The word machine stands out each time it appears in Masande Ntshanga’s latest novel, Triangulum, suggesting the predestination that’s so inherent in novels—they’ve already been written; their endings are already determined—that mentioning it scans as pedantic. But what happens when the reader is aware of the book’s machinations, swept less into the molded narrative and more into the readymade task of piecing it all together?

Triangulum is a story of voids: a mother, an emotionally gaunt father, and narrative motives whose absence the reader must make peace with. The novel opens with a metafictional conceit: In the future present (2043), a retired South African professor and sci-fi writer named Dr. Naomi Buthelezi pores over half-century-old manuscripts and recordings, trying to figure out if and how they presage her present. These texts—including a teenage girl’s memoir about her search for her missing mother, and a work of dystopic autofiction that takes place in the decades after that search—form the book’s heart, functioning as both a coming-of-age story and a mystery rooted in a post-apartheid South Africa that is still overcoming the scars left by a discriminatory government. The memoir’s narrator wrestles with her sexuality and relationships in a racially stratified society; meanwhile, she’s beset by visions of an enigmatic machine that’s either a hallucination or a message from outer space. Years later, she traverses love affairs, underground political organizations, and ecoterrorist machinations in her work for a governmental data-mining operation. Opacity hangs over these events; along with Dr. Buthelezi, we wonder whether the manuscripts are stories or premonitions.

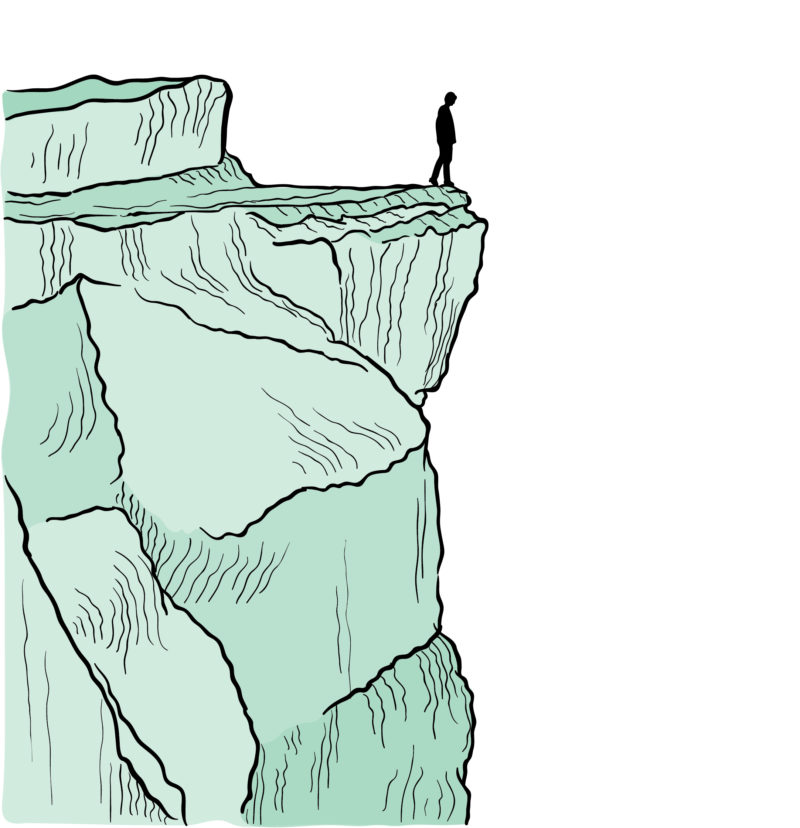

It’s said that the last sentence of a chapter often hangs as if from a cliff. If you know the height of that cliff and the angle from which you can see the next chapter, you can know where that chapter will begin. The sentences at the ends of Triangulum’s chapters do not hang. They curl and spiral, wrap up only to unravel, and only seem to hold stable meaning. Thinking of her recently deceased boss at a governmental organization, the mysterious narrator closes one chapter “imagining him like the rest of us, a configuration of chemicals and flesh burdened by consciousness—which I thought of as a vague collection of ideas, both cumulative and transient, running the motor of a warm and wet machine.” These sentences are in flux; they sink into their own beauty, the winding language...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in