In 1869, Antonie Zimmermann became the first translator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and Germans were treated to Lewis Carroll’s classic in their native tongue. Sort of. As you might imagine, Alice’s Abenteuer im Wunderland took some pretty serious liberties with the original. How else could Zimmermann have dealt with the Mock Turtle, who studies “reeling and writhing”? Or Alice’s rendition of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Bat (how I wonder where you’re at)?” Or the Mouse’s Tale?

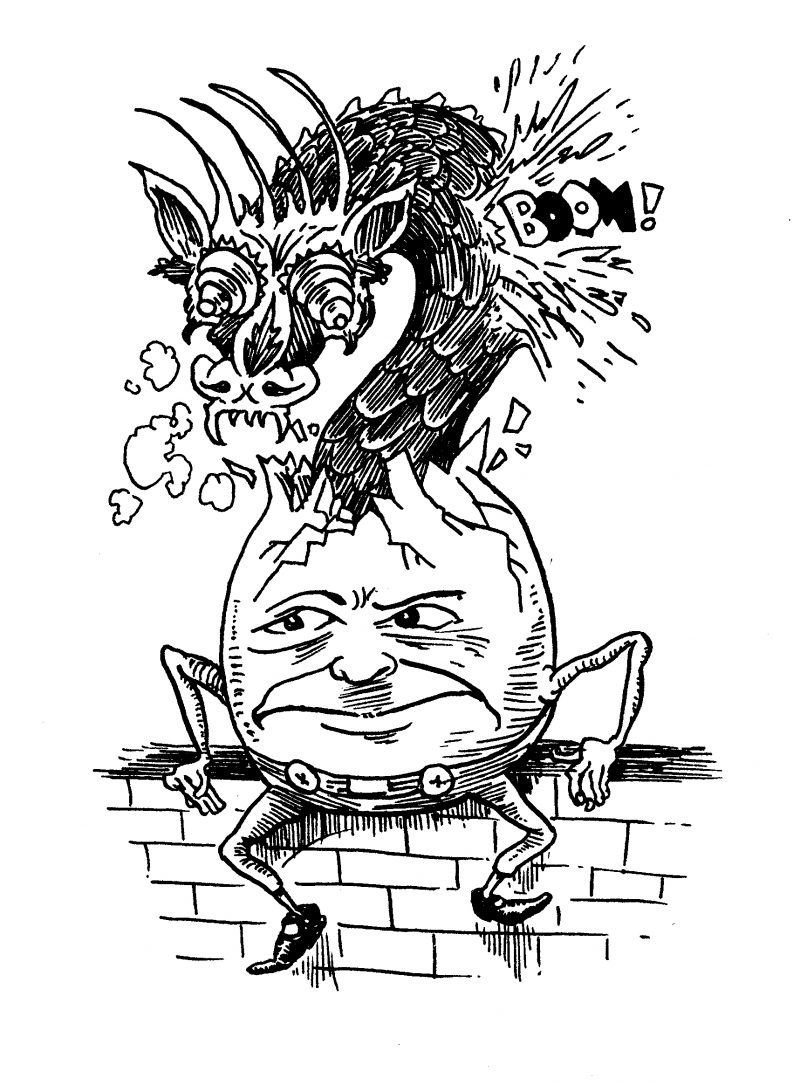

But these problems were child’s play compared to the nightmare facing Helene Scheu-Riesz, who in 1923 produced the first German translation of Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There. Aside from constant puns and indecently long, colloquial poems, Carroll’s sequel added an unprecedented challenge in the form of “Jabberwocky,” seven stanzas of nonsense verse packed with twenty-five invented words.

Scheu-Riesz bungles her effort, starting with the poem’s title, which she abbreviates to “Jabberwock” for no apparent reason. The last stanza, a repeat of the first, is inexplicably left out. While frumiousen Banderschlangen works well for frumious Bandersnatch (schlangen means “snake”), Jubjubvogel and Tumtumbaum are lackluster transliterations of Jubjub bird and Tumtum tree. That said, those who value strict textual fidelity might prefer her version to more-adventurous ones that followed, like Jaime de Ojeda’s “Galimatazo,” in which the young hero is cautioned to beware el pájaro Jubo-Jubo and shun el frumioso Zamarrajo, before he rests under el árbol del Tántamo.

Textual fidelity is always an issue for translators, and never more so than in the case of nonsense. Take one simple line: “He chortled in his joy.” To a modern reader, chortle is not nonsensical. It’s right there in the dictionary between chorology and chorus. Yet at the time of “Jabberwocky”’s publication, chortle made as much sense as slithy and brillig, words that, like chortle, were also Carroll’s own invention (and, unlike chortle, incur the wrath of Microsoft Word’s squiggly red line).

Should translators render chortle as a nonsense word in their target language? Modern English readers wouldn’t take it that way, so why should modern French readers, say, be forced to experience something different? But if the translator’s goal is to re-create the reading experience of Carroll’s Victorian audience, or at least honor Carroll’s original intentions, then faithful translation ought to yield a new nonsense word. Of course, adopting that goal means responsible editors of modern English editions should replace chortle with snortle, or...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in