Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe is malleable: literary Play-Doh for the craftily minded. As our sapient narrator, he is a lens through which we see the squalor of modern Los Angeles. We know he’s morally rigid, like an animated slab of unwritten commandments, inextirpable in his personal and political proclivities. He doesn’t take money if he finds a job unethical; he doesn’t respect corrupt police or politicians, regardless of their motivations; he doesn’t sympathize with drunks or wife-beaters; he doesn’t like the rich but he doesn’t weep for the poor. He’s a well-worn scourge of complications and intricacies, his own Osiris.

Howard Hawks and William Faulkner gracefully and loyally translated Marlowe to the screen for The Big Sleep, just seven years after the novel’s initial publication. By 1946, Chandler’s books were growing in stature, and American cinema was suffused with film noir, so the character was already relevant; he didn’t need to be modified. By 1973, though, Marlowe and his hard-boiled kin were forgotten, irrelevant, so naturalist auteur Robert Altman had a few changes to make. If Hawks’s Big Sleep is the archetypal faithful Marlowe film, Altman’s adaptation of The Long Goodbye is the archetypal modification: characteristically syncopated and opaque, both satire and homage, poison love letter to a genre and inside joke to its enthusiasts.

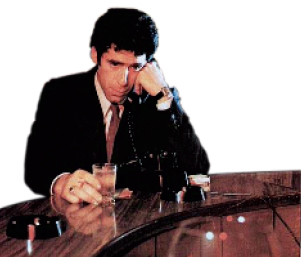

Chandler’s Marlowe thinks fast, talks faster, takes a punch like a champ. He’s invidious, antagonizing authority figures into socking him; once he sees how they throw a hook, they don’t get the chance to land a second. Altman’s Marlowe wears wide lapels and talks to his cat. He ponders his own sad, solipsistic musings because no one else will. He’s out of touch, out of his element, caught in the slipstream of modernity. Altman steeps him in voyeuristic discomfort, the camera drifting and floating and suddenly zooming, never content to stay still. The camera’s constant activity underscores Marlowe’s desuetude, makes him even more pitiable.

The Long Goodbye, Chandler’s longest and deepest novel, dissects the life of a private eye: the boring parts, the tormenting parts, everything in between. It’s more social commentary than noir, with a thread of dubious mystery holding the narrative together. Corruption, sinisterly sunny L.A., big men throwing their meaty bellies around, slamming hairy knuckles on desks, pounding shots of cheap whiskey to

euthanize the slivers of passing morality. Marlowe is our tour guide on a joyless ride...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in