Originally published in 1989, RE/Search Publications’ Modern Primitives turned out to be far more popular than anyone could have expected from a book about tattoos, piercing, and ritual scarification. The body modification anthology helped drag the very idea of tattooing out from the world of bikers, sailors, and indigenous tribes, and thrust it deep into the hipster mindset. Just a few years after Modern Primitives was released, legal tattoo parlors began cropping up in suburban shopping malls, and body art went mainstream, with tattoos becoming as commonplace as pierced ears.

For over a decade now, the FBI, working with a number of independent contractors, has been trying to develop a foolproof facial recognition program to pick would-be terrorists out of a crowd. While far from perfect, facial recognition technology has advanced far enough to be picked up and implemented by Apple, Google, and various local law-enforcement agencies around the country. Meanwhile, iris scans, considered the next generation of fingerprint identification, has become almost commonplace in corporate and federal office buildings as a first-level security measure despite precious little supporting evidence our irises are as unique as claimed.

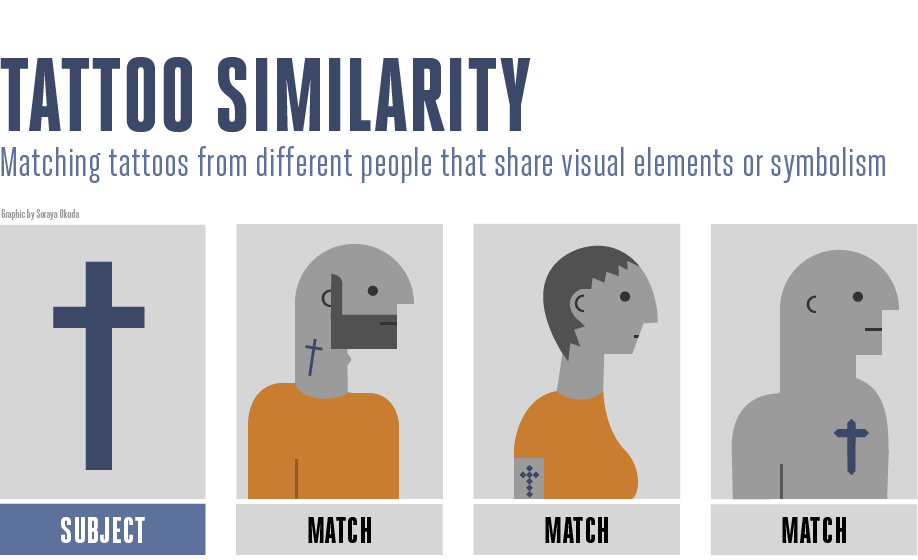

The next evolutionary stage in the FBI’s use of biometric identification is at once problematic, ham-fisted, and ridiculous. According to the Electronic Frontiers Foundation (itself now a subsidiary of Google, which is worth keeping in mind), since at least 2015 and perhaps earlier, the FBI’s Cryptanalysis and Racketeering Records Unit has been building a database of tattoo designs.

Tattoos, like scars, moles, and other unique features inscribed on the surface of the flesh, have long been used as a means of identifying both criminal suspects and unidentified bodies. The current motivation is hardly a new one, given for years investigators, employing what they termed TAG-IMAGE, have been using tattoos to finger members of street gangs, organized crime families and white supremacist groups.

Now, however, it seems the goals of the new project are far more ambitious. The FBI hopes to use your tattoos as a means of learning about not only your connection to some larger and undoubtedly sinister organization, but your personal tastes, beliefs, family members, religion and ethnicity. Their ultimate goal in building the database is the further construction of a mobile app which will allow officers to immediately pull up all the information available based on your body art.

The image recognition technology at the heart of the project is already readily available. I’m blind, and so make regular use of several apps, like Tap Tap SEE and Seeing AI. Using any of these apps, all I need to do is point the phone at something—a product on a grocery store shelf, say, or a car or a piece of mail—and after running whatever the camera sees through a massive and growing image and character reader database, the phone will describe it to me. The results are sometimes more precise than others, but I’m often amazed at how accurate and detailed the descriptions can be.

The FBI is envisioning the day when all an agent or local cop will need to do is snap a picture of someone’s tattoo, and in a blink, using a similar app, receive a detailed personal profile.

To date, it’s estimated the FBI has collected some ten thousand tattoo designs, or roughly the equivalent of the number of generic flash-book designs offered at most any mid-sized tattoo parlor in the country.

Working together with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the FBI began collecting tattoo images from perhaps unwitting “volunteers” within the nation’s prison system. In a way the reasoning makes sense, as the prison population would seem to provide a ready supply of affiliation tattoos from gangs both inside and outside the walls, as well as violent political and religious extremists. Religion seems to be of particular interest to the researchers, who to date have focused closely on assorted crosses, crescents, stars and other Christian, Islamic, Hindu, and Jewish symbology.

Of course, beginning with a collection of prison tattoos immediately presented a major hurdle for image-to-image software developers—prison tattoos tend to be sloppy and inconsistent. Instead of using the professional grade inks and electric needles found in most commercial parlors, prison tattoos are more often than not scratched into the flesh with pins and ashes. As a result even basic symbols worn by, say, half a dozen members of an outlaw group might bear a distant familial resemblance at best. Not surprisingly, early tests of the technology revealed only about a fifteen percent accuracy rate when it came to matching symbols.

But that seems to be the least of their, and our, problems. At a presentation before members of the nineteen corporate, government, and academic groups conscripted by NIST to work on the identification software, the director of the Bureau’s program reportedly asked, “What do these symbols mean?” It wasn’t a rhetorical question—they honestly didn’t know, and were after what they termed a one-stop database for symbol interpretation.

What they are apparently after, in short, is part dream dictionary (according to which everyone who dreams of swimming is dreaming about the same thing) and an accurate Swahili-to-Gaelic computer translator.

Instead of bringing on a crack team of semioticians, Roland Barthes scholars and veteran tattoo artists to decipher and elucidate tattoo iconography, the FBI did what pretty much everyone else would do when faced with such a daunting task: they went online and began scouring symbol, trademark and icon glossaries.

They seem to forget that, symbols being symbols, meaning can remain quite fluid depending on the context.

The symbols we’ve come to associate with the Nazis were originally co-opted from a variety of religious, occult, and otherwise mystical and mythological sources, and continue to mean different things in different cultures. Among football fans, an elongated capital “G” is accepted as the team logo of the Green Bay Packers, while elsewhere (like the Star of David) it’s been adopted as a gang tag.

The concern, especially if the FBI is intent on ascribing a single immutable meaning to each tattoo in their database, is the clear possibility of misinterpretation.

The late ManWoman, an artist profiled in Modern Primitives, spent a lifetime trying to reclaim and demystify the swastika by covering his body with two hundred sun symbols from assorted cultures. Would he be able to explain this to an arresting officer whose Smartphone was telling him he’d just nabbed a dangerous neo-Nazi leader? How many wrongly accused Packers fans will suddenly find themselves listed in a database of known gang members, and how many Native Americans will be labeled White Supremacists?

There is precedent for the concern. The EFF recounted a high-profile case from a few years back in which a Mexican man was slated for deportation after the police concluded his tattoo was evidence of gang membership. The judge dismissed the case and freed the man only after a gang expert took the stand and reported he had never seen the symbol before, that it had nothing to do with any gang he knew.

There is also the issue of people branded against their will by gangs and cults, and those who break away but can’t afford the costly and time-consuming tattoo removal process.

Which brings us back to the mainstream tattoo and body piercing craze of the past quarter century.

If the FBI’s goal in creating this one-stop tattoo interpretation app is to in turn build up other databases of known gang members, White Supremacists, immigrants grouped by national origin, terrorists and political and religious extremists, what are they going to do when agents begin encountering common tattoo parlor flash-book designs?

A Totenkopf or baphomet or gang symbols are one thing, but what to make of a flaming skull or a pair of dice rolling snake eyes? What do they really mean? What is the bearer’s dark secret? How to interpret a baby demon farting fire? Does a Tasmanian Devil clutching a hammer in one hand and a beer in the other carry a distinct meaning from a Tasmanian Devil with a hammer in one hand and a joint in the other? Are they icons of two warring gangs? Does that broken cross twisted into an upside-down question mark mean the feds have nabbed a dangerous member of a Satanic child trafficking cult, or just a dopey Blue Oyster Cult fan? And what the hell is the FBI expected to make of all those ubiquitous Celtic tattoos?

Point being, if you were foolish enough to get a Chinese symbol inscribed on your body without being able to read Chinese, you might want to get it translated before you find yourself locked away in some CIA black site accused of being a spy.