Michael Bell has spent the past twenty years tracking down vampires in the cemeteries of southern Rhode Island, northern Connecticut, and Vermont. His book, Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires (2001) documents his journey into the dimly lit world of nineteenth-century vampire practice, where, when one’s children began to die from a mysterious, crippling disease, it sometimes became necessary to exhume the bodies of the dead, find out which one was possessed, cut out the heart of the corpse, burn it to ashes, and feed it to the living in order to put an end to the vampire’s reign. Although Bell’s vampires never wore capes, hissed, or even bothered to leave the grave, he maintains that they were much more terrifying than the monster we’ve become familiar with through movies and television. “They killed their kin while still lying, apparently dead, inside their coffins,” he says. “How can you escape from something like that?”

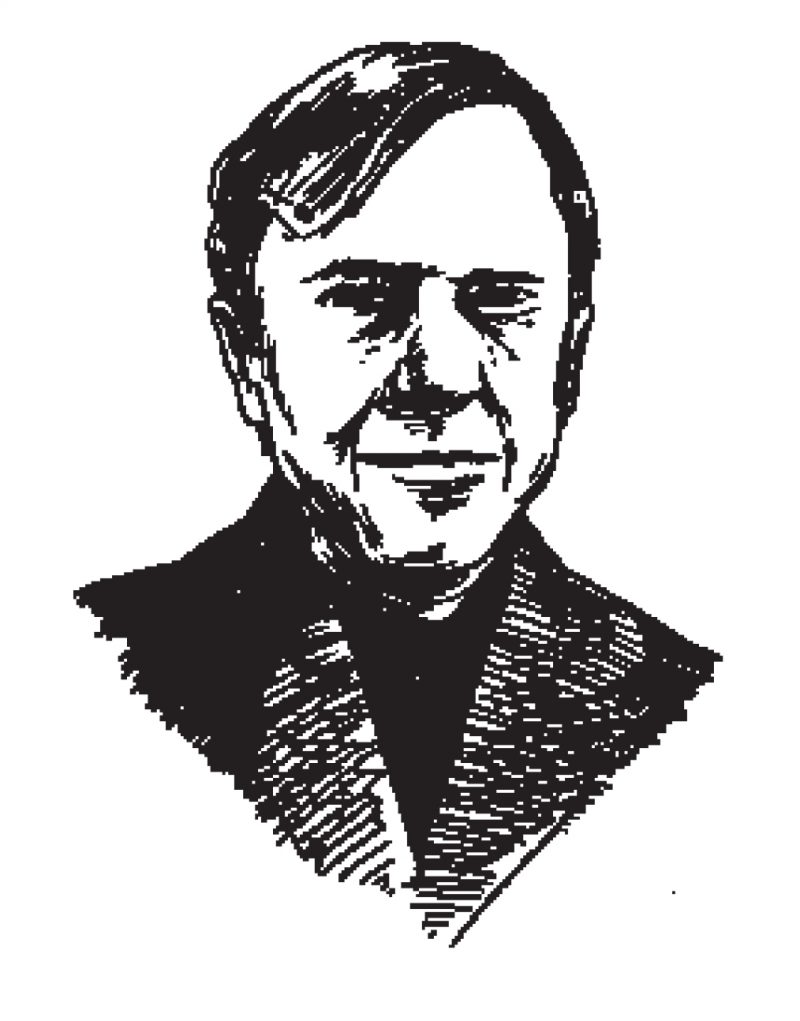

More terrifying, perhaps, is that when I met Bell at a small restaurant around the corner from my house, he looked so much like a vampire hunter—at least, the way a proper vampire hunter should look—that I hesitated to call him over to my table. He is a narrow, handsome man who radiates a vehemence not unlike Christopher Plummer in his turn as Dr. Van Helsing in Wes Craven’s Dracula 2000. It is so easy to picture him, wooden stake in hand, struggling atop a mound of freshly dug soil with a shrieking, reanimated corpse, that I found it difficult to focus on the interview at all. But some two hours later, I know a few things I did not know before. The good news: The golden age of the vampire seems to be over. The bad news: You may be alive today only because a distant relative ate the charred remains of a possessed family member.

—Matthew Derby

I. “DRIVING THE STAKE IS

CERTAINLY ONE WAY TO DO IT.”

THE BELIEVER: How do you know when you’ve found a real vampire?

MICHAEL BELL: Well, when you get familiar enough with the vampire tradition, there are certain cues and motifs—little narrative elements that stand out—and make you realize “OK, this is probably something I’m interested in because it’s similar to the vampire tradition,” and then there are other elements that seem to be directly from popular culture that don’t fit, and you can tell pretty quickly one from the other. Basically I look for cases where the people involved were dying from a specific condition—where they exhumed the bodies, what they did to the bodies—cutting out the heart, et cetera. Those are the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in