Take good care, Gambetti, not to visit the places associated with writers, poets and philosophers, because if you do you won’t understand them at all.

—Thomas Bernhard, Extinction

*

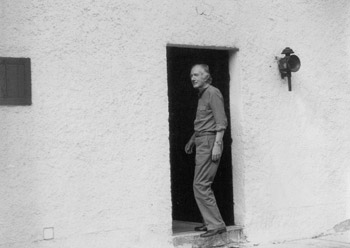

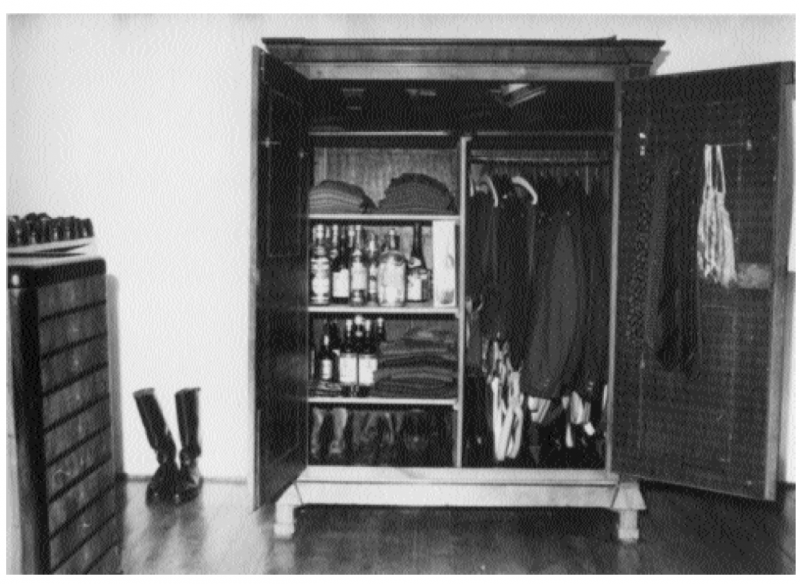

I had planned our excursion to Das Bernhard-Haus, the Thomas Bernhard house, near the village of Ohlsdorf in Upper Austria, with embarrassment. It was just the kind of admiration behavior, I thought, that Bernhard himself would have found shameless: traipsing from room to room around an author’s house that has been turned into a kitschy museum, looking at the author’s possessions inside the author’s house; worst of all, to perhaps stare at the author’s typewriter on the author’s desk. One would hope to be above supposing that it was anything but spying, to seek to learn anything about a writer by gawking at his kitchen or bedroom.

The greatness of Bernhard’s novels and memoirs is, after all, philosophical, and stylistic. A brutally simple and apparently universal idea—Everything is ridiculous when one thinks of death, he said upon receiving Austria’s Förderungspreis für Literature in 1968—is embroidered into a vivacious comedy of pure thought, through compulsive repetition, confident self-contradiction, and heady exaggeration. It is, I thought, art to be contended with on its own terms—in the echo chamber of the solitary mind, not on the guided tour.

*

Real intellect does not know admiration.… People enter every church and every museum as though with a rucksack full of admiration, and for that reason they always have that revolting stooping way of walking which they all have in churches and museums, he said. I have never yet seen a person enter a church or a museum entirely normally, and the most distasteful thing is to watch those people in Knossos or in Agrigento, when they have arrived at the destination of their admiration journey, because the journeys these people take are nothing but admiration journeys.

—Old Masters

*

But while contemplating a trip to Austria last summer, I learned that Bernhard’s 1963 debut novel, Frost, was soon to appear in English for the first time. I pulled down the books that sat together on my shelf, years after I had figured, with some sadness, that I had read all the Bernhard prose there was to read, at least without rectifying my inability to read German.

I recalled their archetypal settings: decrepit ancestral estates amid unfathomable forests; river gorges that roar unrelentingly; valley hamlets populated by the crippled human products of the stultifying Austrian state. On the map all around...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in