Mayakovsky was better known as a person, as an action, as an event.1

Even at this distance—more than seventy-five years after his death and nearly twenty years after the collapse of the government he fervently promoted—it remains difficult to account for the phenomenal nature, the sheer outlandishness, of Vladimir Mayakovsky. As unofficial poet laureate of the Russian Revolution—“my revolution,” he called it—Mayakovsky had unrivaled authority and glamour, taking on multiple responsibilities and roles—orator, playwright, magazine editor, stage and film actor, poster maker, jingle writer—with a singular mix of self-mockery and martyrdom.

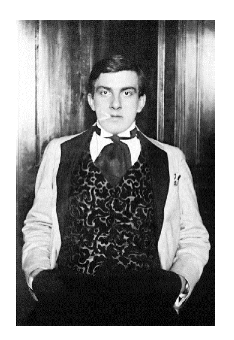

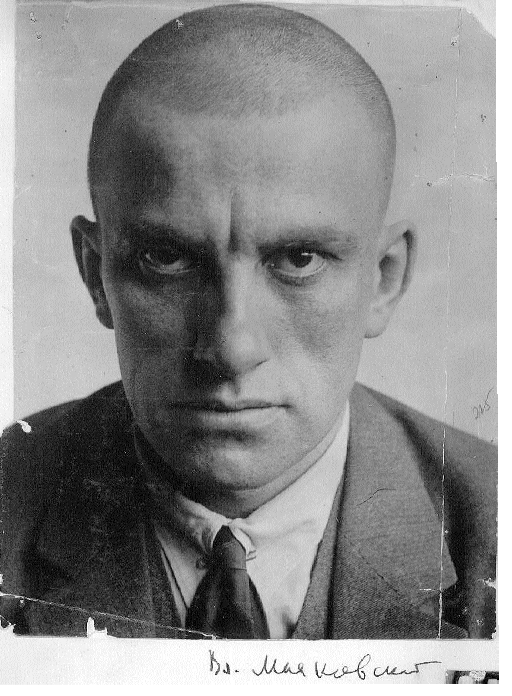

Photographs of the poet—particularly the glowering, shaved-head portraits taken by Aleksandr Rodchenko in 1924, when Mayakovsky was thirty-one—display a kind of proto-punk ferocity, a still-burning aura of tough-guy tenderness, soulful defiance. The poems are virtually inseparable from this persona, as Mayakovsky made theatrical appearances in his verse and made a spectacle of his personal life. “He felt the need,” his friend Viktor Shklovsky wrote, “to transform life.” And so it followed that for Mayakovsky, poetry itself was transformative. He channeled experiences directly into his work while being convinced that the resulting poems could pace and project the ideals of a new social order.

*

He was calm, massive, and he stood with his feet slightly apart, in good quality shoes that had metal reinforcements and tips.

It may be bewildering, now, to imagine a poet expecting his words to translate into an active force for change, but this conviction was at the center of Mayakovsky’s life and work, and it was shared by a generation of artists coming of age in the revolution’s early, ecstatic wake. (Auden’s famous circumspect assertion that “poetry makes nothing happen” would have been greeted by Mayakovsky with a howl of derision. Rodchenko and his typographical counterpart, El Lissitzky, would have whipped up terrific corroborating posters.)

Mayakovsky was born in Bagdadi, Georgia, in southern Russia, on July 7, 1893. His father, a forest ranger, died from blood poisoning when Vladimir was twelve, and the remaining family—Mayakovsky’s mother and two older sisters—moved to Moscow, where Vladimir went to high school. He had an early start in anti-czarist sentiment: incited by a pamphlet brought home by his sister, he participated in a pro-Bolshevik demonstration the year before his father’s death, became an active party member at age fourteen, and was arrested twice before being jailed for aiding the escape of a political prisoner from Novinsky Prison. He was locked up for seven months, and served much of the sentence in solitary confinement. His first arrest, the previous year, followed from his involvement with an underground printing press—solidifying the link in Mayakovsky’s mind, you might guess, between printed...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in