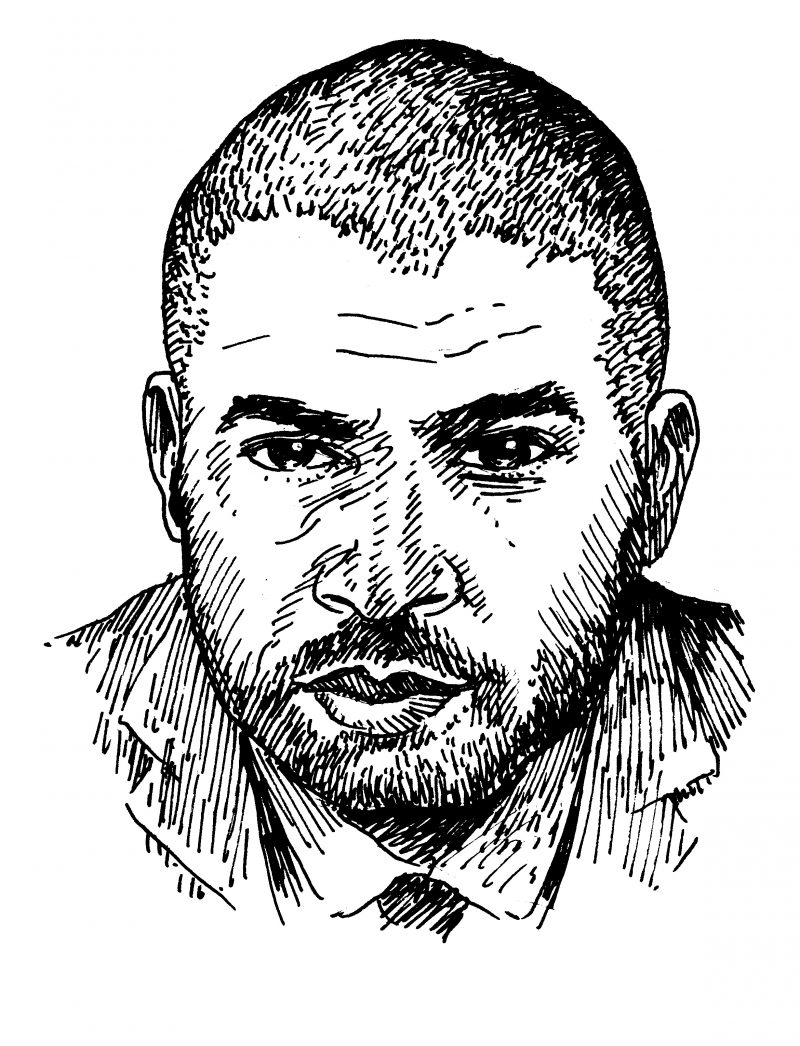

Jason Moran is cutting a wide path for jazz in the twenty-first century. He embraces tradition and courts innovation, joining the past and the future. He’s reinterpreted works by one of his musical forefathers, Thelonious Monk (whom he calls “the most important musician. Period.”), but he also regularly pushes the boundaries of improvisation, performing with dancers, filmmakers, painters, and writers. He’s astonishingly prolific, making records as a bandleader, soloist, guest artist, and with his longtime trio, the Bandwagon.

As an educator at the New England Conservatory and as a musical curator, he’s creating a new context for jazz. Recently, he created a concert series at the Park Avenue Armory, featuring musicians who exist at the edges of the mostly conservative jazz world, including Alvin Curran, Charlemagne Palestine, and Matana Roberts. In 2010, he won a MacArthur Fellowship for “genre-crossing performances.” In 2014, he was named the Kennedy Center’s artistic director for jazz, perhaps the most significant international title for a jazz musician. That same year, he scored his first film (Selma) and recently composed his first orchestral work, which premiered at the San Francisco Symphony in May 2018. Like Miles Davis did before him, Moran aims to influence the direction of music both through his musical language and the dynamic community with which he surrounds himself.

Moran also makes visual work. While jazz is not usually considered a visual medium, Moran merges its musical vocabulary with the fresh, experimental context of contemporary art. He’s spent much of his career collaborating with some of the most significant visual artists of the last half century, including Adrian Piper, Glenn Ligon, Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, Kara Walker, and Julie Mehretu. At the 2012 Whitney Biennial, he and his wife, opera singer Alicia Hall Moran, created a five-day hybrid performance of artistic disciples in a single space. At the 2015 Venice Biennale, he exhibited a sculptural re-creation of Harlem’s historic Savoy Ballroom stage. In May 2018, Moran presented his first solo museum exhibition at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, which included three re-created stages (including the Savoy’s) and a series of his charcoal drawings, which he makes by taping a piece of paper over the piano, covering his fingertips in charcoal, and playing.

I spoke with Moran in New York, a few days after he’d returned from a London performance with Joan Jonas, his longtime collaborator and one of the indisputable pioneers of performance art.

—Ross Simonini

I. “WHEN THE MUSICIAN STEPS OFF THE STAGE, WHAT DO THEY BECOME?”

THE BELIEVER: You’ve been working with Joan Jonas for about fourteen years. What’s the process of that collaboration?

JASON MORAN: Our relationship started kind of… she’d sit me at a piano, and then she’d turn on the screen, the projector, and then she’d show clips and videos that she was in the middle of editing. And then she’d talk about what the piece is about or start reading the text that she was also pulling away from a book or a novel, and then I would just start responding. And it would really just go on for hours. I mean, we’d do eight hours a day, Monday through Friday, going through all of this stuff. And every once in a while I would hit on something good, and she’d say, “OK, what’s that right there? What is that sound? Can I hear that some more?” And then we’d find all our themes.

BLVR: You’re improvising from a visual cue rather than from a fake book or a melody. How does that work? Pure intuition?

JM: I grew up in a house where my parents collected a lot of art. So I’d literally be practicing, you know, a McCoy [Tyner] kind of solo but staring into a painting, or pottery that was underneath the piano. There was a way of connecting those two visuals. I don’t have synesthesia. So how does a painter give an object a shadow? So how does a melody have a shadow? Do you know what I mean? It’s simple things like that also. How do you create a shadow off of a… You know, do you use reverb? Do you consider reverb the shadow? What other kinds of ways of making a shadow [are there]? Or make something reflective: how do you make something reflective in music? Those are the kinds of things that I’m drawn to, and also how artists talk about how they create their work. For me, it’s become a major part of how I work. I’m finding the way that music can work in the same way that negative space works for a sculpture.

BLVR: Is your work received differently in the art and music worlds?

JM: I’ve always thought that there wasn’t as far a stretch [between the art and music worlds] as I might have imagined. I think from the collaborations that I’ve done not only with the musicians but [also] the artists or the writers or the choreographers or filmmakers, [I’ve learned] that what musicians look for, especially jazz musicians, is a way to communicate, and they wanna do that in a way that seems like people around them are listening. Like actually listening, not tuning you out. I think every collaborator is looking for that, too, whether they work in the same field or not. I think the work that I make now is also just really in a lot of ways still a reflection of the people I’ve been working with.

There’s a way that people look at history, you know; there’s a way that people kind of find their way of manipulating the material in history. And in jazz that is what I had been doing: just simply making my record. How do you look at history, and what aspects of it do you want to make your audience aware of? Maybe within the museum show, I think that the way that jazz is discussed, both its positives and its negatives, are things that we can think about. So when the musician steps off the stage, what do they become? What does the stage look like when there’s no musician on it? As a space in itself? I felt like what I was learning about was the stage and what these historic jazz venues have brought us. They’ve created an environment for freedom to be addressed on a very small platform, and we should look at those platforms that this work happened in. Because it’s not simply about the musicians. It’s about the space that surrounds them. It’s about the time.

BLVR: Is there a history of this kind of crossover with jazz and visual art?

JM: I mean, there’s a history of communities living together, like David Hammons and all of his friends: the composer Butch Morris, Henry Threadgill—they have long relationships together. The trombonist George Lewis and the work that he’s done with Stan Douglas, maybe twenty years ago. But I’m talking about one school of musicians right now, and I might consider myself a grandson of that school. It’s a group called the AACM, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. It was started in Chicago by one of my teachers, the pianist Muhal Richard Abrams. And they would do performances all the time—this performance-art-hybrid-theater-compositional kind of thing. And so, you know, I’m from that.

And I have this kind of myth about the way that the Harlem Renaissance was working—that, you know, people like Zora Neale Hurston knew Langston Hughes, and they knew Duke Ellington and Mary Lou Williams… People knew each other and people were in contact with each other and each other’s process, and that was why the work was so great. So whether it would blend these things was not the point. [The point] was that you had conversations that informed your own work and made it more potent, because it had the layers that would sustain through history, as we now understand when we look back at them.

For myself, I wanted to have a relationship with various types of artists like that. The Studio Museum in Harlem has been kind of a great resource in that way, because it’s the local museum for me, as a Harlem resident, and what [director and chief curator] Thelma Golden also promotes, having artists know each other. It’s community-building.

II. “A WEIRD KINDA DISNEYLAND”

BLVR: Do you try to maintain a balance between your roles as artist and curator?

JM: I don’t think that an artist has balance. The reason that they’re an artist is ’cause they can’t control their balance. They’ve put every moment on this canvas or into the work… They don’t have a cutoff; there’s no clock-in, clock-out. If you have a family, all this stuff gets very muddy, but the desire to create can’t be measured. So you just continue. You continue to find ways for the work to have some sense—at least for me—to have some sense of value, not only to what I need to do but also to the people around me, so collaboration becomes kind of perfect for it.

I’m very aware of where my cutoff is. Meaning I know where my weak points are within my own craft, but from a curatorial mind, it’s like, OK, so find the other people who do all that other stuff that you love, that you wish you could do, and invite them to make something.

BLVR: You’ve often talked about Thelonious Monk as a musical father, but looking at your work, I think a lot about Miles Davis’s ability to cultivate communities.

JM: Yeah, what’s always the curious thing about Miles Davis is that he was able to have these seminal bands and totally just leave them. [Laughs] It’s so rude! He’s a very peculiar case within jazz tradition, because at many points people who were jazz enthusiasts became frustrated with how he was working, because he kept moving forward. And of course by the end of his life, you know, the stuff that he was trying to figure out with hip-hop was just his last stop, ’cause he knew that that was where the future was going… He always had his ear somewhere. I remember seeing an interview with him, when I was young, on The Arsenio Hall Show, and he talked about going to a Los Angeles Lakers game, and he talked about listening to the sound of the ball hitting the ground and the screeching of the sneakers on the floor, and he thought that that was composition. I’ll never forget hearing him say that on national TV, you know, because in that moment he might have been considered the weird artist who hears all kinds of strange things and finds beauty in it. But hearing him say that on television as a young kid was like a marker for things that I should be listening for in the future.

BLVR: It’s funny that you say that, because I remember a seminal moment for me was when I heard Miles talking about listening to a door creak and a chair squeak and finding the interval between the pitches. After that, I was always trying to become that sensitive.

JM: And that’s the artist’s fault, you know, that [they] can’t help but notice these things, and there are worse problems in the world, but [laughs] it’s the thing we can’t turn off.

BLVR: The set is an important term in your work. What’s that about?

JM: Yeah, well, you know, the set is two things. The set is the space, the stage, and then the set is the collection of songs. The way that I work with the set—and specifically the set list for my band—is I don’t create the set list until I’m in the space and we start playing. And then as it’s occurring we decide which songs go next. But only as that moment occurs after the applause. That kind of space where we aren’t sure which direction we decide to take the audience in, do we just burn their ear out now, or do we give them a place of rest? These things happen on the set within the set. And that, you know, is what I think that center speaks to.

BLVR: But then also they’re referring to it as the set that you’re sort of reproducing in the space, right?

JM: Well, yeah, that’s all about where we are.

BLVR: The word set suggests a kind of theatrical experience, a place of dreaming.

JM: There’s a quote from Mies van der Rohe about going to the Savoy Ballroom and being overtaken by what the stage looked like, this kind of art behind the band. And he said how stunning it was but also that he saw, projected onto the stage, clouds. Now, I don’t know whether or not he was smoking or whether there was a lot of smoke in the room, or whether it was an actual projector projecting clouds onto the band, but it’s how I like to hear about the rooms that I play in, you know, like how to describe these places beyond the music that happens within them.

The Village Vanguard, on Seventh Avenue just off of Eleventh Street, has a basement room. The reason music is powerful in that room is because of the shape of the room and the relationship the audience has to the band. And those things feed each other, so all the recordings that have happened in that room are also really documenting what happens in the room, how the room is shaped, how the audience feels in relationship to the music. All that stuff is resonant in a recording, but as a musician, when I’m listening to the recording, I’m only listening to, OK, what does the band do? And that invisible part is those stages.

In America, in history, when buildings are torn down that have kind of cultural prominence or value, this is also a problem. So having them, those stages now [at the Walker Art Center] that are in close relationship to each other when they’ll be in this gallery space together, it’s kind of a weird kinda Disneyland.

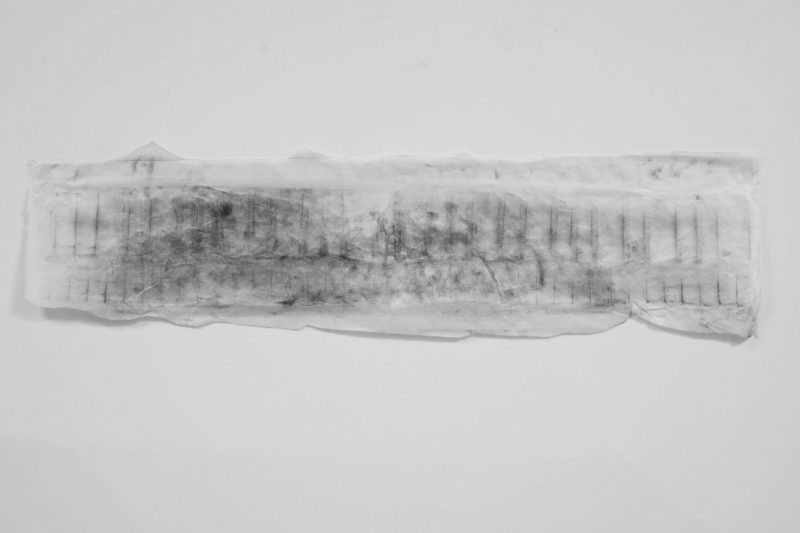

BLVR: Your other visual works, the Run drawings, are a kind of process art. Is that how you see them?

JM: Yeah, exactly. Like, where does the residue lie in a performance? In a sonic performance, if you’re staring at a piano keyboard, not anticipating that a person’s hands have left all kinds of residue on it that is visible, let alone the emotional content of some of those notes as well, how does that show up? Learning about this kind of process, in [Joan Jonas’s] performances, these kind of quick drawings—sometimes she’ll do a quick succession of a bird, or a fish, or a snowflake. So what are the gestures that it makes? Having the residue left on paper, it’s kind of a time stamp, but also the evidence that it happened.

It’s really… destroying a piano. [Laughs] Meaning, like, ’cause it gets really dirty. But I love this kind of tough paper that also is fragile enough to break a little bit, and it’s paved onto the piano and my hand is dipped in all this dust, and then I start playing. And then where the dust finds gravity, whether it’s the pressure of my finger or when it falls away from the paper, it’s the trace that it leaves.

BLVR: Did you draw when you were younger?

JM: Privately, yeah.

BLVR: But these drawings are the only kind of handmade objects you’ve really ever shown?

JM: Right.

III. COMPOSITION IS THE DIVING BOARD. IMPROVISATION IS THE SWIM

BLVR: Do you always write music at the piano?

JM: I really depend on the piano as a mirror, so I generally do write at the piano. The peak times I’ve written pieces, they were based simply off of equations that I would learn from Muhal Richard Abrams. But yeah, most things start at the piano.

BLVR: What do you mean by “equations”?

JM: Well, he had this system of composition called the Schillinger System of Musical Composition, and one of the first ideas presented in his two-volume book [by that title] is that there’s no music unless there’s rhythm, and so we must understand rhythm first.

So he’d break out graph paper and then you’d start to work through these equations, which kind of more were like collections of beats. So let’s say six times five is thirty, and then you’d break up one melody into six, one melody into five, one melody into the entire thirty beats. But then you’d distribute those notes kind of anywhere you wanted to, or it made, like, a certain kind of system of only two notes in one direction, or you can have no more than three notes more than a second apart in a row. And once you’d set that up on the piano, it would sound—to me, it would sound nothing like I’d ever compose if I started at the piano, and this was a way of moving away from harmony that I thought was interesting.

BLVR: There is this kind of inherent visual grounding in a lot of music. I think it’s impossible to not acknowledge the look of the graph paper or notes, the keys of the piano, the neck of a guitar.

JM: Yeah, spacing and density. There’s such an obvious part about learning music that leads us to think that the only way to read music is from the top left corner to the bottom right, but that’s only one of many ways. So if you gave that to a child and they didn’t know that they were supposed to do that, they would absolutely try things that maybe you hadn’t considered, and that would then reveal another notion of what the music was.

You know, I was talking earlier about, say, negative space in composition, like looking at the sculptures of Rachel Whiteread. She had me readdress the way that I would play some of Monk’s music. Like let me actually apply some of what I think I feel in her work to how I play Thelonious Monk’s music. Because I can’t just play his music. There needs to be another kind of thought process that would help me leapfrog some of the traps of playing Thelonious Monk’s music, because it is so pianistic, and for many people it’s hard to break away from his style of piano playing when they play his music. How can I do that? And Whiteread kind of showed a way of thinking about negative spaces in his compositions. So these are things that I’ve built into how I write. It doesn’t solve all the problems, but it gives me options.

BLVR: So you feel that there’s a distinction between composition and improvisation, or is composition just frozen improvisation?

JM: Well, within the improv world, we think of composition as the diving board, and the improvisation is the swim. And then we climb back out and we dive again. You know what I mean? But we use the composition to kind of launch ourselves, rather than it being the only destination. I mean, all of the music then becomes the composition, but the swim—you know, kind of maneuvering in the water—is how composition fits with my jazz practice.

When you hear a really great composition by [György] Ligeti, the way that those piano interludes work, they flow in a way that my favorite improvisers also flow, so there’s an inherent logic that you feel with really great composition. These are all things that I’ve felt also in working with a band. Sometimes you play with them and sometimes you go against them, and great pieces of music just tend to do this, whether we knew that it was written down or if it was improvised.

BLVR: It’s almost like you’re talking about composition as a screenplay or a blueprint.

JM: Right, and it really depends on everyone else in the room, or in the band, to kind of bring it to life, and as composers, [we have to let go] of some of the things we have in our minds.

BLVR: You’re about to work with San Francisco Ballet, which must be the opposite kind of experience. All notated.

JM: The choreographer Alonzo King and I have been working together maybe six or seven years, maybe longer—maybe ten years; I don’t know. But this is the third piece I’ve written for something that he’s choreographed, and it’s the first time that it’ll be done. He’s working with San Francisco Ballet, and he asked for an orchestral piece, so I wrote an orchestral piece about twenty-five minutes long. A little nervous about that.

BLVR: Will you be playing with the orchestra?

JM: No, I wanna sit in the audience. I think as a real composer they would sit in the audience and hear it. [Laughs] I’m looking forward to hearing it. It’s not really built around the piano, either; it’s really built around an orchestra.

BLVR: And this is the first orchestral piece you’ve written?

JM: I mean, I wrote a film score [for Selma] that was for orchestra as well, but, you know, a film score’s very different.

BLVR: Film scoring is making music in a larger context of images and actors and story. That’s so in line with your method. But it’s such a different way to think about music than performing a solo piano concert.

JM: Looking at jazz history, in the ’20s musicians got rid of all the dancers that were around, the big suits, the choreography, the stage elements. So by the time it gets to the ’40s it’s just Charlie Parker in the little basement club. It became more personal, about the person. And it kind of continues along that path of being here in a room with my ideas, singing or playing these songs, like a voice recital. And that stuff is scary.

When I go play solo piano concerts, I know very much that it’s the ultimate challenge. This is for the win, right here. [Laughs] It takes a certain kind of focus. And also you know the things that I’ve learned from working with all these people we’ve been talking about is that those extra elements still do come into play: the lights or the approach to the instrument still come into play, just as it does for a choreographer in a dance company. I mean, I’ve been to see enough solo recitals at Carnegie Hall to know that when there’s just nothing else in the room, when great music takes over a space and puts an audience in a trance—that’s gold.