It is clear that if there is to be any revival of the utopian imagination in the near future, it cannot return to the old-style spatial utopias. New utopias would have to derive their form from the shifting and dissolving movement of society that is gradually replacing the fixed locations of life.

—Northrop Frye, “Varieties of Literary Utopias”

Nowadays we do not resist and overcome the great stream of things, but rather float upon it. We build now not citadels, but ships of state.

—H.G. Wells, A Modern Utopia

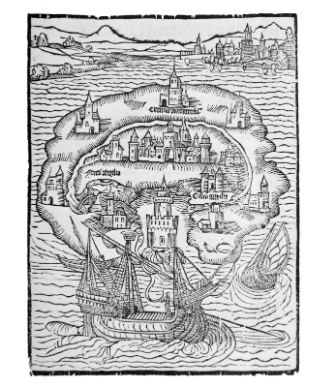

At the start of William Alexander Taylor’s 1901 utopian novel, Intermere, a small steamship runs into a fog bank three days north of the equator and drifts into a whirlpool. “I felt myself being dragged down to the immeasurable watery depths,” the hero recounts. He loses consciousness, and promptly wakes in a hammock on the curved deck of an entirely different kind of vessel—one with a “succession of suites and apartments, richly but artistically furnished.” The hero imagines for a moment that he is already in paradise, but the ship, a “merocar” propelled by “supernatural agencies,” turns out to be one of many technological advances engineered by a perfect society hidden inside the earth.

The jump from steam-powered transport to luxury yacht places Intermere midway along an evolution in utopian thought: A range of authors, architects, and engineers first identified paradise as a floating island, then as an island accessible by ship, and finally as the ship itself. Transport became destination.

In 2002, when the forty-three-thousand-gross-ton vessel the World shoved off from an Oslo wharf—christened by a triumvirate of Norwegian priests with a cocktail of holy water and champagne—it marked the first time it was possible to own real estate on board a ship.

The launch was greeted with telling fanfares.

“A global village at sea,” said the Boston Globe.

“Utopia afloat,” said Macleans.

*

I flew to Norway to meet the man who had coaxed utopian ships off the drawing board. Knut Kloster Jr. met me at the airport wearing a sea captain’s cap low on his brow so I could recognize him. It was odd to be met by Kloster himself. He was the father of the modern cruise industry, and the visionary scion of one of Norway’s oldest shipping families.

“I’m glad I don’t have to wear this hat anymore,” Kloster said.

On the drive into Oslo, he felt obliged to point out the city’s new high-speed train, and for the next couple of days he would sustain that act of reluctant tour guide. Kloster was almost eighty, but he was...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in