Detail from a promo copy of Albert Ayler’s Bells , courtesy Ayler.co.uk

Detail from a promo copy of Albert Ayler’s Bells , courtesy Ayler.co.uk

I. Night of the Senses

There are a couple of early snapshots of me and my father that I haven’t seen in years, thanks to my mother’s inexplicable embargo, in place for well over a decade, on the display or exhibition of family photos. These snapshots are black-and-white in the unselfconscious manner of 1963; I believe the date, not that I’d need it, is stamped on the border of each. In both, I’m sitting on my father’s lap in one of the raggedly covered armchairs I vaguely remember from our old apartment on E. 13th. In one, he’s bending toward me, no doubt telling me something; in the other he’s holding me balanced on his knee, and appears to be commenting to someone off to one side, invisibly beyond the lefthand frame of the picture. In both pictures my face displays the delight that I have always associated with being in my father’s presence.

My father rather famously loved jazz, particularly bebop and hard bop, though his interest extended well into the range inhabited by the likes of Albert Ayler (I can recall evenings when my mother lit out for the shelter of the bedroom as the transparent disk on which Ayler’s spooky Bells had been pressed rotated on the turntable in our living room). He listened to music every evening, at the end of his working day. On Friday nights—hamburger night, in my parents’ particular system of rituals—my father would stand guard at the entryway at the top of the stairs, the front door open to allow the greasy smoke to escape the apartment, with a cigarette and a bourbon over ice in his hands, the volume cranked so that the music banged up the narrow shaft containing the poured concrete steps of our apartment.

Among the many thousands of things my father told me—because in a sense his every action was a sort of enjoinment to me—was to love jazz too. Thelonious Monk was my favorite for a long time; through him I acquired a taste for dissonance, for the slightly skewed approach, that I’ve never lost. For a while I borrowed from my parents a 10” Monk LP with the irresistible title of Genius of Modern Music, and I would space out in my room listening repeatedly, in particular to the stupefying collaborations between Monk and Milt Jackson on cuts like “Epistrophy,” “I Mean You,” and “Evidence.” When I was around twelve, though, I decided to get some records of my own and I became the only kid at I.S.70 to go out and buy Thelonious in Action, a recording of the Thelonious Monk Quartet live at the Five Spot in 1958. (My parents may well have been there, though not together. My father’s first marriage was unraveling at the time, and while I don’t know what stage my mother’s marital woes had reached, I do know that her husband then was a man she has never referred to as anything other than “poor old George Bradt,” a reference so liturgically consistent that I think of it as the man’s true and complete name, so dismissive that I can never fully form in my head the idea of my mother’s marriage to this cipher.) John Coltrane had left Monk’s band by then and was replaced onstage by Johnny Griffin, a tenor man who’s never entered the pantheon alongside Trane, Sonny Rollins, or Dexter Gordon. He was a good, hard player, though, and ballsy enough to include on his debut album a rendition of “Cherokee.”

“Cherokee” was the song on whose bones Bird built “KoKo,” the tune my father claimed had changed his life. “Great blasts of foreign air,” as he put it. “Foreign air, the whole wide world entering the house”—the house, the block, the neighborhood of Bay Ridge that, to hear him tell it, he’d escaped like a refugee; the neighborhood where, sixty years later, he died alone in a bed in a podunk hospital, of lung cancer from the cigarettes he’d started smoking right around the time that he’d first put on that 78 by “Charles Parker and His ReBop Boys.”

Charlie Parker, courtesy Alamy

Charlie Parker, courtesy Alamy

Introducing Johnny Griffin and Bird/The Savoy Recordings were two of the twenty-five or so CDs (that may have been all I owned back in 1990) that came with me when I split with my girlfriend and quit my job and left San Francisco to set up as an Official Writer in Williamsburg. I worked at the kitchen table, writing in longhand in black marbled composition notebooks (a conceit I’d picked up from my father) and then typing up the day’s work on my Brother AX-12 Studentwriter, a toylike machine that nevertheless devoured typewriter ribbons with professional inefficiency. I would write frequently and at length to my father (so that was where the typewriter ribbons were going), pissing and moaning about my slow progress and about the state of letters generally, impatient correspondence to which my father responded with forbearing support. He sent me lists of books to read. He tolerantly critiqued my work, and equally tolerantly responded to my own juvenile critiques of the western canon, which I was throwing myself at each evening from the wing chair in the living room.

Sometimes I’d put down the book I was reading to concentrate on listening to one of those CDs. Often, I would pick The Best of Sonny Rollins, a compilation of Blue Note recordings Rollins made before his famous woodshedding retirement in 1958 to the pedestrian walkway of the Williamsburg Bridge, whose towers I could see from my bedroom window. I succumbed to the familiar false syllogism: Rollins was a genius who woodshedded, I was woodshedding (i.e., I couldn’t get my juvenilia published), therefore I was a genius. It soothed. My favorite song on that album was “Striver’s Row,” whose title, in that year of ambitious decisions and changes, thrilled (though I still haven’t visited the Harlem development that lends the song its name), a tune that begins with syncopated beats bouncing off the skins of Elvin Jones’s drums, an intro from which Rollins’ saxophone seems to explode like a million pounds of high explosive from the muzzle of a cannon. This is jazz stripped to its voodoo essentials—a drum, a bass, a saxophone; the basic vocabulary of percussion, sonorous rhythm, and the high jittery shred of the melody. I sat and listened until late, often, sometimes because I couldn’t sleep—massive refrigerated poultry trucks, up from the Maryland shore, would rumble onto the block early each weekday morning and idle their engines for hours until the wholesale market across the street opened for deliveries—and sometimes because, having removed myself from the daily business my life had consisted of for some time, I was trying to project myself into an imagined future space, asking myself: Where the hell am I going?

It turned out that, via a couple of detours, I ended up in another part of Brooklyn, with a wife, and two kids, and two published books, and many friends acquired in the intervening years, and my parents in New York and a half-hour away after decades in California, and so it seemed I’d found not only the space I had been imagining in Williamsburg and subsequently, but a continuum—the comforting adjacent elements remained constant, and things could only get better and better as I moved forward.

Sonny Rollins in 1957, photograph by Francis Wolff

Sonny Rollins in 1957, photograph by Francis Wolff

Every now and then I take it into my head to smile at an institutional camera—the DMV’s, say—and the resulting photo invariably seems to expose a certain amount of the delirium that I imagine is always lurking within. I joined the YMCA the day I found out about my father’s illness, so there’s actually a picture I can gaze at that shows me—or, rather, my demented double—on the last day my assumptions were intact, grinning insanely just a little while before I phoned my parents and my mother advised me that an MRI had revealed a “significant” mass at the base of my father’s brain. The demented twin’s hour was about to come.

The news unhinged me—that is, it managed to unscrew every working part inside me. I startled my wife by weeping, openly and uncontrollably, on five successive nights after the kids had gone to bed. Following the diagnosis came neurosurgery, following the surgery came an additional diagnosis (metastatic lung cancer), following the additional diagnosis came a prognosis, following the prognosis came treatment, treatment, treatment. My wife lent her devoted support. My daughters remained oblivious to the seriousness of the thing, which was calming. I retreated into the comfort of my family, my apartment, my belongings, my books, into simple soothing reliability. All the mechanisms, the routines, the failsafes, the backups, that I’d painstakingly built into my life swung into effect, operating flawlessly. That was the plan. If I was unhinged, they worked just fine. That was always the plan. Gradually I fastened all the working parts back to one another. Gradually I became used to the idea of my father as a patient with a grave illness. I began walking the earth as something other than a gigantic abraded wound. I quit smoking. I went to the Y every morning to swim. And then I decided to destroy everything.

It’s possible that every day the opportunity exists to seize the realization that you’re not the good person you may start out thinking you are—through every venial act, every spasm of ungenerosity, every occasion of sin not shunned—but for me the realization came all at once, when I found myself some time later standing nervously in the doorway of my parents’ kitchen, having literally backed away from the table where they’d been finishing up their lunch—my father slumped tiredly in his chair, his mostly-untouched food before him, my mother standing frozen at one end of the table, staring at me—informing them that for the previous month I hadn’t been living with my wife and children; hadn’t, in other words, been living at home. I’d fallen in love with a woman, another man’s wife, irresistibly, with startling swiftness and thoroughness. I also had discovered in myself reserves of deceitfulness, immorality, and, finally, cruelty that our happy secret afternoons together could only temporarily paper over.

These were some bad times, full of—well, they were just bad. And friends withdrew from it all, or from what they saw as a possible source of contagion, or simply from someone who was less lucidly predictable than they required. But redemption, of a kind, was at hand: illogically or not, our affair was justified in a sort of back-formational way by the news of this woman’s pregnancy, which seemed to put a seal on this momentous and unexpected shift. It was a boy, as it turned out, and what appeared to me to be the symmetry of preparing to welcome a son as I was preparing for my father’s departure from the earth was, again, soothing. I thought of those snapshots. That look of delight.

Lying in extremis, the night before he vanished into oblivion, my father, struggling to speak, told me, “I’m sorry I’ll miss your son.” I responded, in one of the marvelously stupid equivocations I’d become so good at delivering, “Not necessarily.” But of course I knew it to be true: he would miss my son.

II. Night of the Spirit

As it turned out, we all did. On a warm spring morning about a week after he died, I submitted to a paternity test—a mere formality, I was more or less assured. There were issues that needed to be addressed, the usual kinds, concerning legal responsibility and child support; as well as more emotional ones that needed to be put paid to. We went to one of those older midtown office buildings near where B. Altman used to be that seems charming from outside and is tawdry within. We rode the elevator to an office that, oddly, was part employment agency and part DNA test administration center and after an awkwardly funny mixup—the receptionist queried us about the “job” we’d come about—we went into a small and shabby exam room where a technician checked our IDs, asked us to fill out some forms, took swabs from the insides of our cheeks, sealed them in plastic bags, took a Polaroid photo of us—I remember that we’re both grinning like fools in the picture—sealed everything inside a larger plastic bag, and then sent us on our way. I felt official. My saliva was on its way to a laboratory in Ohio.

About three weeks later two identical envelopes arrived at our apartment, one for each of us. Return address, “205 Corporate Court.” They looked like credit card solicitations; I nearly tossed them without opening them. According to the Test Report within, prepared on June 6, D-Day, the probability of my paternity was 0%. “The alleged father,” the report said, “is excluded as the biological father of the amniotic sample obtained from the mother. This conclusion is based on the non-matching alleles observed at the loci listed above with a P[aternity] I[ndex] equal to zero. The alleged father lacks the genetic markers that must be contributed to the child by the biological father.” Thus was resolved case number 276919.

And thus we entered a dark period. There were a lot of all-night conversations in the aftermath of Corporate Court’s sterile revelation. An apparitional grief overtook me—I’d lost someone I’d been ardently anticipating, but the fact that he had never actually existed seemed both to delegitimize (so to speak) my emotions and to force them underground. I had to compel myself not to think of the unborn boy as the homunculus of his father, who—I was bluntly informed—would henceforth act in all respects as his real father, both prenatally and in that impenetrable complication called the future. My own role was mine to define in whatever interstices I found between the woven strands of guilt, shame, propriety, morality, ethics, and legality. In other words, I could go fuck myself.

For the second time in a month I realized that our fate, always, is to finally reach the point of convergence where reality and our arduous resistance to it meet, and reality wins out despite our most compelling argument against it; because as brilliantly as we may rise to the occasion at this convergent point, we argue against it the way a crazed mathematician might argue against the number 2—maybe it’s not really a prime, maybe it’s not really even, have we considered this and have we considered that, etc., etc.: we’re making sense only to ourselves, and while the killing awareness is there that the persuasive bit of nuance thrives right at our fingerprints, it’s there invisibly, untranslatably. “One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.” So wrote Scott Fitzgerald, referring particularly to his lost youthful ability to muscle, by force of will, reality into the rough form of his plans. The fact is that while it seemed, and seems, to me that there was more to the argument than simply the matter of the contribution of requisite genetic markers (Did I think of my father, as I stood over his wasted corpse at Victory Memorial Hospital, “He contributed the requisite genetic markers…”? Had I thought of that while I sat balanced on his knee when those snapshots were taken 43 years earlier?), the truth was blunt and definite enough to preempt subtlety.

It was during these tearful and angry discussions, these detonations of confusion and blind will that took place during the hours Fitzgerald spoke of figuratively when he referred to the “real dark night of the soul,” when I noticed the bird living in the tree next door.

This is a tree-lined block, a pretty block, the nicest I’ve ever lived on in New York City. The trees are home to families of birds, birds who cry out intermittently throughout the warm days but whose calling is most especially apparent in the mornings as the sun begins to appear over the housetops and in the evenings as it sets. This particular bird was alone; he would start up usually around sundown and would keep at it throughout the hours when, ordinarily, I would have spent my time unconscious. He was a haranguer, a heckler, with a series of different calls that he would cycle through, sometimes in a strict sequence, other times seemingly completely at random. In those middle and late weeks of June his evening and nighttime addresses were a constant. It was when, for the second or third time, he burst from silence into song as I approached the house on the street—joyous? warning? who knows?—that the comforting certainty came over me that this animal was my father. Why not a subversion of natural law? Not a single one of the constants I’d relied upon remained: I’d left my beloved wife, I no longer slept in the same house as my beloved daughters, my beloved father was dead and blasted to ashes, my beloved son had been replaced by someone else’s genetic markers, and the beloved woman who seemed to shimmer at the center of all these changes, a woman clothed with the sun, had become intractably remote. A supernal visitation? Why not? The more I thought about it—and you may rest assured that it is perfectly commensurate with my state of mind then that I devoted a good deal of thought to the possibility—the more it seemed as if it had to be the case. Natural parodist, long-winded, telling the same stories over and over, entrenched in a comfortable routine: even if this bird wasn’t my father, he definitely was. And of course there was Parker’s nickname, Bird: irresistible, trite, irresistible.

My mother asked me if I ever felt that my father was with me. She told me that she felt him in the bedroom, sometimes; that she would catch a glimpse of him in the kitchen and while she would then realize that it was just a shadow, or an apron hanging from a hook—the way that a pair of boots in the corner might momentarily appear to be the ginger cat you’d had put down last month—she knew, ineffably, that it was my father. He wanted her to be all right, to let her know that it was all right, she said. I, for whom nothing was all right, eagerly told her about my bird, but she shook her head: “That’s a mockingbird, Chris,” she told me, as if the ghost I had conjured was grievously delusional compared to her own comforting perceptions.

He went away, finally. I’d like to say he rode me through the crisis, but although hearing him made me feel less alone than I might have felt at this time when I felt the extraordinary aloneness of the man to whom ordinary life has become a stranger—he was, as Edward Dahlberg wrote, “the immaterial food we need when we are a wilderness”—I think that as my father often did when he felt that he’d reached the limits of his influence over me (I clearly wasn’t going anywhere, if his plan was to perch in the tree next door and sing “get out get out get out get out nownownownow”) he just knocked it off.

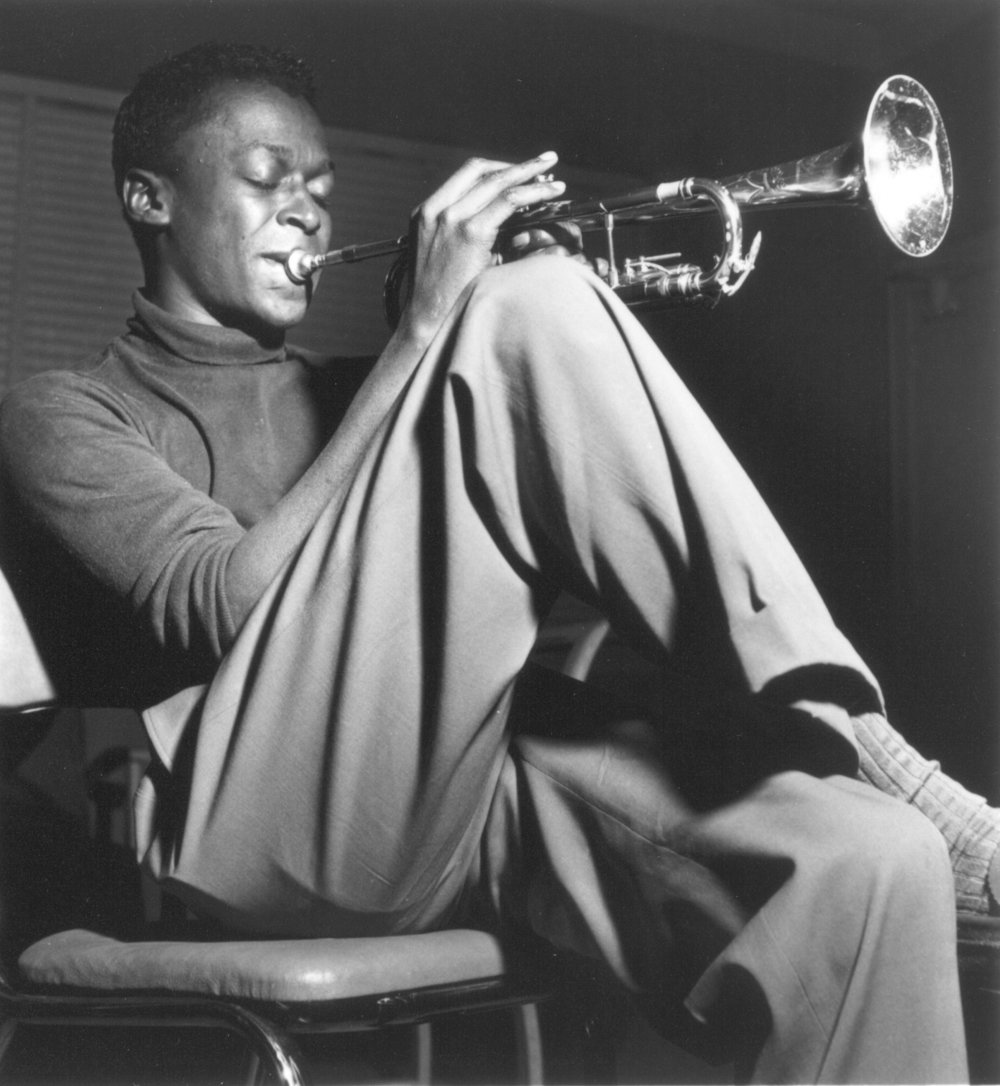

One song that makes me cry each time I hear it is Miles Davis’ version of “Bye Bye Blackbird.” His trumpet moves once, thinly, through the sad changes, acknowledging the melody, and then through ensuing choruses defies it; holding the notes close, bending them into blue patterns. He lays out, and is followed by Coltrane—another man denying the tune’s invitation to sorrow, his variation on the song inimitably dense, clustered tones filigreeing the tune, gently mocking it, building more on the changes than on the melody: both men working to keep the composition from moving down the scale into the sad refrain like two friends joking over their respective unbearable losses, trying to cheer themselves up, to avoid bursting into tears. Red Garland begins his solo in the same spirit; his right hand seems to hit the keys one at a time, dryly, with restraint, but then six and a half minutes into the song he repeats a figure twice and then breaks everything open with a lush chord progression that concedes the mood totally, Philly Joe Jones and Paul Chambers swinging into an oom-cha! vamp behind him; he not only descends into the heart’s well of the song but finds the inarticulable loss of the world afloat there, the sum of all parts put into motion when jazz is working, the fact that sadness is not necessarily a state unto itself but a progression whose onset involves the surrender of joy—joy and hope escape that solo like the final exhalation of one’s life. It is, after all, a farewell.

Miles Davis in the 1940s, photograph by Francis Wolff

Miles Davis in the 1940s, photograph by Francis Wolff

Christopher Sorrentino is the author of five books, including Trance, a National Book Award Finalist for fiction, and The Fugitives, recently published by Simon & Schuster. This piece was originally published in Moistworks.