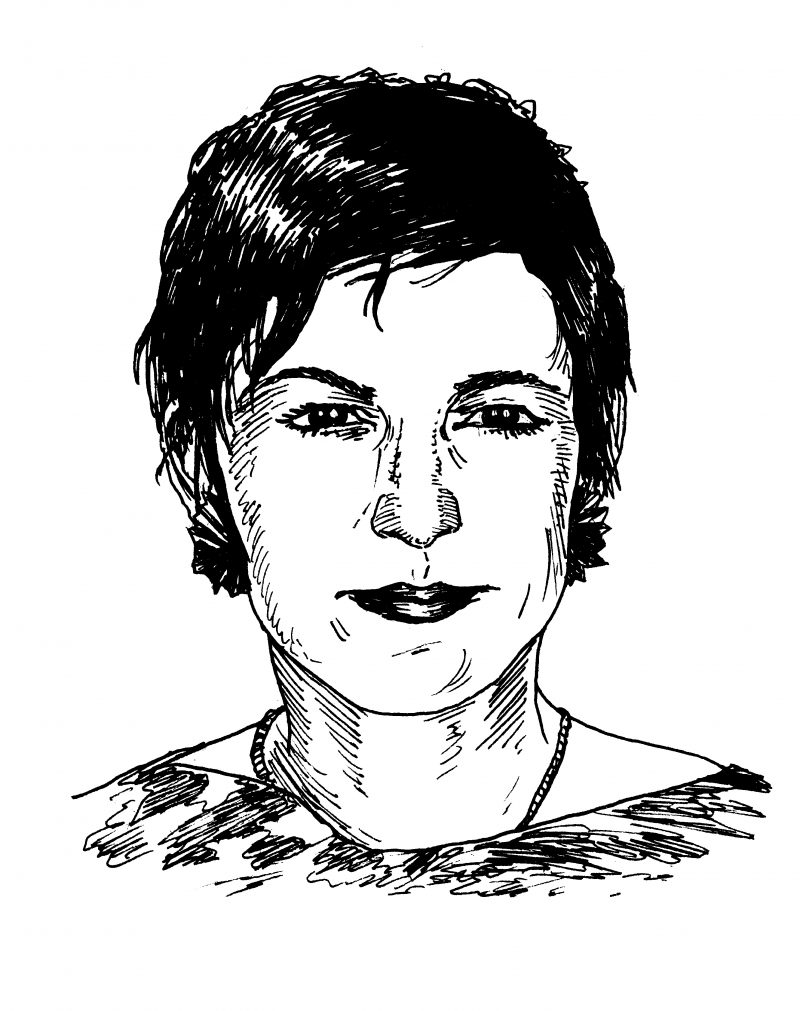

Elizabeth Peyton, born in 1965, is an American painter whose intimate portraits of her friends and heroes respond to an era in which our peers and icons seamlessly coexist. Prince Ludwig II, Kurt Cobain, and an eight-year-old Eminem are given the same special treatment in her work as politicians, friends, and partners. This makes it easy to see whom she admires, but I’ve always wondered why. The work goes beyond fandom and approaches something closer to devotion. I was curious about what she believes in.

I was a little nervous about interviewing Peyton because, ever since seeing her work in a small MoMA show on figurative painting in 1997, alongside that of Luc Tuymans and John Currin, I have counted her (and Tuymans) as a hero of my own—and you know what they say about meeting your heroes.

Since that show, Peyton’s artist books, paintings, and drawings have never failed to move me. Her use of paint is juicy and there is physical energy and raw emotion evident in her panels. To me, her pictures carry the seductive impulse that compels you to rip an image out of a magazine. They have the sincerity of a love song and the spirit of punk. I admire and try to emulate the courage she has to wade right into her obsessions and attractions and turn them into art.

We both live in the West Village in New York, and decided to do the interview at a nearby café. When Peyton arrived she was smiling and holding a new album by the Danish band Vår. We spoke about talented Danes, then got down to the business at hand.

—Leanne Shapton

THE BELIEVER: You’ve done so many interviews—

ELIZABETH PEYTON: Really? I don’t do them that often, maybe a couple times a year. I feel like while I’m alive it’s good for me to speak up for my work, because how I feel about my work and how I see it are so different from how I see it reflected back to me in other writing. So I feel like, while I can, even if I don’t love doing it, it’s good for me to talk. Even though I do feel strongly that the work should really speak for itself, and it does, and it will. But I think that clichés can happen and I think that people read stuff on the internet that so endlessly self-perpetuates.

BLVR: There are a few things I wanted to talk about today. Something that is on my mind a lot is photogenics, or photogenesis, if that is even a word. How people look in photographs versus how they look in life.

EP: I suppose I think about the photo thing quite a lot—I don’t think about it, but...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in