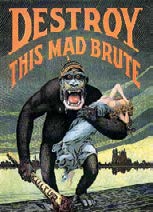

Destroy This Mad Brute: The African Roots of World War I

The hundredth anniversary of the start of the First World War, currently being observed pretty much everywhere, has poured forth a whole variety of stark and sobering images, but the one that really startled me the other day was that of a US Army enlistment poster from 1917, fashioned by the noted stage designer H. R. Hopps and in turn based, we are told, on a whole slew of British propaganda images from earlier in the war: a huge, hulking, drooling man-ape, capped by a pointed Kaiser-helmet (labeled MILITARISM), with one arm wielding a mammoth club (labeled KULTUR) and the other gripping a half-naked, fainting maiden, lumbering out of the sea onto dry land (labeled AMERICA). The abject ruins of his European depredations smolder in the far distance behind him: “DESTROY THIS MAD BRUTE” implores the none-too-subtle poster’s none-too-subtle headline. And we are off: welcome to the rest of the century.

It was the sheer incongruity of the Germany-as-African-gorilla motif that first got to me, but as the weeks passed, the twisted visual rhyme came to seem somewhat more apt: I’ve been thinking a lot about the African roots of the First World War, or rather the ways in which Europe’s ever more grotesque and monstrous depredations across that continent, especially toward the end of the nineteenth century, set the tone for everything that was to follow back in Europe during the next. World War I can be seen in this light as an instance of karmic blowback, with Europeans simply starting to do to each other what they had already been doing to Africans for some time—which is to say, starting to see each other in the same kinds of barbarian, subhuman terms they’d once lavished upon their colonial subjects (the sort of terms that had in turn allowed them to innovate in Africa the barbed-wire trench warfare, mass machine-gun embankments, concentration camps, and the like that now made their way back to the home continent). In this regard, things weren’t altogether unlike what had happened earlier, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, especially during the unbelievably gruesome Thirty Years’ War, when Europeans simply took to launching the kinds of religious crusades against each other that they had earlier foisted upon the Muslim Arabs of the Middle East.

For that matter, much of the moldering cultural and even scientific ferment that characterized the first decade and a half of the twentieth century, and that laid the foundations for much of what we consider “modern” today, can be traced back to the ways in which Europe was already wrestling with its bad-faith...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in