Donald Hall wrote his first poem, “The End of All,” at age twelve, while under the spell of Edgar Allan Poe. Through the years his retelling of it has varied, but the gist is:

Have you ever thought / Of the nearness of death to you? / It follows you through the day, / It screams through the night / Until that moment when, / In monotones loud, / Death calls your name / Then, then comes the end of all.

Mortality is a theme Hall has stuck to for seven decades. Open a book of his poems or essays at random and plop down a finger, and chances are you’ll land on some combination of death, grief, interment, loss, and the humiliation of aging—in other words, the long, haunting slide into the grave. Even when his work is not explicitly about death, its world and the things in it are frail or in danger of disappearing for-ever: a beloved dog or farm horse, apples plucked from a tree, a childhood memory, an old love. In 1955’s “My Son My Executioner,” the otherwise happy occasion of a newborn child manages to put steel in Hall’s spine: “Sweet death, small son, our instrument / Of immortality, / Your cries and hungers document / Our bodily decay.”

But Hall can also be funny, especially about his own death, as in his essay collection Essays after Eighty (2014): “It’s almost relaxing to know I’ll die fairly soon, as it’s a comfort not to obsess about my next orgasm.” Ambition has passed him by. “My goal in life is making it to the bathroom.”

Hall is the Homer of the ordinary doozies that we rarely notice: “We ate, and talked, and went to bed / And slept. It was a miracle” (from “Summer Kitchen”). There’s also the Red Sox, the joys of solitude and farm life, of breakfast and evening snowfall and afternoon romps in the sack, of smoky views of Mount Kearsarge—all of the small adventures in domes-tic tranquility.

Hall grew up in Hamden, Connecticut, and spent summers at the family’s Eagle Pond Farm in Wilmot, New Hamp-shire. He attended Harvard with some heavies of midcentury American letters: Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, John Ashbery, Robert Bly, and, down the road at Radcliffe, Adrienne Rich. Later, he became poetry editor of The Paris Review during its formative years. (A rejected Allen Ginsberg complained to George Plimpton that Hall “wouldn’t know a poem if it buggered [him] in broad daylight.”)

In 1957, Hall joined the English faculty at the University of Michigan and, by his account, was that rare species of writer who actually enjoyed teaching. He put in seventeen years before bailing on academia and retreating with his wife and former student, the poet Jane Kenyon, to Eagle Pond Farm, where he’s lived ever since. Nearly two decades later, Kenyon died of leukemia.

With occasional lags, Hall’s literary output has been relent-less: more than fifty books, including twenty-five volumes of poetry (his book-length poem, The One Day, won the 1988 National Book Critics Circle Award), two essay collections, seven memoirs, fourteen children’s books, and a wonderfully strange biography of Dock Ellis, the baseball player who pitched a no-hitter on LSD.

Now eighty-nine, Hall has quit writing poetry, finding that it requires too much testosterone and frontal-lobe work. His energy goes into essays. In July 2018, he’ll publish a new collection called, appropriately, A Carnival of Losses: Notes Nearing Ninety, which, when this interview began, he doubted he’d live long enough to finish.

Our interview came at a bad time. Hall had just gotten home from the hospital, where he’d been admitted for congestive heart failure. He was understandably pooped and begged off speaking by phone: “I’m no good on the telephone. My IQ loses half its numbers.” So I’d email him a bunch of questions, he’d chew on them for a while and dictate responses to his assistant, who’d email them back. “You then make new questions, extend old ones, ask new ones out of my answers,” Hall wrote to me, “and within a year we have a whole interview!” Actually, it took only two months.

—John O’Connor

I. “THE LOVES OF MY YOUNG LIFE WERE GRANDFATHERS.”

THE BELIEVER: I hate to start on a down note, but I understand you were recently in the hospital. How are you feeling?

DONALD HALL: I was in the hospital twice in February 2016, and when I came home I had 24-7 care. Not for long. I did not need it, and found it annoying. Doctors had diagnosed me with congestive heart failure. I feel better now than I have felt in a couple of years, stronger and more ambitious. I was quite sure that I would die. I won’t, just now.

BLVR: I’m glad to hear it. This isn’t the first time you’ve come back from the edge.

DH: When I lost half of my liver in 1992, I was told I had a 30 percent chance of surviving the next five years. Jane and I both knew for sure that I would die. She bought a massage table and tried to rub the cancer out every day. I got better. She got leukemia.

BLVR: Are you able to write?

DH: I could not write anything for many months, and I thought I would never write again. Now I am writing prose every day. I had written every day since I was fourteen, so it was depressing to stop. I write longhand and my cryptanalyst, Kendel Currier, types it up for me. I revise it again in longhand. And again. I’m working on a book of brief prose paragraphs, observations, and stories that I remember—in the manner of Essays after Eighty. It’ll probably be a posthumous publication. I’ve only done twenty thousand words or so.

BLVR: You’re no longer writing poetry—“Not enough testosterone,” you’ve said—but you think that writing prose is a different ballgame: “I’ve always felt that poetry was particularly erotic, more than prose was.” I know some prose writers who might find that emasculating. What exactly does poetry tap into for you that prose doesn’t?

DH: My doorway into poetry is its sound. It is rhythm, in line breaks and sentence structure, and in adjacent diphthongs that please the erotic mouth. In prose, rhythm and sentence structure contribute to expression, but the sound is less controlled, less effective. Sitting in a chair, silently reading somebody else’s good poems, my throat gets tired, my mouth exhausted.

BLVR: Matthew Arnold also stopped writing poetry in favor of prose, but in his mid-forties. Do you think every poet hits the wall sooner or later?

DH: If you live long enough, yes, everyone does—except for Thomas Hardy. With a young poet like Keats, death is the wall. A younger poet friend of mine insists that nobody should be allowed to write a poem after eighty.

BLVR: Do you miss poetry?

DH: Yep! But less than I might have thought, because the prose I write satisfies me more than I would have thought. I had assumed that compared to poetry, prose would bore me.

BLVR: You’ve been referred to as a “plainspoken” and “rural” poet. What do you think this means, and do you consider it a compliment?

DH: Well, I’m “rural” in many poems, I suppose. “Plainspoken” with my diphthongs? I have been called “Farmer Don” in a book review. When I read my poems aloud, I concentrate so much on sound that I feel more sensual than plain. So I think.

BLVR: Why do you think you’re so attuned to sound?

DH: Poe was my first poet. I would no longer think of his sound as satisfactory—but Poe certainly paid attention to it.

BLVR: You write in your memoir Unpacking the Boxes that much of your poetry is elegiac, even morbid. From the very start you had a Keatsian sense of impending mortality. Is it possible to say why you were drawn to the themes of death and decay, and why you’ve stuck with them so relentlessly?

DH: The loves of my young life were grandfathers and practically anybody old. Of course, old might be the sixties. Extreme old age might have frightened me, but a love of relatively old people—who were apt to die on me—was always there. When I was twelve or thirteen, a bunch of great aunts and great uncles died. Funeral after funeral. I lay awake at night, twelve years old, saying to myself, “Death has become a reality.” My first poem, at twelve, was inspired by Poe, and began, “Have you ever thought / Of the nearness of death to you?”

BLVR: There’s an epigraph in your book-length poem, The One Day, from Nadezhda Mandelstam: “Poetry is preparation for death.” Does poetry help us reckon with death? DH: I’m not sure. Poetry uncovers the journey. As I said in an essay, “There is only one road.”

II. THE GRAVESIAN NAP

BLVR: In Essays after Eighty, you describe an encounter you had with a security guard at the National Portrait Gallery who, seeing you in a wheelchair, talked baby talk to you. “When we turn eighty,” you write, “we understand that we are extraterrestrial.” Why do you think the very old get culturally shouldered aside, or condescended to, or worse?

DH: I suspect there is a fear of approaching death. I remember in my sixties and seventies feeling alienated from people who moved into their eighties or nineties.

BLVR: When you and Jane moved to Eagle Pond Farm in 1975, were either of you worried that you wouldn’t be able to hack it as either freelance writers or country people? Was there any trepidation or regret at leaving Ann Arbor and university life?

DH: We loved the notion of changing from the academic cock-tail party world to the silence and solitude of the country. I had taken Jane here on a visit—I think three years in a row—and she adored it. I wasn’t surprised. She had never left Michigan, aside from one brief trip to Vermont, but when she was first my student I called her “New England Jane.” Back in Ann Arbor we had thought of moving from our house in town to a place in the country. Once we were driving, looking outside Ann Arbor, and Jane said, “Why are we looking here when there is New Hampshire?” It would have been a long commute! Obviously she liked the idea of moving here. I always wrote every day, even while teaching, and I enjoyed teaching—but writing all the time was glorious. The move was the smartest thing I ever did.

BLVR: Does the quiet life have any drawbacks? Does boredom ever set in, or loneliness?

DH: As Marianne Moore observes, there is a difference between solitude and loneliness. I love solitude, and loneliness is painful.

BLVR: Did you always know you’d move to the farm? Or, more to the point, did you always imagine a life of solitude for yourself?

DH: I always wanted to live on the farm, but until my marriage to Jane I never thought it was possible. I never thought of living here alone. Jane gave me the courage to forgo the cradle-to-grave academic life. Her parents were freelance musicians, so the move was less frightening for her. I was terrified about making a living.

BLVR: Wasn’t it Robert Graves who planted the seed that you could make it as a freelance writer?

DH: Robert Graves asked me if I had tried going freelance, which was a good point—and helped to start me thinking more about it.

BLVR: I believe Graves also taught you the art of the nap, which in his mind wasn’t purely restorative. He told The Paris Review that “sleep has seven levels, topmost of which is the poetic trance—in it you still have access to conscious thought while keeping in touch with dream… No poem is worth anything unless it starts from a poetic trance.” Was he full of it? Did your poems start from the “poetic trance”?

DH: My Gravesian naps were not trances, no. But twenty minutes asleep and I woke full of energy.

BLVR: Solitude and separateness, being an outsider, are recur-ring themes of yours—you’ve called your marriage to Jane a “double solitude” in which you both were selfishly protective of your work. Can you say why separation is so vital? Does physical isolation enhance the work?

DH: I was an only child, like many of us born in the Depression. I didn’t like other children—and I spent a lot of time alone. Later, in Ann Arbor, I enjoyed the cocktail parties because my first marriage went bad. After divorce, when I married Jane, the same parties interrupted our intimacy. Our double solitude concentrated on our work and our inwardness and our companionship.

III. “DOUBTLESS, COITUS INTERRUPTED MY SUFFERING.”

BLVR: In your memoir Life Work, your ninety-year-old grand-father tells you his secret to life: “Keep your health—and work, work, work” (or in his voice, “woik, woik, woik”). You’ve followed his advice, at one point publishing, by your estimation, “at least one item, from a book review to a whole book, every week of every year.” What do you think has driven this output?

DH: I have always loved work! My first wife had no interest in poetry. My obsession with poetry was a distance between us. Here, with Jane, I got up at five and worked twelve hours in a day. I worked on Christmas Day in order to be able to brag that I worked on Christmas Day. My schedule lapsed with Jane’s death. Now I get up at about 7 a.m., dictate letters and work on prose, and lie down at about 10:30 a.m. In the afternoon, more of the same. It’s revision I love the most. Everything is a problem to be solved. The solution is joy. Some of the essays in Essays after Eighty took eighty-five drafts. Bliss!

BLVR: You’ve said: “The process is discovering by revision, uncovering by persistence. I revise more than I write. I have no idea of my identity, writing or revising, certainly have no idea of an audience.” Before I read this quote I had wanted to ask who your imagined audience is.

DH: I never remember thinking about an audience.

BLVR: Have there been any gaps in your work life, fallow periods when you didn’t write very much, or very well, books that you’ve abandoned?

DH: Yes, there have been gaps. The first time was a year in my late thirties. Because of a failing marriage. Later, after The Painted Bed, were years of mostly inadequate work… The distresses of old age? Low testosterone? I don’t particularly remember what I did over the four years between The Painted Bed (2002) and White Apples and the Taste of Stone (2006).

BLVR: Is that why you resigned as poet laureate in 2007?

DH: When I arrived in Washington, D.C., as Poet Laureate I had all sorts of ideas of what I might do. I tried a few and failed. Then I felt depressed and never did anything much as a laureate. I did not want to try a second year, because I would only extend my failure. I was withdrawing from something I was not good at.

BLVR: Your best poetry, you’ve said, was written in your forties and fifties. My math puts that at about The Alligator Bride up to The One Day. Was this high period a direct result of the move to Eagle Pond Farm? Or was it having Jane in your life? Or both?

DH: The Alligator Bride has a few poems I like, but really Kicking the Leaves was my breakthrough. I turned fifty in 1978, when it came out—the photograph on the cover is of my Wilmot house, with my grandmother and great-grandfather in the yard. The book began in Ann Arbor and was finished in New Hampshire. It began with my marriage to Jane.

BLVR: What exactly changed with your poems?

DH: It’s hard to say what changed. I revised as much as ever, but the revision was not a movement toward complexity but toward emotional openness and clarity.

BLVR: Is it fair to divide your career into two phases, before and after Kicking the Leaves? Or should it be before and after Jane?

DH: Everything is before and after Jane.

BLVR: You’ve written a lot about Jane’s death, but do you mind telling me how and when you started writing again after she died?

DH: After Jane’s death I spent the first few weeks screaming and visiting her grave. Then one day I began “Weeds and Peonies,” which I did not finish for several years. For five years I spent the early morning writing Jane poems—which became Without and The Painted Bed—never another subject. I was happy writing poems of grief, then miserable for twenty-two hours until writing grief poems again. Working on Jane poems was therapeutic. Your love dies, and what can you do about it? All I could do was express my grief!

BLVR: In Without there’s a trace of something like survivor’s guilt. Did you feel any guilt turning your grief into poems?

DH: I felt more grief than survivor’s guilt, but some guilt. I remember clearly how utterly devoted I was in my attempt to comfort her—and that memory tempered survivor’s guilt.

BLVR: I just read something Paul Bowles wrote after his wife, Jane Auer, died: “What I want is not tranquility, as you put it, and not happiness—merely survival. Life needn’t be pleasurable or amusing; it need only continue playing its program.”

In your work, did you ever feel yourself drifting toward that kind of bleakness?

DH: Bowles was gay. I’m not. After Jane’s death I found myself, willy-nilly, devoted to the pursuit of other women. I was not looking for a wife. Doubtless, coitus interrupted my suffering.

BLVR: You’ve talked about your years in therapy: “Eventually it was psychotherapy that allowed me to recover my life. And to write The One Day.” What changed in therapy that made that work possible?

DH: Psychotherapy began toward the end of my first marriage. I learned that I was mistaken in the names I gave to my feelings. (For love read hate throughout.) Toward the end of therapy I wept because I could not love anyone! Dr. Frohlich told me cheerfully (I had not heard any cheer from him at the start!) that I could love someone. Jane followed.

BLVR: You’ve also written that “Freudian analysis is a word cure, and it resembles the way we read or write poems.” Can you explain? Is there symmetry between poetry and psychoanalysis?

DH: I can’t or won’t answer!

IV. “MY SPIRITUALITY HAS GONE DRY.”

BLVR: You received the 2010 National Medal of Arts. I have on my refrigerator a newspaper photograph of you and President Obama during the ceremony at the White House. It looks like the two of you are old friends sharing a raunchy joke, and I was surprised to read in Essays after Eighty that you couldn’t actually hear what he said. Can I ask what your impression of Obama is, as either a president or a person, or both?

DH: Yes, President Obama talked into my deaf ear, and I was too excited to tell him! When John Ashbery, in an interview, quoted Obama as talking to him about contemporary American poetry, it seemed to me that I heard what Obama had said. I have always liked Obama, and of course voted for him twice. Someone once showed me a letter he wrote before he was married, maybe when he was at law school, talking about Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” He was comfortable talking about it, writing to a girlfriend. I suppose he was trying to get into her pants. Probably he kept up with poetry to a degree, and never felt alien to it.

BLVR: In your poetry there’s a theme of continuity, a constant reaching back through the years. I can flip through The Selected Poems and find it in “The Stump,” “Flies,” “Ox-Cart Man,” to name a few. Even Jane’s death in a way is another link in the chain from the past to the present—Jane died in a back bedroom at Eagle Pond Farm, in the very same bed in which you plan to die. Is this continuity a source of consolation for you?

DH: Maybe I live for the continuity? Yes, I hope I’ll die in the same bed. I do love the continuity of house and landscape—and the continuity of writing my whole life. After I die, my grand-daughter, Allison, will move into the house. One family has lived here continuously from 1865 to… Maybe Allison will be followed by her grandchild? I followed my ninety-seven-year-old grandmother, the youngest child of my great-grandfather.

BLVR: I wanted to ask about your beard and whether it falls on any kind of multigenerational continuum? Is it, in other words, another link to the past? I find a lot of beards in your poems, for instance Freeman’s in “Daylillies on the Hill, 1975–1989,” which is “wagging around his permanent smile as he talked without stopping.”

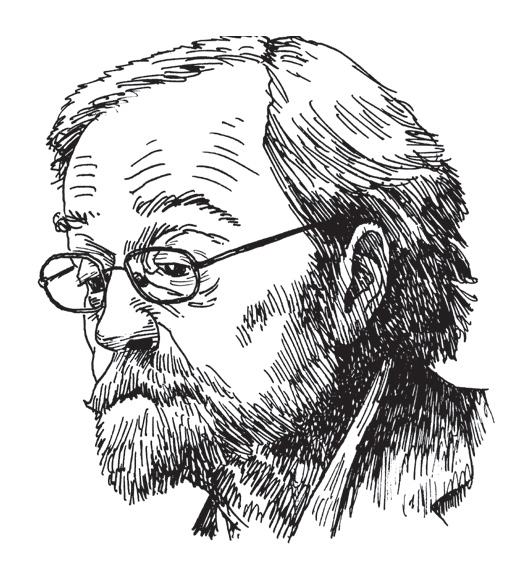

DH: In Essays after Eighty I wrote an essay called “Three Beards.” I don’t think that my first beard derived from Freeman or anyone in my family. It was a way to distance myself from other assistant professors of English. My last beard has altered so much over the years. When I first grew it, not long after Jane died, it was tiny and kempt. Eventually it vastly erupted, scraggly and uncontrolled—or controlled to be wild. At the same time I stopped combing my hair, or arranging it at all. I became the face on the cover of Essays after Eighty. I loved looking like a madman for my late poetry readings. It did not limit my hairiness when I rubbed testosterone on my chest.

BLVR: I read that you’re a deacon in your church. Do you consider yourself to be a Christian, or is your work guided in any measure by Christian theology?

DH: Jane was a deaconess and I was a deacon. I followed Jane in her spiritual life, as I followed her in so many things—the follower nineteen years older than the leader. After Jane died, I continued church for many years. Now my legs are bad and I have stopped climbing those stairs. But also my spirituality has gone dry. I no longer have Jane to follow. Jane’s best-known poem is “Let Evening Come.” I cannot read the line: “God does not leave us / comfortless…” The day we knew she was going to die, Jane said that she did not fear punishment. But she did not say anything about paradise.

BLVR: You’re a baseball fan. You even tried out for second base with the Pittsburgh Pirates at a time when you weighed around two hundred and fifty-pounds. “I was cut for not being able to bend over, which wasn’t fair,” you said. What happened?

DH: My agent had a friend in the Pirates management and he gathered several of his writers to try out together. There were five or six of us, but I was the only one who did everything. We made a book out of our endeavors, Playing Around, which did not sell much. My essay first came out in Playboy and then was part of my sports-essay collection, Fathers Playing Catch with Sons. It was during this try out that I met the pitcher Dock Ellis. A year later, I did a poetry reading in Florida at the time of spring training, visited my old teammates, and Dock and I for the first time talked about doing a book together.

BLVR: You’ve called baseball “the preferred sport of American poets.” What draws you—and American poets—to the sport?

DH: Back in the 1980s a magazine asked me to write a piece about why American poets like baseball. I made something up and they published it. Almost immediately another editor asked me to write a piece on the same subject. So I made up another reason. A third time I made up a third reason. When the fourth editor asked me, I couldn’t think of yet another reason.

V. REJECTING FRANK O’HARA

BLVR: You played softball with Robert Frost. What did meeting him mean to you as an aspiring poet?

DH: Even in his sixties, Frost could swing a bat. Certainly it thrilled me to meet him. We even sat and talked together. Decades later, he told a crowd that he had raised me from a pup. He hadn’t, really, but meeting him when I was so young afforded me a sense of endurance.

BLVR: What other poets were your guiding lights early on?

DH: By age fourteen, I was asking for poetry books for my birthday. Eliot was the first one. I tried everybody—Cummings, Fearing—and got to Hart Crane fairly early. Yeats. Hardy…

BLVR: When you interviewed Ezra Pound for The Paris Review in 1962 he had, in your words, “not yet entered the silence, but the silence was beginning to enter him.” Did he have any notion of how far he’d fallen, not just in public esteem but in his own mind? Or was he oblivious?

DH: Pound knew that he had fallen in both public and literary esteem. In the interview he wanted to reestablish himself. As we talked, he kept feeling that he was failing. After the interview, he collapsed into a final and lengthy silence.

BLVR: A question you put to Pound fifty years ago: what’s the greatest quality a poet can have?

DH: I believe Pound said “curiosity.” I would be more apt to speak of diphthongs and mouth pleasure.

BLVR: Who do you think are the best English language poets working today?

DH: There are three young poets I particularly follow—in their mid-fifties—but I would rather not name them. I still believe that Geoffrey Hill is the best poet writing in English today.

BLVR: You were at Harvard with Kenneth Koch, John Ashbery, Robert Bly, and Frank O’Hara, who accused you of writing second-rate Yeats. Adrienne Rich was at Radcliffe. That’s a heady mix of poets. How much, if at all, did you influence one another’s work? Was it a friendly rivalry, or was there a knife waiting around every corner?

DH: There were no knives. Frank O’Hara and I used to sit in a booth at Cronin’s drinking beer and talking poetry. Earlier, the first class I attended at Harvard included Frank, with his terrifying wit. Was this what Harvard would be like? Frank and Edward Gorey (his roommate) gave the best parties at Harvard. Years later I rejected some of Frank’s poems when I edited for The Paris Review. Stupidly, although these poems were from the “Second Avenue” moment, not the best Frank. His sarcastic letter in response to rejection was classic. He was a genius.

BLVR: Has American poetry changed for the better or worse in your lifetime?

DH: The face of American poetry has utterly changed. In 1948, there were eight poets in the United States. In 2018, there will be 7 million. This is not entirely a good thing. At first, I was hysterical about the explosion of numbers, and once said about the creative writing industry, “I loathe the trivialization of poetry that happens in creative writing classes.” Such hysteria is useless. In any year, in any century—1932, 1882—almost all published poetry is terrible. It is true when there are only a few poets. It is true when there are millions.

BLVR: I get the feeling that, at least outside literary circles, “poet” is almost a slur. Poets are people who wear tweed and smoke French cigarettes and speak in rhyme and meter, or the language of poetry is ornate, difficult, too removed from real, lived experience to be of any use. Why, after three hundred years of American poetry, it is still a remote planet inhabited by an alien race?

DH: Of course you are correct about the general attitude toward poetry—at least since the seventeenth century. (There was limited literacy back then!) There is a general notion that poetry is for other, weird people. Part of the problem is the way that it’s taught in schools. I think poetry should be taught backward chronologically, with students starting with contemporary poets and working back to the poets of the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.

BLVR: I wanted to ask how you feel about your work’s longevity. I’m thinking of a line in Essays after Eighty: “I expect my immortality to expire six minutes after my funeral.” After an eighty-year career, does the prospect of your work being forgotten depress you, or does it come with the territory?

DH: I’ve lived long enough, among generations and generations of poets. I have seen so many highly praised people disappear quickly after they die. I don’t see why I should be an exception.