The Apologetic Preface

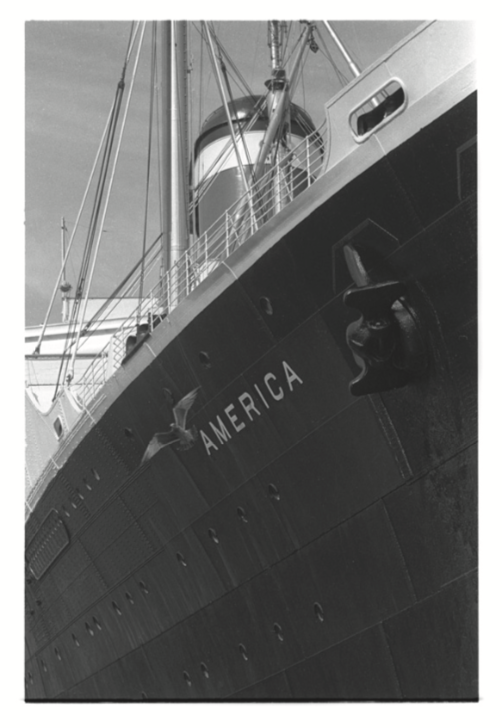

This text was initially written as a lecture, delivered on May 1, 2008, to the translation program at Princeton University. At that time, my essay on novels and translation, The Delighted States, had not yet been published—by Farrar, Straus and Giroux—in America. (It was published in June.) Shamelessly, therefore, I self-plagiarized, to a mildly lavish extent. I also rewrote what I had plagiarized, and sometimes contradicted it. The rare reader who has literally just read The Delighted States must therefore content themselves with the exasperated pleasure of grumbling.

The Essay that was once a Lecture

I.

In 1947 Theodor Adorno, a German and Jewish émigré living in Los Angeles, published a book called Philosophy of Modern Music. The philosophy of this book could be reduced to a simple thesis. Adorno didn’t like the music of Igor Stravinsky—a Russian émigré, also living in Los Angeles. He did like the music of his friend Arnold Schoenberg, a Jewish-Austrian refugee. Who also lived in Los Angeles, and was Adorno’s neighbor.

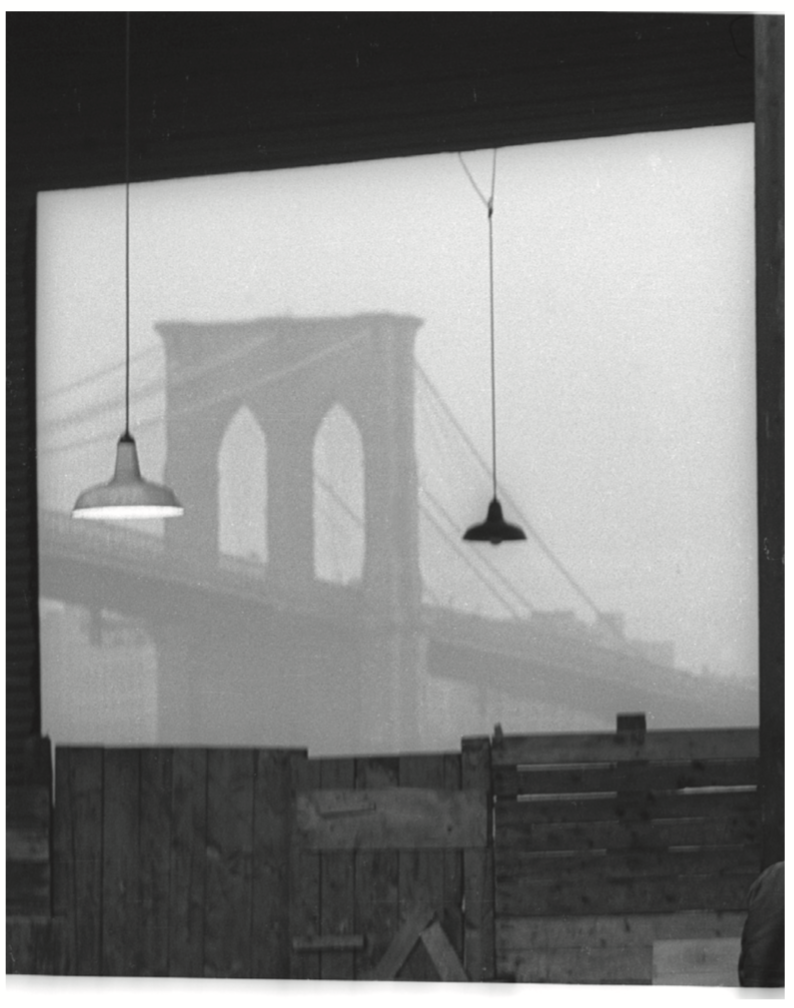

This story about America—which is, therefore, a story about European exile—can function as a kind of allegory: an overture.

In his book, Adorno wanted to define what gave a musical work a value. This was a test case for what gave any aesthetic object a value. Adorno loved the music of Schoenberg because, he argued, it was both entirely new and entirely authentic. This was why it represented a value in the history of music. Whereas Stravinsky, whose art explicitly reworked the history of music, was a historical irrelevance. He lacked heart. In a century riven by terror, the only solution was music as original and dissonant as Schoenberg’s. “What radical music perceives,” wrote Adorno, “is the untransfigured suffering of man.” Stravinsky, argued Adorno, was only flippant. He was too concerned with the history of his art to be aware of the history of his century. He only wrote “music about music”—having “succumbed to the temptation of imagining that the responsible essence of music could be restored through stylistic procedures.” According to Adorno, Schoenberg was great not because of the quality of his technique but because of the quality of his despair. His art was more authentic.

A year after Adorno published his Philosophy of Modern Music, Schoenberg’s oratorio A Survivor from Warsaw received its first performance—in America, by the Albuquerque Civic Symphony Orchestra. The initial rendition left the audience speechless. When the conductor...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in