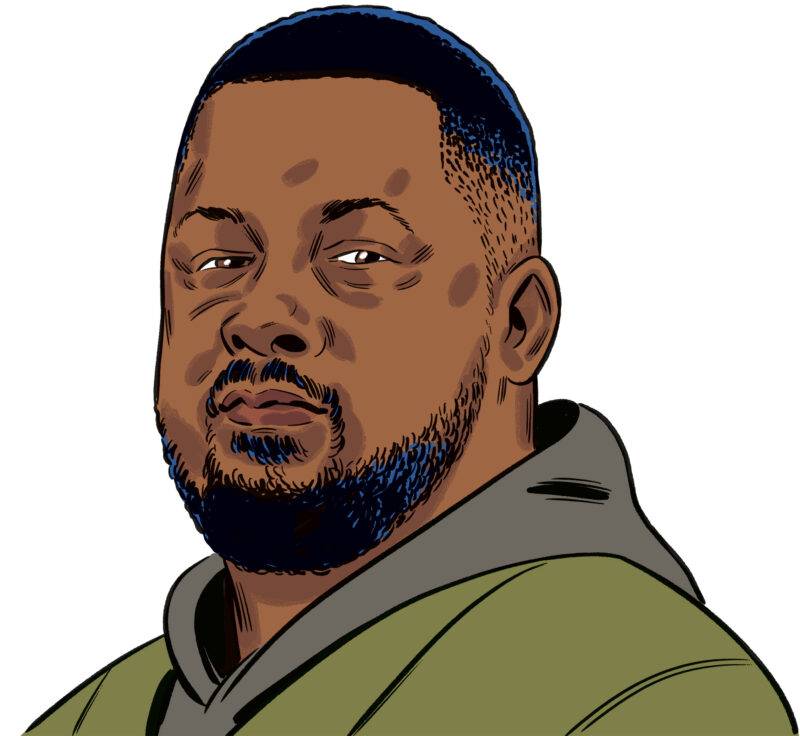

Sportswriters are rarely heralded as cultural pillars. But Marcus Thompson II is—to use a sports term—a GOAT. A former beat writer for the Golden State Warriors and a current columnist for The Athletic, Thompson does what any memorable voice of their time does, regardless of genre: he observes deeply and speaks with a catharsis-inducing realness.

With a golden hand that produces as many as four stories a week, Thompson offers nuanced commentary and provides a rare human window into the fast-paced world of the NBA. One day he’ll break the news of Steph Curry’s players-only speech inside a locker room of defeated Warriors, and the next he’ll explain how a single dunk may cause a tectonic shift in a franchise’s roster management.

Even though Thompson has built a remarkable decades-long career, he wasn’t born into the winners’ circle. He grew up in deep East Oakland in the ’80s and ’90s and attended Oakland Tech. Early on, he memorized the East Bay’s haphazard bus system, riding three AC Transit lines across the city by swapping out bus passes with his friends—the same buses that locals like Too $hort began their careers rapping about.

As a teenager, he relocated to Georgia to attend the HBCU Clark Atlanta University. After writing for Atlanta Daily World and graduating with a degree in mass communications, he returned to the Bay and landed his first journalism gig in 1999, covering high school sports at the Contra Costa Times (now the East Bay Times). In 2001, he began cranking out stories about the basketball squad at Saint Mary’s College of California, in Moraga, before eventually circling back to Oakland in 2004 to report on the struggling Warriors.

Today, the Warriors are seven-time NBA champions—and Thompson is one of the definitive sportswriters of his generation, having authored biographies of superstars like Steph Curry and Kevin Durant during Golden State’s dynastic run. In the span of a fog-burned week, I chopped it up with Thompson on multiple phone calls while he was on the verge of finishing a big project about LeBron James during the NBA’s free-agency period. I later ran into him at Chase Center before a Steph Curry buzzer-beating three-pointer sent us home in euphoria.

—Alan Chazaro

I. THE SECOND LAYER

THE BELIEVER: As a fellow Bay Area writer, you’re someone I’ve wanted to connect with for a minute. We’re both in the middle of reporting stories right now, so thanks for taking the time.

MARCUS THOMPSON II: I appreciate that. We gotta represent one time for the Bay. You know Pendarvis Harshaw, right? That’s my guy. I read everything he does.

BLVR: Yup. He’s one of the ones. His writing, honestly, inspired me to leave my career as a high school teacher and pursue journalism. I saw what he was doing and was like, Damn. I want to do that, but with my Mexican American perspective.

MT: That’s what’s up. Being Mexican is one of the more undertold stories, especially in Oakland. I actually remember researching the Harlem of the West on Seventh Street. It used to be a Black neighborhood, but it was also a profound Mexican neighborhood for a while. That was why there was Mexicali Rose and spots like that. It used to be mostly Mexican-owned spots, and people would just set up their shops all around there. Then they put the jail there, and you got the post office now, and the BART—that kind of changed things. But it used to be a thriving Mexican neighborhood at one point.

BLVR: That’s wild. I had no idea and never knew about that history.

MT: Yes. When the railroads came west, the Bay Bridge was created to essentially hate on Oakland. It changed things. The ports were huge in San Francisco. But the [Central Pacific] railroad made the Port of Oakland even bigger and more important. The last stop on the railroad was West Oakland. So there was a whole new economy growing there. The ship conductors, workers, longshoremen—that was Black, Latino, working-class. They all had jobs. Then San Francisco built the bridge [in 1933] because they wanted that commerce.

BLVR: My parents immigrated to Scrillacon Valley in the late ’80s, so I missed out on tons of local context like this.

MT: What did you say? Scrillacon Valley?

BLVR: Yeah. Most people call it Silicon Valley, but when I was growing up, the norteño rappers around there used to call it Scrillacon Valley. I say it jokingly. Kind of.

MT: That’s what I thought you said. I remember the Luniz album Operation Stackola. The one where they’re robbing a bank [on the cover]. At the top center it says “Scrilla National Bank.” Great album.

BLVR: Definitely a classic. That gave us “I Got 5 on It.” So what are you working on these days? I know it’s the NBA offseason, but you always seem to be putting in work. I just heard you on an episode of Hoops Adjacent this week.

MT: The Athletic is actually doing a podcast on LeBron; it’s this big series about his twenty years in this league. I got the Steph and LeBron episode. I had to write that today. I’m also writing about [Mike] Dunleavy becoming the GM [of the Golden State Warriors] and how gangsta his first move was. Trading [Jordan] Poole? That was savage. I’m also trying to find out more about Draymond Green’s situation. I don’t think he’s going anywhere. It’s free agency, what we call silly season. You never know what to believe, and everyone has an agenda. I have a few more weeks before I take some time off, but I’m grinding till then.

BLVR: How did your career as a beat reporter start?

MT: I was covering Saint Mary’s basketball in 2004 and Matt Steinmetz was the [Warriors] beat writer for the Contra Costa Times back then. I don’t know what happened, but they asked me to write about Erick Dampier leaving the team. Steinmetz was off. I had pitched to write about the Warriors here and there, but it wasn’t my job. Then they asked me again to write about Gilbert Arenas when he signed in Washington [DC]. I was like, Hold up. This isn’t my job. I didn’t know anything. I’m trying to call agents. The first piece was really hard. For the second piece they told me that if I wrote it, I’d become the beat writer. I wrote it, and a few weeks later, Steinmetz quit and I was the Warriors beat writer.

At the time, the Warriors weren’t a big deal. There was a writer from The Mercury [News] and The [San Francisco] Chronicle, and me. I had no connections. I had nothing. I started from scratch. I didn’t even know how to book road trips. I couldn’t just ask my bosses, because it felt like proof that I didn’t know what I was doing. Marc Spears was the one who helped me. I have to mention him. He was huge for me early in my career. He gave me phone numbers. Taught me how to book my trips. He had a map of where to stay in every city, how to rent cars, hotels near the arena that you could walk from, all of that. He was covering the Denver Nuggets at the time, and now he’s at ESPN. Back then, salaries were hard to get information on, and you needed an agent to give you a salary sheet. The agents had it, but it wasn’t common knowledge. I didn’t know any agents. So Marc gave me a copy of that. Spreadsheets printed on paper about how much money players were making. I didn’t know if I could do it. When I didn’t have much help, Marc just came through. He’s still that way. I would’ve failed, probably, if it wasn’t for Marc.

BLVR: I can’t imagine covering the NBA as a beat writer. It seems so competitive and hyper-paced.

MT: I’ve been doing it for so long, fortunately, so I can kind of survive without getting into all the other stuff. My contribution is my voice, more than anything else. Other writers can get the news. Woj [Adrian Wojnarowski] from ESPN, Shams [Charania], who’s with us at The Athletic. They cover it all, regardless. They’re gonna get it first. There was a point in my career when that’s how we lived as reporters. That was the value of a reporter—just to break the news. But now, in today’s landscape, I kind of live in the second layer. Someone will tell you what is happening. I’ll tell you what it means and why it matters. I’d rather serve the people who read me in that way. It’s healthier for my life. I did all that other stuff coming up in my career, so I get it.

BLVR: How was being a sports journalist different in the past compared with now? Pre-internet.

MT: When I started out, everything was in the newspaper. When you broke a scoop, you were king for a day. The competition couldn’t do anything about it. That was your day. I’d walk into practice all swagged out. Nowadays, you got two minutes. You bust your butt and make all the calls and in many ways neglect things that matter to you, like family. You burn time and get information and maybe you’re first and you got it and you’re out there with it, and for a lot of us, that’s worth about three minutes of pleasure. But the next person is right behind you. There’s a lot of scorekeeping internally on who reported it first. I don’t know how much readers care about that. In the end, you read who you read and follow who you follow. That’s what it is. That game to me, playing that, is like eating crawfish. Lot of work for a little meat.

BLVR: I honestly can’t stand crawfish.

MT: You need that special fork. All that for what? Give me some jumbo shrimp. You know how back in the day when you bought chips, and the bag was full with chips? Now it’s like half-filled with air, less chips. That’s like scoops today. Some are good at it, some aren’t. For me, it feels like not enough chips are in the bag no more. I don’t want to participate in that. I have a family. I don’t want that anymore. It’s like you skip dinner and then have to fix things with your wife later. I’ll do the work, but my goal is to be more of a voice and provide fuller context rather than being the first person to tell you.

II. A CRAB IN A BUCKET

BLVR: How did your time at Clark Atlanta University prepare you to become the kind of writer you are? When you left Oakland at a young age and slid over to the South, what did you gain from that pilgrimage?

MT: “I went from Oakland to Atlanta with my top down / $hort Dog, my shit is nationwide now.” I was so eager to get up out of here when I left. All it did was make me appreciate where I’m from even more. It made me appreciate Oakland, the Bay, our culture, our lifestyle. Atlanta was great, but when I graduated, I only wanted to get up out of there. But still, when I left the Bay, I couldn’t leave fast enough or get farther away than I did. Atlanta was way away. I told myself, I don’t want to be able to walk back home to Oakland.

BLVR: Oakland was such a different place back then.

MT: Coming up, we didn’t even have the outlets available like we do now. It was just rap, sell drugs, or if you’re good enough to make it in sports, do that. Or, for some, go to college. That was a clear route for me. I wasn’t a good athlete and I wasn’t gonna sell drugs; that just wasn’t me. College was my way. That’s what I was taught and what I believe. Finish school, all that stuff. I knew that wherever I went, I just wanted to accomplish that and not be sucked back into the clutches of poverty and trauma. I understood back then what it was to be a crab in a bucket. If something happens, it pulls you back. I wanted to be far enough that it couldn’t pull me back in.

BLVR: So why Atlanta?

MT: There was a girl in my neighborhood who went to Clark, who was a year ahead of me, and she told me to come. I remember being on the plane, flying to Atlanta, first time on a plane. You know how on the planes back then, they had basic screens that folded down for everyone to see? They would show a movie that everyone had to watch, and at the end they would show the map and you could see how far you’d traveled, the trajectory, flight path, all that. That’s the first time I realized where Atlanta was on the map of America. The plane was approaching Georgia and it hit me. And I straight started crying, like, Yo, what have you done? I’m by myself. I’m going to college. I don’t know nothing. I’ve never been out of Oakland. I couldn’t tell you how far three thousand miles was. Boy, I was straight crying.

But being in Atlanta and learning a different way of life, I just remember missing the Bay. Especially the diversity. At the time, Georgia wasn’t particularly advanced. It wasn’t even a sidewalk on every street, know what I’m saying? The stoplights were hanging from, like, a wire. It felt like the country with a k. Now it feels like a major metropolis, but in ’95 it felt like the country. Even in the hoods of Oakland we had sidewalks and light poles. But I learned more about Atlanta as time went on, and the ’96 Olympics changed a lot for Atlanta. I spent four years at Clark. A lot of people do a six- or seven-year plan.

BLVR: Atlanta has a reputation for a lively night scene. So it makes sense that people would want to stay longer. Just ask Lou Williams.

MT: Lemon Pepper Lou. Atlanta’s definitely a problem, because it’s hard to go to class. Once it’s one o’ clock [in the afternoon] and it’s spring or summer, everyone’s out. At an HBCU, it’s all Black people, and we’re kicking it like the festival at Lake Merritt [in Oakland] every day. I totally understood why some people didn’t graduate on time. I even had to drop some classes and came back and finished at Laney [College, in Oakland]. At Clark, you’d see someone you know and stop and kick it on your way to class. I get how Atlanta will entice you not to finish.

BLVR: So you talked about wanting to get away from family at that point. I think many of us can relate. What was your family like, growing up?

MT: It was kind of a mess. I want to say it was a beautiful struggle, but it really wasn’t that beautiful. My family was hit pretty hard by the crack epidemic. I grew up in Sobrante Park. I was nine when my parents split. I didn’t know at the time what was going on, but it became clear that drugs were involved. Crack tore up our neighborhood. I’m talking the ’80s. I was born in ’77, so this is around ’86, ’87. I lived with my grandma, like everyone else did. Sobrante, that was the crack capital of Oakland. I remember trying to get girls to come over, and when they found out where it was, they weren’t so sure about coming. It was super impoverished.

BLVR: That’s pretty deep in East Oakland. It’s incomprehensible to me how there can be such an aggressive disparity of wealth just a few miles from the Oakland Hills.

MT: There was a time when government assistance—you know, welfare—would come on the first and the fifteenth. Then I remember they switched it to only the first. That made it really hard for us. You had to make it last for a whole month. But have you ever asked an addict to do that? There was no re-up for them. Remember that Bone Thugs song?

BLVR: “Wake up, wake up, wake up / it’s the first of the month…”

MT: Yeah. That’s what it was like. There was just people getting shot, trying to stay alive. All that type of stuff. Lights out, water out. No phone. It was typical in that sense, but it didn’t feel typical. Some people in our neighborhood had it better, and it felt like we had it worse, but come to find out as we got older, some had it worse than us. So it was time for me to get out of there. My dad didn’t really get clean till I left for college. From the time I was nine till about eighteen, that was the worst of it. That’s why I wanted to get out of there.

BLVR: How has the city changed since then? Do you ever go back to your old neighborhood?

MT: That neighborhood is mostly Mexican now, actually. Parts of Oakland are still dealing with major issues, but they’re not crack-related anymore. There’s a huge wealth disparity in Oakland. That’s a big issue. I live in West Oakland these days, still in the hood, but now I understand that there’s two Oaklands. There are diverging pathways. I went to Oakland Tech and met cool people. You felt like they were rich compared to you. Even if they weren’t. As a kid I didn’t understand this other part of Oakland that existed. But now I’m really sensitive to it all. Cars get bipped and all that. I’m not for people robbing people, but I do sympathize. Hitting up cars to survive for a few days, that would’ve been us back then too. Oakland has become an epicenter of affluence. There are million-dollar homes out here. People are doing well, but the average rent is ridiculous. There are nice restaurants, but only some of us can access that lifestyle. There’s still abjection that needs to be dealt with. In Oakland you can just go to the other side, where people are living much, much better than you. That’s what happens when you have people living in depravity. I’m in a different place now. I have a job, cars, family, all that. But I can’t forget about deep East Oakland.

III. “I WANT TO TELL A STORY FOR YOU TO REMEMBER”

BLVR: Who are some writers that influenced you early on?

MT: To be honest, it really comes from hip-hop. Coming up, I read sports every day. Sports Illustrated, the local sports pages. There was a regular column in the Chronicle that my neighbor would leave for me at the house. But that column didn’t make me want to write. Hip-hop did. I was enamored by the wordplay, the schema. Too $hort and the Dangerous Crew. I loved Goldy, Anthony Banks [Ant Banks], Ant Diddley Dog. They had a sophisticated level of how they rapped. At first, hip-hop was all East Coast. They were fast, creative, clever: Slick Rick, Big Daddy Kane, those guys. It wasn’t no bubblegum rap. When it got to the West Coast I was even more enamored. I used to debate about it all the time with friends: Who’s the best? That kind of thing.

BLVR: Who are some of your favorite rappers?

MT: In the ’90s? Yukmouth. He was crazy. His storytelling and lyricism. There was no question who was better. Same with 3X [Krazy]. You know: Keak [da Sneak], Agerman, B.A. They were lyricists. They were great. That drew me in and made me want to write. Then I went to school in Atlanta, so now you got André [3000]. He’s crazy to me. That made my writing even better. I was a big Pac fan, too, since Me Against the World. That emotion, that power. I wasn’t thinking about becoming a dope journalist. But I learned it all from what I listened to. In particular, hip-hop artists. I want you to feel what I’m saying. I want there to be turns in the way you hear a crazy line, know what I’m saying? I want to tell a story for you to remember. The way a verse starts and ends is extremely important. How do you start an article and end it? That also matters. I was indoctrinated by hip-hop, and it informs how I write, unintentionally. In hindsight it makes sense. And I was still reading Jim Murray, Gary Smith, Phil Taylor. When there was a Black writer in sports, people would point that out to me. Ralph Wiley. That was cool, but I read that for information, for sports. I was a sports nut. I wanted to understand what was going on with the Warriors and the Bulls. But it didn’t make me want to write. Ant Diddley Dog did.

BLVR: I’m embarrassed to admit I’ve never heard of Ant Diddley Dog.

MT: Bad N-Fluenz. That was a group in the ’90s affiliated with Too $hort’s label. They were a duo. Oakland dudes. At the time, it was heavy gangsta rap culture. Too $hort was hard bass, catchy lines, simple rhymes. That was his thing. And being vulgar, obviously. But Bad N-Fluenz were straight lyricists. They were hot and were about to blow up. Rappin’ Ron was a freestyler. He would rap on the bus, shouting out people and their neighborhoods from the back of the bus, incorporating it all into his raps. And Ant Diddley Dog was a straight wordsmith. That just wasn’t very common at that time [for Oakland rappers]. Fast, internal rhyme schemes. All that. They formed a duo and were affiliated with Too $hort’s label. They were going crazy. That was way before the hyphy movement. 3X came after that. Agerman actually grew up a few houses away from me, matter of fact. They talked about crazy stuff in their music, but they knew how to rap.

BLVR: That’s some real Oakland rap knowledge.

MT: That’s how I grew up. I remember going to Atlanta, and it was very East Coast at the time. The South wasn’t getting respect, either. That’s when André said, “The South got something to say” at the Source Awards. That’s around the time of Southernplayalistic[adillacmuzik], ATLiens. It was predominantly Wu-Tang, Hard Knock Life from Jay-Z. But people would say the West couldn’t rap. Cali was cool and deep but we didn’t have the same weight as New York and all that. We had to defend ourselves. Most people only knew Too $hort, N.W.A, E-40, too, but he wasn’t nationally respected like that at the time. So we played Yukmouth from the Luniz and Ant Diddley Dog to show them we could rap. Y’all think we can’t rap in the Bay? Here, put this on. That was our argument. This was during the whole East versus West battle. Rappers helped us defend our culture. They were lyrical.

IV. BROCCOLI AND BASKETBALL

BLVR: You’ve authored a few seminal biographies of NBA megastars like Stephen Curry and Kevin Durant. How do you approach writing about the life of an athlete, as opposed to a single game?

MT: Those books were two such different processes. They were both incredibly difficult, if I’m being real. There was a limit on access. The short story is this: I didn’t even know how to do it, but I did it. You look back and you’re like, Man, I really did that. For Steph, I had the benefit of having covered him his entire career. I got the book deal in 2016, when they went twenty-four to zero. I signed the book deal in January. But I’d already known him for so long that I didn’t really need too much by way of access. The book was initially going to be about the Warriors season: seventy-three wins, historic year. All that. But things changed.

BLVR: Three to one. Three to one. I’ll never forget those finals against Cleveland.

MT: Man. Once Kyrie [Irving] hit that shot, it changed everything. I had to switch up thousands of words.

BLVR: So you were working on the book during the whole season? Did you ever get to pick Steph’s brain about any of it?

MT: Steph was a participant, but I didn’t have to do any interviews with him about the book in particular. I could just ask my questions as a reporter. I was telling a story that wasn’t over. We didn’t know the end of it, because it was happening live. It’s not like Steph was answering questions about the book while he was competing in the playoffs. They had a job, I had a job. It’s so different, dramatically, from writing articles. My arrogance as a writer made me think I could just write all day, no problem. But I realized it’s completely different. I had to learn how to write a book and not shorter articles. And they only gave me six months. They wanted it in July. I was ignorant and didn’t know what it would be like. It turned out to be ridiculous. Eighty thousand words in six months of a constantly evolving story. I’m tracking the season and suddenly it’s all gone, once they didn’t win that title. I got maybe three weeks left. I’m in a Starbucks, trying to finish. Then the team signs KD. It was grueling, and I knew it wouldn’t end. I went the route of penny-pinching questions throughout the course of the season, as I needed them. I also tracked down family, coaches, things like that. But I’d known Steph for many years, so I knew his story and was lucky in that aspect.

BLVR: How do you get NBA players to open up?

MT: To be honest, there aren’t any shortcuts or tricks. The easiest way is the same way you get anyone to open up. Just treat them like people. They’re individuals, so each approach isn’t universal. You don’t have to do much to get Draymond [Green] to open up. He just opens up. That’s him. And once you put in the years and accrue that time, you know them and they know you. I try to be me, and whoever I am, if that vibes with them, I’m OK with that. If not, that’s OK. There’s a lot of people I don’t vibe with. That’s OK. Other media people with other personalities might get those people to open up and I might not. Some people require commonality; some people require rapport outside of basketball interviews; some people respect how you talk about the game. KD was like that. He enjoyed that: nerding out on basketball. But KD would also talk to me about broccoli. He just likes talking to people. Klay [Thompson] is cool, but he’s different. He doesn’t talk much. That’s my guy, but he’s just not a big talker. You have to understand that.

BLVR: I covered an NBA game this season and the press room was intense. Mind you, I’m not a sportswriter—I’m coming from the world of food and culture reporting—but it felt noticeably cutthroat. I had nothing to ask Jimmy Butler in a room full of reporters already asking him rapid-fire questions.

MT: My approach is to vibe with that intensity. I like to be contrarian and catch people off guard. Keep them on their toes, be funny. When I’m asking a question, I don’t want a canned answer. Or I don’t want them to be like, Here go Marcus again. Since they know me, I might go left or I might go right, and it’s often based on inside jokes. It’s different. That’s built behind the scenes. It’s easier to pull off when you’ve been doing it for a while. That Wardell situation, when I called [Steph Curry] Wardell? That was on the spot. They can’t really see who we are. All they know is someone is talking, and you gotta be like, Steph, over here. I wanted to say something to let him know it was Marcus. It breaks the monotony. When I said “Wardell” he knew who it was. Steph still gives me a hard time for that sometimes. But I can throw it back at him.

BLVR: What do you think about the whole “old media” versus “new media” narrative? A few current and former players in the NBA, including Draymond, have been creating their own platforms and claiming that traditional journalists aren’t worth their salt.

MT: I’m not really worrying about it. I don’t think it’s actually a problem between old media and new media. I think it’s good media and bad media. That’s the issue. I think it’s hard to recognize from the players’ perspective, because media is a varied field. Not all of us are on [ESPN’s] First Take. Things that new media says they’re doing are already being done by great journalists across the nation—but they’re not usually the ones you see on TV.

When I was coming up, old media versus new media meant print or digital. The focus wasn’t on how the media operated; it was about the technology shift. Old media had to turn in the story when the buzzer sounded, to make a print deadline. New media could be filing a story at 5 a.m. or later, because sometimes it doesn’t really matter, depending on the story. You can develop a story after the buzzer and don’t always have to rush it for the newspaper trucks. That was the dichotomy I remember with old and new media. But what players are talking about now is more the difference between bad and good media. They point out things that the media does poorly, which they’re not wrong about. I consider myself new media because I write for digital platforms. I used to be old media on print platforms. When they say good media does x, y, z, I think I do that. I write about basketball, not drama—unless the drama noticeably impacts the basketball. We go to the sources and we ask what’s up instead of lobbing shots from afar. I would argue there’s plenty of people in this space doing good media. With honesty, with integrity, trying their best. But they’re just not on whatever show those players are watching and getting irritated by.

BLVR: Social media definitely doesn’t help with that hysteria.

MT: Let’s not act like the drama don’t benefit everybody, though. Look, I have plenty of issues with the larger landscape of media. But the fans are very clear on what they want. You can write the greatest play breakdown of all time, but it don’t hit like a rumor will. Know what I’m saying? We write so many articles a year. You can just look at the data. If you write a great analysis of a trade or someone’s basketball abilities, you’ll learn a lot from reading it. But then you write about a rumor, and fans make it very clear which one you should write more of. People like me, who are at a point in their career when they can take Ls, don’t have to go viral. I’m not chasing those stories. I can take my time to write about assistant coaches and player profiles. That’s my thing. But I can make that sacrifice. Part of media is giving people what they want. It’s a catch-22. You gotta keep the lights on.

BLVR: OK, to wrap up here, do you have any advice for Oakland’s youth, particularly those who might want to develop and share their voice, like you have?

MT: My advice is to know your worth. Your inherent worth, your accumulated worth, and your situational worth. It is likely greater than you suspect, than you imagine. If you understand your value, that should be your greatest pursuit—understand how immensely important and valuable you are. If you don’t know it, others will dictate it to you. If you don’t believe it, no one else will. Worth is not about finances, although you should understand what you’re worth from that perspective as well. Your perspective has value. Your experience has value. Your talent has value. Your intangibles have value. Your beliefs have value. Your personality has value. Your dreams have value. Your being has value.