice moments. Brian Gallivan and Jean Villepique do a scene about her having cancer, and he tries to deal with it from a football coach’s point of view. And in the same show, Brian Boland does a racist monologue, which was a huge challenge to protect, to have the audience be okay with it. He’s such a good writer that he pulls it off. I’m also pretty happy that this was the first mainstage Second City show to have the word “cunt” in it.

III. “I COULD NEVER UNDERSTAND WHY THE WALLS WERE ACTUALLY TALKING.”

BLVR: You have a reputation as a bit of a pool enthusiast.

MN: I love playing pool. I always have. I’ve often said if I could be a professional pool player, I would give everything else up.

BLVR:When did you first start playing?

MN: Twenty years ago, back in college. I played a little when I was younger, but I got serious about it in college and then in Chicago. I used to play every single night without exception. If I was going out of town, I would check the area to make sure there was a pool hall nearby or a pool table in the hotel. And if there wasn’t, I would book a different hotel. I was crazy obsessive. I’ve been in some weird pool halls in my life and been in many, many fights.

BLVR: Because of a drunken pool game?

MN: All the time. I’d get into an argument with someone before a game. I’d pull the 8-ball out of the rack and hold it above the corner pocket and tell them, “If you say another word, I’ll drop it.” I’d do it, and because they’d always be bigger than me, they’d body-slam me on the pool table. They’d draw back to hit me, and the bartender would have to catch their arm before they beat the fuck out of me.

BLVR: Would you ever play for money? Or try to hustle somebody?

MN: I did it a couple of times, but I’m not good enough to pull it off. Not the pool part but the acting part, oddly enough.

BLVR: That’s a line that you aren’t able to cross?

MN: Yeah. Seeing that happen and having been hustled and having a lot more people try to hustle me, I just couldn’t do it.

BLVR: Did you play at the old Lakeview Lounge on Broadway?

MN: Oh, yeah. Usually until four in the morning. They play Last Pocket there.

BLVR: What’s that?

MN: Usually in 8-ball, you hit your last object ball on the table (before the 8) in a pocket. Then you hit the 8 ball in any pocket you call. In Last Pocket, you have to hit the 8 ball into the same pocket that your last object ball went into. So there’s a lot of banking in that.

BLVR: Did you get good enough to bank using the dots on the table?

MN: I never used the dots, but I got pretty decent at banking playing Last Pocket. I don’t think anyone uses the fucking dots.

BLVR: That’s what they’re there for, right?

MN: Yeah, but the weird thing about pool is that the speed and the humidity in the room and the cushion wear and all of that effects the angles. It’s not like you can hit a pool ball at that dot and have the angle of reflection be exactly equal every time. If you have high humidity, the felt is going to be a little more saturated with water, which means there is going to be a little more pull on it. And if you hit a ball slow against the cushion, there’s more friction. The ball comes off at a wider angle than if you hit it fast.

BLVR: If you hit it harder, would it bank off more sharply?

MN: It kind of pushes into the cushion, which is vulcanized rubber, so it actually reflects wider. If you hit a ball faster into the cushion, the angle is sharper.

BLVR: Other than pool, do you have any recreational interests that don’t involve comedy or improv? Anything that might surprise us?

MN: I’m a huge Lifetime Network movie fan.

BLVR: Really?

MN: Oh my god, I watch so many Lifetime movies. I love Lifetime movies.

BLVR: What was the last one you saw?

MN: Oh shit, it was probably yesterday. I feel like it was called Secret at my Door, but I’m not sure.

BLVR: That’s a pretty good guess, anyway.

MN: No, it was The Secret Walls.

BLVR: And what was it about?

MN: A woman moves into a new apartment in New York—no, Chicago—a big loft apartment with her husband, and she hears talking in the walls. They come to find out there’s a conspiracy involving the FBI, which is trying to bust her husband. They’ve wiretapped the whole apartment.

BLVR: They wiretap the apartment with speakers of the FBI talking?

MN: I could never understand why the walls were actually talking. Yeah, I love Lifetime movies.

BLVR: Is there that escapist element of “this is so silly”?

MN: Yeah, completely. But I also just sit there and cry. Yesterday was all about screwdrivers, a blanket, and Lifetime movies. That’s a good day.

IV. COAL MINERS, CHICAGO & SATAN’S TOUR BUS

BLVR: Chicago has never had much luck establishing itself as a hotbed for TV and film, which tend to thrive in places like L.A. or New York. Why do you think that is?

MN: Chicago draws a lot of talent, and because of all the checks and balances and constant challenges, the theater work is really, really good and consistently funny. But sometimes it’s difficult to translate that into a different medium like film and television. It’s hard to capture its original quality. Industry-wise, Chicago is still learning about film, but it needs to grow up in regard to production value. There’s a mentality that in Chicago we’re “just trying.” That you’re not really doing something if you’re doing it in Chicago. When I directed my film, Fatty Drives a Bus, I kept thinking,“This isn’t real. It’s not a real movie. It’s kind of a play movie, because I’m doing it in Chicago.” I had to fight that constantly.

BLVR: It’s like the creative community here needs an ego boost.

MN: It’s true. I sometimes joked that Fatty Drives a Bus should have been called Film School, because it was the first time I even thought about doing a movie. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. But it worked out fine. Troma bought it and that means they distribute it on video and it’s in that class of Troma films, which it should be. I’ve learned that there are little cults of people in the United States and Canada that get together and see Fatty Drives a Bus.

BLVR: Give us a quick plot summary so that people are enticed to go see it.

MN: [Laughs] It’s basically about Satan, who comes from Hell to drive a tour bus and attract souls onto the tour. That’s it. And he’s being pursued by Jesus Christ.

BLVR: Of course. Good for Jesus.

MN: It was all improvised.There was never a script for it, and I like about a third of it.

BLVR: Is there a viable way to create films through improvisation? Obviously a TV show like Curb Your Enthusiasm proves that you can be incredibly successful without needing a script at all. Can that work on a feature film scale?

MN: I think so, if you have talented people and a great structure for beats. And then even with all that, you’re in for a lot of editing hell. I’d spend hours in the editing room yelling at the video monitor, “Please, Beth, turn your head to the left so I can cut this!”

BLVR: The Second City is trying to sell TV ideas to L.A. Are you involved in that?

MN: I am. I pitched for Second City at Fox.

BLVR: What is that experience like?

MN: Terrifying and nightmarish and I hate it. I hate pitching. I have mixed feelings about Los Angeles. I love the weather. God, I’m so jealous of their weather. The weather, the weather.

BLVR: Well, it’s hot in hell, too.

MN: Yes, indeed. I can’t wait. It’s really a quality of life issue that has kept me from going to Los Angeles. I can’t spend my life having those kinds of conversations and devoting myself completely to that industry. Because, ironically, I fucking hate talking about what I do and I hate talking about comedy.

BLVR: This interview must be hell.

MN: It’s the worst fucking experience of my life.

BLVR: Does that modesty about your career have something to do with your upbringing? Most people aren’t aware that you were raised in a small, rural town.

MN: I was born in Hazard, Kentucky. It’s little town about two and a half hours southeast of Lexington. It’s coal-mining country. My dad was a coal miner and he moved our family to Ohio when I was young to get out of the coal mines.

BLVR: How old were you?

MN: I think I was one or two. We went back there a lot. I enjoy my Southern roots. It’s nearly Appalachian just on the other side of Hazard and it’s really trippy, but it’s been a core of everything I do. I identify with it and feel a part of that. My dad owned a construction company so I did construction while I grew up. It taught me a work ethic and made me less tolerant of whiney actors. I’ve laid sewer pipe for ten hours. I’m not afraid of work and I get a little pissy when people get pretentious about acting.

BLVR: Having achieved success on a citywide scale with the Annoyance and the Second City, do you ever feel like,“I need to break into the next level?” Or would you be perfectly happy doing theater in relative obscurity for the next forty or fifty years?

MN: I’d like to move to New York eventually, and maybe start directing and teaching there. And I would love to get the Annoyance re-established here in Chicago. We’re in the process right now of renovating a space, which is taking forever, and as soon as I feel that’s stable as a business, I’ll go to New York.

BLVR: Would you want to start some sort of Annoyance-like theater in New York, or would you rather just be a teacher and director?

MN: My big goal would be to have an Annoyance Theatre in Chicago and an Annoyance Theatre in New York, and by the time I’m fifty-five, open an Annoyance Theatre in Key West, Florida, where I’d spend a lot of time developing plays and musicals.

BLVR: Bottle of scotch in one hand…

MN: And a margarita in the other.