Scroll

Scroll

Time Well Spent

December 1st, 2021 | Issue one hundred thirty-eight

It’s often said that we live in an attention economy. Various media and technology corporations—whether it’s Instagram, HBO, Spotify, or Twitter—are in constant competition for our attention, and not only against other media; the CEO of Netflix once said that its primary rival was sleep. But these companies are not the first to stake a claim on our attention—artists have long known how to solicit, capture, and repel the attention of their audiences. Attention is how we process things that are new and surprising, or intriguing and difficult—a fact artists must be aware of. Our attention might be compelled by a catchy pop-music melody or a delightfully colorful painting, but it’s also what we summon to persevere through a piece of dissonant experimental music or a lengthy film. We often give our attention to what pleases us, but we don’t give it only to easy sources of pleasure: we give it in order to understand, to ask questions, to wonder.

The phrase attention economy poses attention as a commodity to be portioned off and sold, usually on the internet. (We also say that attention is something to be “paid.”) But maybe attention is more a state of mind, akin to happiness or disgust, than a currency. It’s a feeling, a state of alertness that we can choose to enter, forestalling judgment for the sake of gathering information. The best artists coax us into this state, then manipulate that focus. John Cage, whose compositions strain our attention—like his famously silent “4’33″”—was well aware that sustained concentration over time can change and deepen perception. “If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, try it for eight, sixteen, thirty-two, and so on,” he wrote. “Eventually one discovers that it’s not boring at all but very interesting.”

Now, spending just thirty-two minutes looking at a single screen would be considered an accomplishment. We scroll on our phones while watching Netflix, or watch Netflix while scrolling on our phones. When I find myself falling into this toggling routine, I try to remember that technology can also push us toward other forms of durational attention. Artists like Cage, Nam June Paik, and Christian Marclay pioneered these forms, provoking ambivalence rather than addiction in their audiences. The nine works below explore some of the possibilities for new forms of engagement. Each uses our attention in a different way, demanding a lot or a little of it, but always deliberately.

Table of Contents

- 1. Erik Satie, “Vexations” (c. 1890s)

- 2. Andy Warhol, Empire (1964)

- 3. Nam June Paik, TV Buddha (1974)

- 4. Penn and Teller, Desert Bus (1995)

- 5. Nintendo, Pocket Pikachu (1998)

- 6. Christian Marclay, The Clock (2010)

- 7. The TikTok feed (2016)

- 8. ChilledCow, “lofi hip hop radio—beats to relax/study to” (2017)

- 9. Laurel Schwulst and Soft Works, Flight Simulator (2019)

Erik Satie

c. 1890s

“Vexations”

Satie pioneered ambient music, but he called it “furniture music”: compositions that decorate a room like pleasant wallpaper, short loops that evoke a mood but stay consistent. You weren’t supposed to pay attention to it; when guests of the theater where he debuted his furniture music filed to their seats, Satie yelled at them to stop. “Vexations,” however, took the idea of staying in the background to an entirely different level. The piece, a scrap of composition discovered after Satie’s death, has a discordant, plodding melody. Its inscription reads: “In order to play the theme 840 times in succession, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand, and in the deepest silence, by serious immobilities.” Contemporary musicians have taken this as a commandment to indeed play “Vexations” 840 times in a row, a task that took eighteen hours the first time it was staged, by John Cage, in 1963. I once attended a staging at the Guggenheim in New York City; piano players rotated every fifteen minutes or so to break up the tedium for both players and listeners. The music seemed to deny attention: anytime you focused on it, the melody would slip away.

ANDY WARHOL

1964

Empire

Warhol broke cinema, or at least the expectation that films should be entertaining. Empire is an eight-hour-long single shot of the Empire State Building. Warhol said his goal for the work was “to see time go by,” and indeed the black-and-white film captures time in all its implacability. There is nothing interesting about the image on-screen apart from the architecture, and the eye absorbs that after just a few minutes. What’s left is the slowly shifting night sky and perhaps a dawning awareness of perception itself: the viewer pays attention to their own act of seeing, mirrored by the camera trained on the building. At the film’s ticketed debut, a crowd gathered around Warhol to demand their money back. They’d witnessed history, and had found it boring.

Nam June Paik

1974

TV Buddha

This single sculpture from 1974 foretold our modern relationship with screens. A Buddha sits on a bare white plinth, facing a television set placed at the other end. A camera behind the television points at the Buddha, transmitting its image onto the TV’s bubble-like screen. The Buddha, then, stares at a broadcast of himself, caught in an endless, mediated loop of self and reflection. Is the Buddha sculpture real, or is the image real? Are they both real? Perhaps reality exists somewhere in between, in the camera lens receiving the light and the electrons translating the picture onto the screen.

Paik’s Buddha meditates on this question, immersed in its contradictions. We watch screens to see ourselves reflected and refracted, amid the sea of social media and streaming television. That experience is often alienating—unlike the state of transcendence that TV Buddha evokes. Paik once said that his goal as an artist was “to look for the new, imaginative and humanistic ways of using our technology.” We see this in the playfulness of the sculpture—itself a Zen koan—and in his enduring love for analog materials, chunky televisions, and screens stacked atop one another. It’s a sense of play that’s utterly missing from the slick landscape of contemporary media.

Penn and Teller

1995

Desert Bus

Desert Bus is a video game created by the magicians Penn and Teller. It was never released, and it’s easy to understand why. The game is an exercise in real-time attention; playing it is a quasi-meditative act that translates physical labor into digital motion. The player’s task is to drive a truck for an eight-hour shift, from Tucson to Las Vegas and back again. The in-game truck has a slight tire misalignment, so players must continually correct the steering wheel lest they run off the road and be towed back to the start. If your focus wavers once, it’s all over—a challenge both physical and spiritual. “I’ve achieved a Zen-like state while playing it, where it doesn’t bother me as long as I don’t think about it,” one player told The New Yorker. Fun is not the point; unlike most apps, the game does nothing to appease the player. Perhaps that’s why some players now use it as an endurance test to raise money for charities, similar to running a marathon.

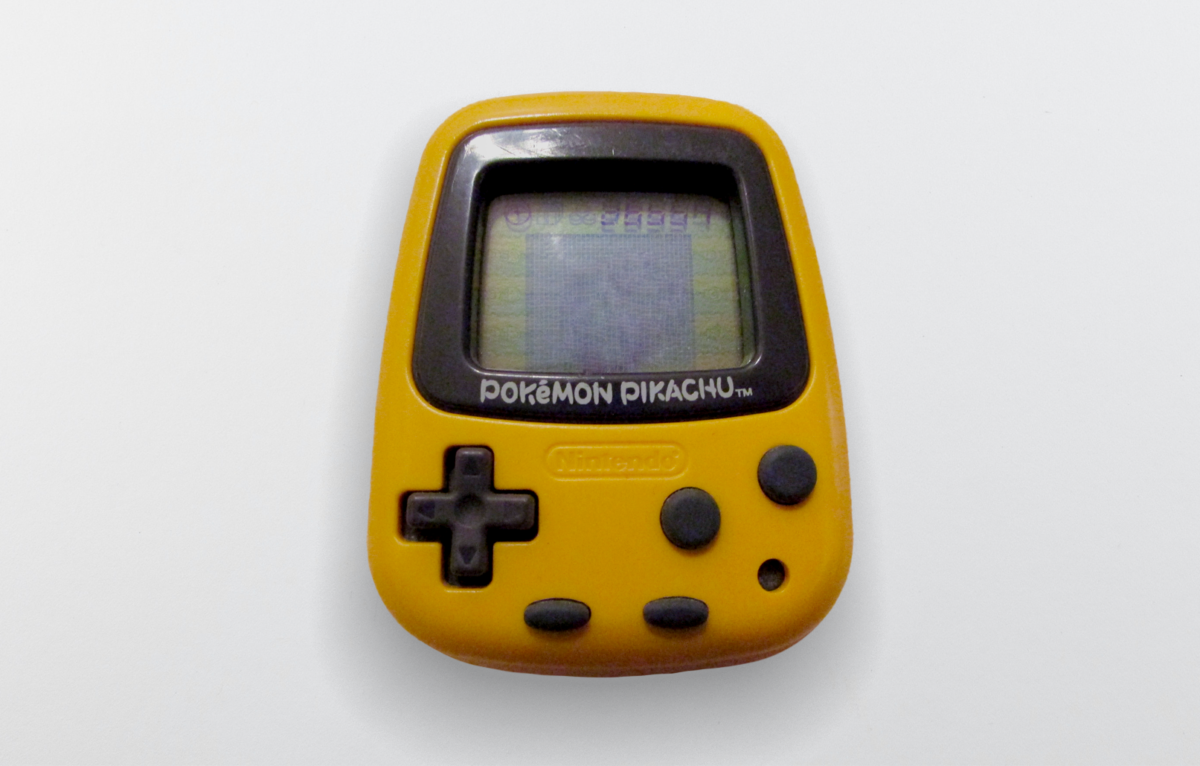

Nintendo

1998

Pocket Pikachu

This gadget was the first piece of technology I became addicted to. I was in elementary school, and the ovoid yellow plastic casing fit snugly in my pocket like an iPhone; I took it out and checked the LCD screen a dozen times a day, the way I now open Twitter. Nintendo’s product was essentially a knockoff of Tamagotchis, electronic pets that you had to care for by feeding and cleaning their poop multiple times a day, lest they die. But instead of shapeless blobs, the Pocket Pikachu contained the famous electrical Pokémon, whose familiarity inspired in me a deeper loyalty. I had to keep Pikachu alive!

The Pocket Pikachu had reward mechanisms that anticipated the dopamine rush of the Facebook like. As my Pikachu got older and grew in size, I gifted it watts that I won by playing an in-game slot-machine. The device couldn’t be turned off; it was on as long as its battery lasted, preparing me to allot it the same ambient attention I now pay to the internet, a space I can never seem to fully escape. Like we once did the Pocket Pikachu, we carry its distractions with us.

Christian Marclay

2010

The Clock

“Durational artwork” or “time-based media” are two wonky art-world phrases used to describe works that unfold in front of the viewer and change over time. They can refer to video art, to video games, or to experiences that play out in a web browser. What is time, anyway, when we chop it up into infinitesimal pieces, when we fragment our attention between a hundred different sources of content? The fragments must be reassembled in some way, given a new context and meaning. Restitching our multimedia landscape is another role that art can play.

Marclay’s The Clock, one of the landmark works of the twenty-first century, is composed of a montage of movie clips that refer to marking the time of day—second hands tick by, people check their wristwatches, church bells ring. The clips are strung together into a cinematic replica of twenty-four hours that is exactly twenty-four hours long. It’s a hypnotic fiction of real time; hours passed as I watched the piece at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, drawn in suspense from one clip to the next, anticipating the arrival of each minute. Some brave souls in New York and at the Tate Modern in London even undertook to sit through the full day.

2016

The TikTok Feed

TikTok took the cinematic montage and extended it infinitely by creating a continuous feed of short, snappy, user-generated video clips from all over the world. In the app, quick cuts set the pace; most shots stay on-screen for mere seconds, if not fractions thereof. The eye is never bored. The feed offers a deluge of new visual information, and if any one video doesn’t immediately appeal, the user needs only swipe up to skip to another.

The app’s biggest innovation was making its feed almost fully algorithmic. This means that it tells you what to pay attention to, instead of relying on you to curate your own feed. Attention is the algorithm’s primary metric; the longer you watch a video, the more videos of that genre you’ll see. It’s the subconscious extruded into app form, your hidden desires coming to the surface of the feed.

ChilledCow

2017

lofi hip hop radio—beats to relax/study to

The search engine–optimized name of this YouTube channel says it all. It’s a 24-7 stream of music that is relentlessly chill, a mélange of soft drum loops, fuzzy synth melodies, and intermittent atmospheric effects, like samples of rain. The channel pioneered an entire genre of music—there are now YouTube tutorials and online classes on how to compose lo-fi hip-hop beats. The second part of the name clues you in to the purpose of the music: it’s meant to provide an unobtrusive sonic background for relaxing or studying, a soft mental blanket that occupies just enough attention to keep boredom from creeping in. It’s elevator music designed for the twenty-first century, with digital life as a never-ending ascent.

The musician Brian Eno, who coined the term ambient music, describes the genre this way: “It must be as ignorable as it is interesting.” Lo-fi beats tend toward the ignorable side—the drums plink in a consistent pattern and the rhythm never changes. But the beats do hold interest in the play of textures: the different varieties of digital static, the slight shifts in mood, whether happy or subdued. More interesting still might be one’s fellow listeners: On the sidebar of the YouTube channel is a chat stream where people complain about doing homework or hitting a deadline. You are never alone in your neutral tedium.

Laurel Schwulst and Soft Works

2019

Flight Simulator

Escaping the internet has long been one of the joys of air travel. When the plane locks its doors and rises to cruising altitude, all phones are disconnected. Sure, you can purchase the in-flight wi-fi, but it’s usually spotty. Pick up a book or magazine from your bag and savor this rare chance to concentrate. Do a crossword. Gaze at the clouds. Fall asleep.

The smartphone app Flight Simulator, something of a digital design toy, approximates this blissful state of disconnection. You choose a destination, turn on airplane mode, and keep it on for the duration of the actual plane ride. An algorithmic gradient on the phone screen approximates the view from the window. For these precious hours, and without the real-world fatigue of actual travel, your mind is free. But if you take your phone off airplane mode and succumb to distraction, the flight turns around.