There is a man in the Oval whom I refer to as the Mayor. I see him with his Jack Russel terrier, Lucky. He runs, he stops, he lifts Lucky into the air, raising and lowering the dog several times, as if his pet were a kettlebell. I envy not merely his energy but his extroversion. It appears that anyone who enters this park—Williamsbridge Oval, in the Bronx—is greeted by the Mayor. For a period, he greeted me too.

In the case of the Mayor, I cannot identify which of my ungracious behaviors elicited his silence. I did not assist in a scheduled clean-up of the dog park on a Sunday, despite having two large dogs who regularly romp around and shit in it. I also passed on picking up a spare rake, this after the Mayor had gestured to me to lend a hand, the Mayor himself already hard at work scraping the fallen leaves off a hill. And no matter how much the Mayor pleaded, I never called the city to report that the streetlamps failed to come on at night in the Oval.

“But maybe,” my wife said, “before we leave the Bronx, you can do something on behalf of the community. Well?”

“I will interview the gardeners,” I said. “I mean, my interview with the gardeners will honor the Oval. Elucidate nuances of the Oval. The Oval is a microcosm of the Bronx, in spirit and in vulnerability. The gardeners, who will talk to me, encapsulate this too.”

In anticipation of my interview with the gardeners, I purchased a copy of The Education of a Gardener by Russell Page. Page, a renowned gardener and landscape architect of the twentieth century, accessed a new world—the world of gardening—when, at the age of fourteen, he “wandered off to the flower-tent” at a local agricultural show and discovered Campanula pulla, or blue drops. This was my first question to the Oval’s gardeners, Andrea Gaskin and Ron Bucalo. As we sat on separate benches, surrounding what Ron referred to as the fairy garden, where bulbs of blonde allium looked like incandescent Tinker Bells, I wanted to know who or what had led Andrea and Ron to gardening.

ANDREA GASKIN: My father had a petri dish—I was about five—this was in an apartment in Harlem—and he gave us a kernel of corn and a kidney bean and some cotton. He put it in the petri dish, put the seeds underneath the cotton, and told us to keep it moist. He told us to watch it every day. I would watch it and, lo and behold, a baby plant came out of it! I was hooked! Really, from that moment, ’til now, I’ve been hooked on growing plants from seeds, from propagation, from cuttings, from divisions.

So, in adult life, I worked for the Central Park Conservancy. I was like a groundskeeper. But I kept sticking with the gardeners and learning what they were doing. I would ask them, ‘Can I weed your section?’ Nobody’s going to turn that down. Or, ‘Can I prune?’ I would sit at the gardener’s table at lunch time and listen to whatever they were talking about. Then when the positions became available at the Parks Department, I got a phone call. But I wanted to be at Central Park. So I never applied. I got another phone call, ‘Did you apply?’ But I was looking for a position in Central Park. I wasn’t really looking for a position in the Parks Department, and especially not in the Bronx.

RON BUCALO: My brother and I were forced—to help my father in the backyard. We were forced to help my dad. So therefore he was shocked one day when I called him, down the road, many years later, ‘Hey, Dad—I’ve got a new job.’ He goes, ‘What do you mean a new job? You’re an artist.’ I go, ‘Well, I had to go beyond that now.’ Because, uh—I’d been an illustrator for thirty years. I worked for Walt Disney, Sesame Street. I’ve done thousands of books and magazines. But the art field started to dry up and my wife wanted to go back to school and suddenly the art was no longer cutting it. I was told by somebody that they were looking for a gardener in the Bronx. I interviewed there. And I knew enough, thanks to my dad, to where I got the job to become a gardener.

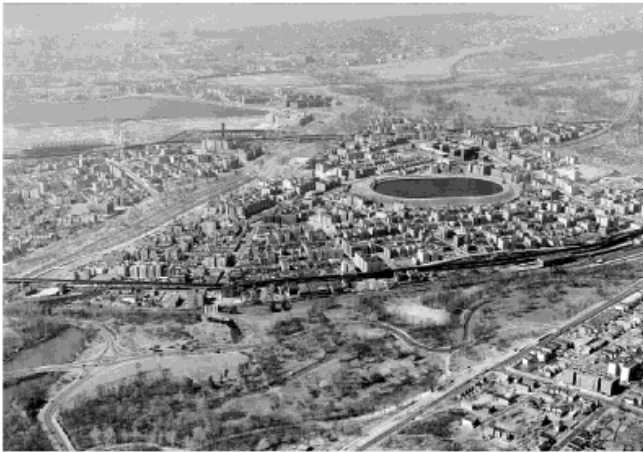

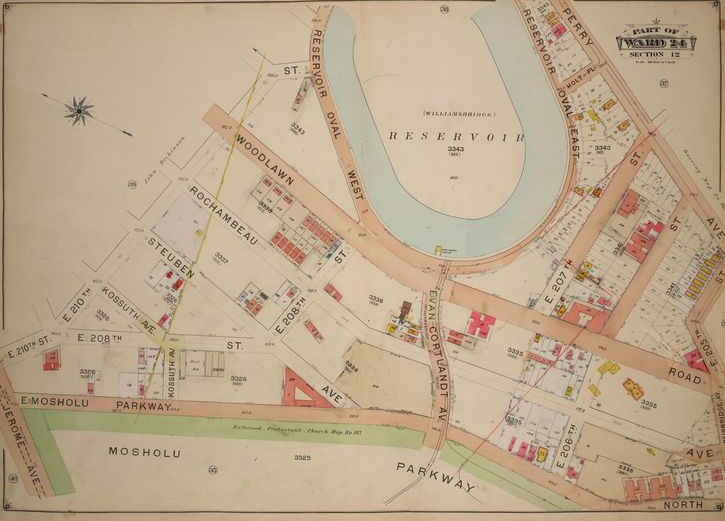

While interviewing Andrea and Ron, I thought less about the Mayor and more about Page’s preferences, including: “If I were to choose a site for a garden for myself I would prefer a hollow to a hill-top.” The Oval is a hollow. The park is concave, made up of two rings. One ring is at street-level; it is a paved walking path, garnished with benches. The other ring is twelve-feet below it. Here, there is a running track, as well as tennis courts, playgrounds, a fountain, and a new smooth, plastery skate park. On both levels, there are gardens.

The hollowness of the Oval is a function of its former life as a reservoir. Williamsbridge Reservoir, completed in 1889, relied on the Bronx and Byram Rivers water system; the 120-million gallon reservoir facilitated the swift development of the Bronx, particularly the borough’s western section, where newly tall buildings required an adequate water supply in order to meet the demands of superior water pressure.

THE BELIEVER: On walks with my dogs, I frequently notice you manipulating yards of hose—seeing as what you have to go through in order to hydrate your plants, it’s ironic that this site was once a reservoir.

AG: Oh, my god! That’s so true.

RB: See, here it’s not so bad, because you hook up two hoses—

AG: Four. To get from downstairs, up the stairs, across this path over here, and to get to this garden. Four hoses.

RB: But other than the hoses, we have these giant plastic containers that we can fill up and we put them in our go-cart and we can push that around. See, we asked for a wagon. They didn’t have any to give us, but they gave us four loose wheels and a green basket. Well, little did they know, they were dealing with, like, an ex-go-cart maker from way back as a kid. So I got the axels, the cotter pins, the two-by-fours, and just made a go-cart. Now we’re good to go. And if we ever want, we can ride down the hill in it.

AG: Actually, for us not to have running water up here—it’s a big deal, but it’s not something that I haven’t seen before. When I was a kid, my father bought us a summer home that had no running water. It was a trailer, in Delaware County. It was the most wonderful experience. It was like Laura Ingles Wilder. I just loved it. So not having water here is not going to kill me. And it makes me more capable of keeping plants alive than, say, people who have never really had to struggle.

By 1925, Williamsbridge Reservoir had been drained—Jerome Park Reservoir supplanted it—and in 1934, Robert Moses negotiated the transfer of the reservoir’s land to the Parks Department through a process of “reassignment.” The transformation from reservoir to park was made possible through the Works Progress Administration, a feature of Roosevelt’s New Deal. On September 11, 1937, Williamsbridge Oval Park was officially opened by Moses.

Moses, whose obituary in The New York Times said that he “played a larger role in shaping the physical environment of New York State than any other figure in the 20th century,” was known as the master builder. He was also, in a sense, the master gardener—not to mention the master destroyer, with his expressways razing low-income neighborhoods and leading to the destruction of New York’s only remaining freshwater marsh, also located in the Bronx. From 1934 to 1941, Moses claimed that his department had created an additional 2,500 acres of parkland through landfill. Indeed, the floor of Williamsbridge Reservoir was raised to twelve feet below street level via landfill. Landfill, also known as reclamation, is like a kind of compost insofar as it is a mixture of waste material—dirt, trash, and construction debris—which can function as a growing medium; in this case, as a medium for the growing of parks.

I contemplated Moses in the context of The Education of a Gardener. “You design a garden within all the limitations of a site, of a client’s requirements, the climate and the nature of the soil, of the local culture and of your own capacities as artist and technician.” For Moses, like Page, these variables acted as limitations. Unlike Page, Moses did not design New York State within them. Rather, Moses mostly ignored anything, and anyone, that impinged on his ambitions. The Oval, however, was different; its fate did not go according to Moses’ original plan. Moses had initially wanted to construct an outdoor sports stadium on the site, with courts in the center “that could also be used as a parking lot.” Resistance from “the local culture,” however, forced Moses to settle for a park. Before there was the Mayor of the Oval, there was Cyrus Gordon, who, representing the Williamsbridge Civic Association in a meeting concerning reassignment, noted that the reservoir was “located in the centre of a restricted residential neighborhood in the immediate vicinity of a number of institutions, including the Montefiore Hospital and Home” and “that the gathering of large and noisy crowds in the stadium would seriously impair the efficiency and usefulness of the hospital as the rest and quiet of patients, doctors and nurses would be disturbed.” If the reservoir were to be assigned to the Department of Parks, Gordon concluded, it must “be made subject to restricted use for truly park purposes.”

In the Oval, Andrea, Ron, and I discussed the favorite plants of the park’s patrons. Compliments, said Andrea, were regularly being paid to Gomphocarpus physocarpus, or “hairy balls:” a bulbous, stubbly milkweed.

BLVR: Page, addressing the public gardener, writes: “Remember that one of your aims must be to lift people, if only for a moment, above their daily preoccupations. Even a glimpse of beauty outside will enable them to make a healing contact with their own inner world. Nor must you ascribe such an idea to sentimentality. It is one of the most valid reasons for gardens and for gardeners.” One objection to the proposal of constructing a stadium on this land was that a stadium would undermine healing, that its accompanying raucousness would upset the recovery of patients at Montefiore, for instance. Have you had any park-goers report experiencing restorative effects from visiting the gardens at the Oval?

AG: There was a woman. She said she was going through a lot—she said she had excruciating headaches. She was going to therapy, but it wasn’t really working. She came in here, and she saw a garden she didn’t expect to be here. And she said, ‘You know something, this is horticulture therapy. To come to this park.’

RB: Who was it? Silver? The [Parks] Commissioner? He basically would always say, you know, you’ll have a person coming into the park that’s maybe going through a really tough day or something’s going on in their life or whatever, and seeing something in the park with color can really lift that person’s spirit. If only for a moment.

AG: And the things that you don’t think that people notice—people really pay attention. They observe. There is something actively going on, and it’s exciting and they might wonder, ‘Okay, what’s coming next?’ Or they might think, ‘Oh, this is great.’ And then I tell them, ‘Oh, there’s more to come!’

One virtue of a park in the shape of an egg is that the walks are circular—you are able to pass life and people again and again and again. There are additional chances. After my interview with Andrea and Ron, I saw the Mayor.

Hello, Mr. Mayor. If it weren’t for people like you, like Cyrus Gordon, like Andrea and Ron, there wouldn’t be a park. There would be a parking lot, but no park. And then what? The Oval is Norwood’s backyard. Everyone comes here. Where would the people—the community—go without people like you? With people only like me? I’m sorry.

I never said this to the Mayor despite passing him multiple times ahead of departing New York. Instead, during my final dog walks around the Oval, I was made repeatedly aware of the privilege of silence, in which I indulge. I can speak but I often choose not to. In the Oval, I passed parked cars in which police officers the color of cornflowers were planted; they did not address me, and I was not forced to address them. I was in a position where I could choose my words like Page could choose his flowers. Page, who was trained in the 1920s as a painter at the Slade School in London, acknowledges that he has never been responsible for the design or planting of a public park, which he describes “as one of the most difficult exercises in landscape gardening.” Although he does not state exactly why public parks are such tricky exercises, access to resources is one factor that complicates their realization and maintenance. The resources available to Andrea and Ron, as evidenced by the lengths they must go to in order to water their gardens, are undoubtedly fewer than what Page had at his disposal when, say, he was sculpting the parterre at Longleat House, in Wiltshire. A public park, furthermore, speaks to and for a community. Unlike a private garden, it has the added responsibility to be forever in conversation with the public. When viewed from above, the Oval resembles an open mouth.

The water of the Bronx River was not always undrinkable. But then European settlers arrived and a bleachery was installed along its banks in the early 1800s. Moses was part bleachery, at least insofar as he bulldozed Black and Latinx homes on behalf of highways and parks, displacing persons of color and thereby whitening the cityscape. In the wake of pollution and Moses’ “urban renewal” projects, community organizations like the Bronx River Alliance and the Bronx Defenders—a public defender nonprofit—seek justice. A Green New Deal would serve the Bronx now—the Bronx being New York’s poorest borough, with an unemployment rate of fifteen percent—as a New Deal served the borough then.

Just after I turned off my tape recorder, Andrea said, “You know, I don’t really want to go to Manhattan as a gardener anymore.”

“Yes,” I said. “I don’t particularly want to leave here either.”

“I’m happy here,” Andrea said. “Because it’s this park. It’s easily accessible and I like the patrons.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, as I thumbed my phone. “Could you please repeat that?”

“This park,” Andrea said, “is what we imagine it to be.”