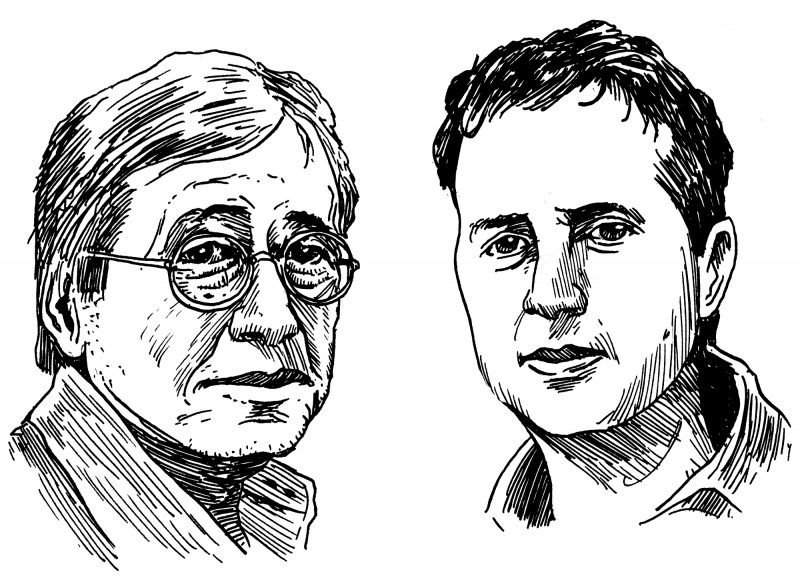

“Barry Hannah is America’s greatest living writer” is something I started saying when I first read Hannah’s work in the late 1990s. I’m sad I had to stop saying it on March 1 of this year, when Barry passed away.

In July 2008, Barry invited me down to Oxford, Mississippi, where he lived. I spent three days in Oxford, riding around, chatting with the tape recorder, rolling and smoking cigarettes, a habit I picked up for the weekend. It wasn’t a convenient time for Barry to entertain a guest. His wife, Susan, was going through chemotherapy, and Barry’s health wasn’t too good, either. He ran out of breath a lot. His oxygen tank kept clanging around in the back of his Jeep. Still, he was a gracious and ambitious tour guide. He showed me Faulkner’s home, and took me to Square Books, Oxford’s venerable bookshop, and one afternoon he took me out to the catfish pond of the late writer Larry Brown. Larry’s gravestone sits near the shore of that pond. While we were there, Barry started talking to the stone, telling Larry how much he missed and admired him, an affirmation of love between friends that puts a rock in my throat when I think about it still.

Barry’s work drove people to fanaticism. I know a writer who memorized the first five pages of Hannah’s novel Ray, and someone else who claims he’s bought two hundred copies of Airships just to hand out to people who haven’t read it. Yet it bothered Barry that he didn’t have a broader audience, that he had only one “airport book” with his last novel, Yonder Stands Your Orphan. Why he didn’t have more airport books is a mystery to me. Even though Hannah populated his novels and stories with serial killers and devils and a guy who kills his lover with a razor strapped to his loins, I’d argue that any one of Hannah’s sentences picked at random holds more hope and joy than the entire self-help section at the O’Hare Barnes and Noble. Hannah loved Flaubert as a fellow member of the mot-juste tribe, though Hannah wasn’t satisfied with just the right word, it had to be the fiery, ecstatic word, too, a Molotov cocktail against syntactic dreariness.

—Wells Tower

I. PRETENDERS V. SONS OF BITCHES

[It’s a weekend afternoon in Oxford, Mississippi, July 2008. Barry Hannah asked me if I’d ever been to Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s estate. I never had. Barry seemed to think it was important that we go have a look around. We’re driving over in Barry’s Jeep.]

WELLS TOWER: Do you still read much Faulkner?

BARRY HANNAH: Yeah,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in