Jerry Moriarty is one of the great geniuses of the comic strip. If you’ve never heard of him, don’t blame yourself; he’s been out of print for almost three decades. Fortunately, however, a new collection of his work, The Complete Jack Survives, has just been published by Buenaventura Press, and it beautifully reprints, reconfigures, and revives the groundbreaking work that first appeared in and was later assembled by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s RAW Books imprint in the early 1980s. Bold, unassuming drawings blur the imagined essences of Moriarty and his father into unpretentious, searching comic strip compositions that stick in the memory like melodies; it’s as if Edward Hopper had taken up songwriting, or Ernie Bushmiller had taken up painting, or Edvard Munch had actually loved his father. For lack of a better word, it’s poetry—I believe the first that comics has ever seen—and poetry as fresh and affecting now as when first drawn.

One of the few painters to stick with unironic representation when it seemed least fashionable to do so, Moriarty tackled the direct narrative potential of picture-making with the domestic frankness of a short-story writer, creating characters and situations that act out semiautobiographical resuscitations of family, loss, and adolescence. His related masterful and game-changing comic-strip experiments in the 1970s and ’80s influenced a generation of cartoonists for their quiet solidity, introducing solemnity and eternity in a medium that normally trades in the snappy and the lurid. In short, Moriarty has prepared a body of mostly unseen work that is unmatched, in my opinion, for its accessibility and humanity in the accepted history of painting and visual narrative. As clear and loud as a distilled recollection, Jerry’s art vibrates with a balanced uncertainty that feels as fleeting as life itself; one is left with the sensation of having seen into the mind of the artist himself and, by turn, one’s own memories, which every day grow more rounded and distant.

Born in Binghamton, New York, in 1938, Moriarty graduated from the Pratt Institute in 1960 and has taught at the School of Visual Arts in New York since the early ’60s, yet he has had only a handful of shows. He does not sell his paintings or drawings and lives a life of controlled austerity, expecting little other than to paint and draw. In addition to Jack Survives, he’s long been at work on a lengthy collaboration between his paintings and cartoons, Sally’s Surprise, which may see print as early as next year.

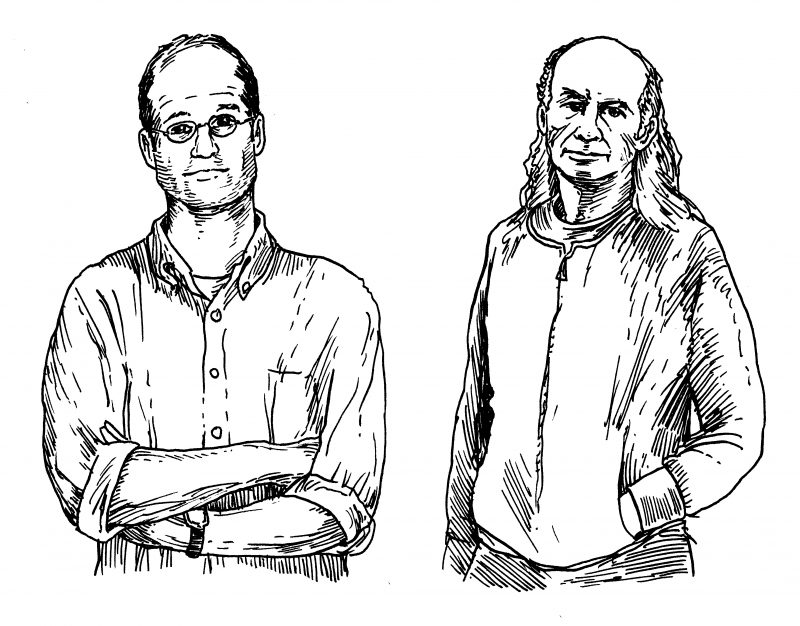

It’s no surprise that Moriarty is as thoughtful and unaffected as his work; by contrast, the reader will please forgive the interviewer’s fussy, pedantic questions. This interview was...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in