There’s a video clip you can find online which was recorded in 1967 as part of NBC’s television special, “Moving With Nancy.” A full moon sits low in a sky clouded by smoke. Strings swell, and the silhouette of a man on a horse emerges from over a cliff. He rides along a ridge and down to the bleached-out brown and blue of the Pacific in fire season. The waves come in, the time signature shifts, the film cross-fades, and Nancy Sinatra appears walking through a field. She advances through the flowers like a woman who can’t quite give herself up to nature. All white mod pantsuit and hairspray and mascara, she seems far from the flower children who, that year—the summer of love—were prophesying a future of peace and liberation and coming together. “Look at us but do not touch,” sings Nancy, crouching in the grass, “Phaedra is my name.” She is blonde and fragile and beautiful. Elsewhere in the landscape, Lee Hazlewood rides his horse along the shore. Each verse becomes unsettlingly shorter, the song progresses, but in the entire three minutes and forty seconds the two never appear in the same frame. They never come together.

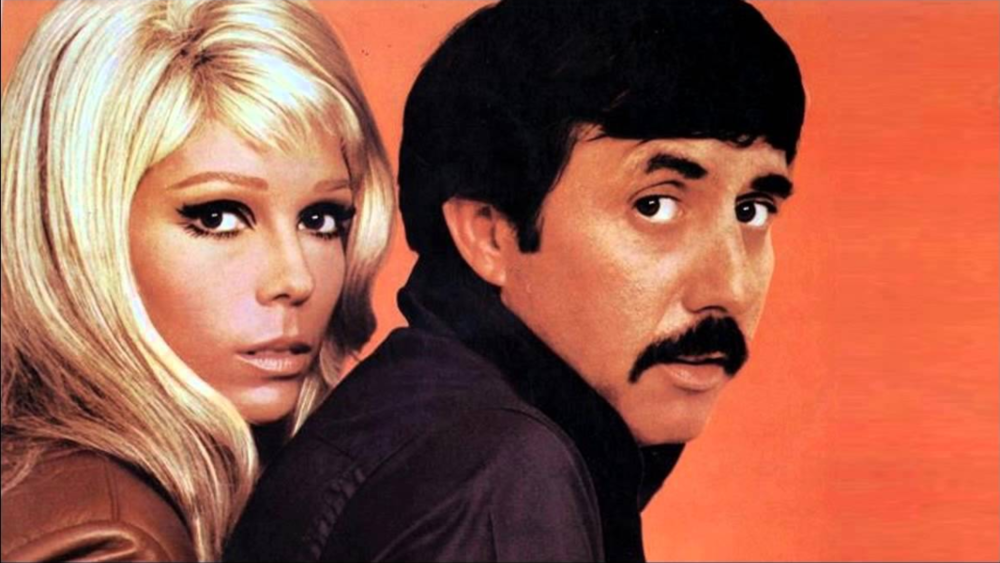

This Very Special Television Presentation of “Some Velvet Morning” is a precise encapsulation of the haunting weirdness of the song that Hazlewood wrote and recorded with Sinatra in 1967. Nancy Sinatra had, until the mid-sixties, been the favorite daughter of her famous father and a mediocre pop singer without a hit. Hazlewood changed that. He wrote “These Boots Are Made For Walking” for Nancy. He wrote “Sugar Town” for Nancy. And he wrote “Some Velvet Morning,” a song that Rolling Stone, The Daily Telegraph and other publications have called one of the greatest duets ever recorded.

1967 was the year of “Some Velvet Morning” and the horse ride along the Pacific featured in NBC’s “Moving With Nancy”, brought to you by the Royal Crown Cola Company (“It’s a mad, mad, mad! mad cola”). 1967 was also the year of the Summer of Love, the crystallization of all that the 1960s promised. Better futures were in the air. The year had begun with San Francisco’s Human Be-In, where Timothy Leary had urged the crowds to “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” Peace. Love. Come Together. That was the general idea. The San Francisco Oracle issued an announcement that summed up the project of 1967: “A new concept of celebrations beneath the human underground must emerge, become conscious, and be shared, so a revolution can be formed with a renaissance of compassion, awareness, and love, and the revelation of unity for all mankind.”

Per the Oxford English Dictionary, Compassion: Suffering together with another, participation in suffering; fellow-feeling.

“Some Velvet Morning” was recorded at Capitol Studios in the autumn of 1967. Six months earlier, Joan Didion wrote her essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.” Of that year she said, “The market was steady and the GNP high and a great many articulate people seemed to have a sense of high social purpose and it might have been a spring of brave hopes and national promise, but it was not, and more and more people had the uneasy apprehension that it was not.”

Hazlewood begins: “Some velvet morning when I’m straight, I’m gonna open up your gate.” He promises maybe to tell you about Phaedra, and “how she gave (him) life, and how she made it end.” Then the time signature changes. Hazlewood sings his part in 4/4, while Sinatra sings hers in waltz time. The strings get sickly sweet. Nancy sings about dragonflies and daffodils. Tempo shifts, and Lee sings the same thing he sung before, but faster. The music gradually accelerates, as though the vocalists are hurtling closer to one another, their parts cutting closer and closer together. The overall effect is menacing, full of sex, and to be inside the duet is to exist, for a few moments, as both predator and prey. The vocalists never sing together.

When the final frames of Lee Hazlewood galloping across the ridge and into the night fade to black, NBC brings the “Moving With Nancy” audience to Spain. On a rooftop, by a swimming pool, atop a Spanish castle, and surrounded by motionless women sipping from goblets, Robie Porter smiles and sings news of RC’s “mad, mad, mad! mad cola.” Why is Robie Porter in Spain, singing about Royal Crown Cola? It’s never quite clear. Porter was an Australian lap steel guitarist, who made a minor name for himself as Rob E.G. playing instrumental covers of popular country and western hits. In 1967 he moved to California, trying to make it big. The RC spot on “Moving With Nancy” was as big as he got, and soon after he moved back home, to Ashfield, the inner-west suburb of Sydney where I heard “Some Velvet Morning” for the first time.

But it was Rowland S. Howard’s version of “Some Velvet Morning” that I heard initially, not Hazlewood’s. Lying on my bed on a Friday night I clicked through from one YouTube clip to another. I recall that I stumbled upon the Rowland S. Howard/Lydia Lunch version of the song, put it on a loop and played it over, and over, and over again.

Rowland S. Howard’s guitar tone is raw, it is weeping, it’s vibrating like a pinched nerve. Nearly all his life Howard played harsh, biting chords on a Jaguar, with the reverb turned way up on his Fender Twin. That sound was distorted and fed back, the sonic manifestation of electricity in the wires, or the snap of a vertebra. His hand was never more than an inch away from the vibrato arm, and when you watch footage of Howard playing, he looks, often, as though he is trembling. The sound is exposed, volatile, broken-bodied. “You could tell how sensitive he was,” said Lydia Lunch, years later, “Just by the nature of the sounds he created.”

Rowland S. Howard’s version of the song seemed to model the prevailing feeling I had in that era of my life—that nothing was moving forward and nothing was moving back. The year I first heard “Some Velvet Morning” was the year of a twice-broken heart, of anaemia, of the melanoma in my grandfather’s brain, the year of the death of the last Pinta Island tortoise and the retreat of the Arctic ice-sheet, the year people died on a shipwrecked luxury cruise liner, in a midnight Batman screening, in a Connecticut elementary school, and the year that was rumored to be the last—the apocalypse was expected in December. There seemed to be a general awareness of, if not participation in suffering, but not much in the way of fellow-feeling. “Apprehension” would be an apt descriptor. Something in the air of the times menaced a future of opened gates, in the precise tone that Rowland S. Howard spat it through my laptop’s speakers. But I could not positively characterize what that open gate would look like. My present seemed to me nothing but the loose threads of anecdote observed with flickering attention, and as this interminable present extended itself I was growing only more emotional, more anxious, more inclined to fury.

Before Nancy, Lee Hazlewood was a cowboy of sorts. Born in Oklahoma to an oil wildcatter and a housewife, he grew up in Arkansas, Louisiana, and, finally, Texas. After serving in the Korean War, Hazlewood landed a job as a late-night radio DJ in Phoenix, Arizona. There, he started the label “Viv,” signing the twangy instrumentalist Duane Eddy and writing and producing tracks like “The Fool” for Sanford Clark and Al Casey’s “Surfin’ Hootenany.” In 1963, Hazlewood moved to Los Angeles and recorded his first solo record at Western Studios, Trouble Is A Lonesome Town. It was a concept album that told the stories of the residents of Trouble, hard-bitten songs laden with all the misfit character and southern gothic ennui of a Carson McCullers novel, and all the cheap sentiment of bad Hollywood Westerns. It sounded, and sounds, like nothing else.

Regardless, Trouble Is A Lonesome Town didn’t get Hazlewood very far. A few years after its release, the A&R department at Reprise asked him to work with Nancy Sinatra, who had signed to the label four years earlier, but never produced a hit. “She’d been singing up here like this,” Hazlewood told The Telegraph, “but I wanted her down here where I could hear her right. We lowered her singing about two keys. I made her sound like a tough little broad. I wanted her to sing like a 16-year-old girl who screwed truck drivers.” After the success of his first singles, which helped position Sinatra as a wholesomely seductive face of1960s youth culture, the two recorded an album of duets, Nancy & Lee, in 1967. “I liked Nancy very much,” Hazlewood would say. “She got the genes from her dad and she’s smart in business. We both thought a good way to make more money would be to write some boy-girl songs.” “Some Velvet Morning” was one such moneymaking, boy-girl song, where Nancy is cast as Phaedra, and Lee is going to tell you about her.

Phaedra is a woman who loses her reason. In Euripides’ version of the story, Aphrodite compels her to fall in love with her stepson, Hippolytus—but Hippolytus spurns her advances. When Phaedra can no longer bear the guilt and the force of her feelings, she takes her own life. Full of fury, Phaedra leaves behind a note telling her husband, Theseus, that Hippolytus, has raped her. But Hippolytus never touched her.

Theseus curses his son to death, refusing to believe in his innocence until his son lies dying in his arms. Technically murdered by his father, it is Phaedra, in the end, who is responsible for the death of Hippolytus. “What is this I’ve done? Where have I strayed from the highway of good sense?” Phaedra asks in Euripides’ play. “Cover me up. The tears are flowing, and my face is turned to shame. Having my mind straight is bitterness to my heart; yet madness is terrible.” Hippolytus and Phaedra never once appear together in the play at the same time.

In 1982, Lydia Lunch moved to London. “I had nothing to lose,” Lunch said in the 2011 documentary Autoluminescent, “So why not leave whatever it was I didn’t have behind, and go to London to pursue Rowland S. Howard?” Howard was then the guitar player for The Birthday Party. Living in England, the Melbourne band was miserable, sinking into heroin addiction, shortly to relocate to Berlin where the group would splinter, morphing into Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, while Rowland S. Howard went on to form Crime and the City Solution. But in 1982, the band were living together, with their girlfriends, in a putrid London squat where Howard was suffering from malnutrition. “One day the doorbell rings,” recalled Howard’s then-girlfriend, Genevieve McGuckin, “And it’s Lydia Lunch. She swans up the stairs and she’s all curves and sex on legs, and she actually asked me if I would go out for a while so she could talk to Rowland. And much to my continual bemusement, I actually went.”

Shortly thereafter Lunch and Howard recorded “Some Velvet Morning,” a song Lunch described as “an American classic of the weirdest order.” For years, Howard had been listening to Lee Hazlewood records and studying them. “He’s about as close as I come to having an idol,” he would later say in an interview.

“I’d been entertaining the idea of recording a version of ‘Some Velvet Morning,’” Howard explained, “But I couldn’t really think of anybody to do the female vocals until I met Lydia.” This is peculiar, given that it’s difficult to imagine Lunch and Sinatra in the same stratosphere, let alone the same song. If Nancy Sinatra was all flowers and vulnerability when she sang, “Phaedra is my name,” Lydia Lunch was velvet and screeching and jagged black bangs. She wore her damage like a glass heart pinned to her sleeve. She seethed with it.

The velvet morning that is promised in Hazlewood’s song is predicated on the male vocalist being “straight.” But straight can mean a great many things.

Straight: Not crooked, direct, undeviating, in unbroken sequence. Of a person, well-conducted, steady. Of a drug-user, high.

In his essay “Old Songs in New Skins,” Greil Marcus suggests, “One of the ways songs survive is that they mutate…. Sometimes this happens subtly, around the margins, in soundtracks or commercials. The song is moved just slightly off the map we normally use to orient ourselves—but in a way that, in a year or ten, may completely change how we hear it, what associations we bring to it. Pop songs are always talked about as the soundtrack to our lives, when all that means is that pop songs are no more than containers for nostalgia. But lives change and so do soundtracks, even if they’re made up of the same songs.”

Lives do change, and so do the songs that resonate with us, but it strikes me as strange that no matter how many versions of “Some Velvet Morning” I hear it is the oldest Hazlewood/Sinatra and Howard/Lunch versions that feel most vital to me. These products of my parents’ generation speak more to my present than the poor counterfeits of my own.

Slowdive recorded their version of “Some Velvet Morning” in 1993. But despite a well-earned reputation as one of the greatest bands to emerge out of the 90s shoegaze scene, their cover is dismal. When Neil Halstead and Rachel Goswell mutter the ever-shortening verses, the emotional complexity of Hazlewood and Howard’s versions is dimmed and distorted into a static-ridden dirge. And if Slowdive’s version sounds like the hushed-down buzz of a depressive episode, Primal Scream’s version, recorded in 2002 with Kate Moss taking the female vocals, sounds like the soundtrack to a glow stick-lit drug binge. Both covers seem to manifest a coke-fuelled neoliberal emptiness, something hopeless that began to grow like cancer in the 90s and early 2000s—an era that I could rightfully be nostalgic about. The contemporaneous versions of the “Some Velvet Morning” don’t resonate with me like the older versions do.

In a 2007 PBS documentary, Summer of Love, San Francisco music critic Joel Selvin described 1967 as a defining year. “For a minute there,” he said, “It was real. And we all knew it, and it was in our hearts and in our minds. And if we could’ve continued to act on that and grow on that, you know, who knows what happens? But we didn’t. And what’s left is like a ring around the bathtub. You know, it’s just a residue of something much greater.”

Some Velvet Morning speaks to our present because it seems to prophecy the broken promise of the future that the 1960s envisaged. There will be no coming together. The time signatures will not align. The way forward is not straight: it is crooked, indirect, deviating, occurring in broken sequence. The song models the double-bind of an era when all pasts and futures seem to circle back on themselves, a present where the words of Phaedra resound now more than ever: “Having my mind straight is bitterness to my heart; yet madness is terrible.”

“Moving With Nancy” presses on through its hour. Hazlewood and Sinatra sing a stiff rendition of “Jackson”, but Hazlewood throws the show off-kilter, somehow. You get the impression that NBC has no real use for cowboy psychedelia. The special features appearances from Dean Martin and a love bead-wearing Sammy Davis Jr, as well as a tour through the high-points of Daddy Sinatra’s illustrious career. Don’t forget for a minute that RC cola has a “mad, mad, mad! mad taste.” The climax of the hour brings us to a grand sound-stage performance of “Younger Than Springtime” by Frank. The prudent rendition of a family-friendly classic could be mistaken for old footage from Daddy’s heyday, were it not for the technicolour and the fleshiness of his jowls. Nancy looks on adoringly while he croons, with a bow in her beautiful, blonde hair. When Frank finishes, it turns out that Lee has been in the sound booth all along. His verdict on Frank’s performance: “it’s better than black eyed peas on New Years’ day.” Nancy is on the other side of the plexiglass, looking at and touching nothing but Daddy.

In a 2013 interview, Nancy Sinatra said, “I always thought that Lee was a fairy-tale writer. He wrote children’s stories, and then when he put them to music, they had a certain connotation. But then when we did them together, it became a chemical thing. It turned from a sweet little fairy tale to a sexual fantasy. And the thing was, we didn’t have a sexual relationship, Lee and I. I think a lot of the reason why we had the sound and chemistry we had on record was because we didn’t. It was implied and inferred, but it never happened.” As much as he might have wanted Nancy to sound like a 16-year-old girl who screwed truck drivers, Hazlewood never—so far as it’s known—breached that divide. There were eleven years and a war and lonesome towns and Trouble between them. “We made hit records,” Hazlewood said, “and she went home and I went home.”

Originally released as an EP, the Howard/Lunch version of “Some Velvet Morning” would later appear as a bonus track to Honeymoon In Red, an album which you might as well call a Howard/Lunch collaboration.

A teenage runaway, Lydia Lunch had come up as a part of the New York punk/no-wave scene in the 1970s. Both a musician and a performance artist, Lunch was beautiful and terrifying. Her songs were frequently concerned with power, sex and destruction, but it was never clear who was meant to occupy the position of power, nor who was the agent of destruction. Sometimes she is inciting her lover to beat a cat to death, sometimes she is describing the sexual abuse she experienced at the hands of her father. “I am not the only one living under a life sentence of willing victimhood and abuse,” Lunch would say. “With compassion and understanding, I seek to illustrate this eternal dilemma and give voice to those who like myself are forever sick with desire.”

One gets the impression that “compassion” means something different to Lydia Lunch when she speaks of abuse and desire than it did to the writers in the San Francisco Oracle in 1967.

When Hazlewood suggests that he’ll “maybe tell you about Phaedra,” he goes further. He might tell you about “how she made gave me life, and how she made it end.” We know how it ends—Phaedra cannot think straight, but she can’t bear her madness. Roland Barthes called the story of Phaedra a “nominalist tragedy.” Nominalist, because it isn’t the guilt of her obsession with Hippolytus that constitutes her problem, so much as her silence about it. The point of highest drama is when Phaedra finally puts her desire into words. This is the tragedy. It was Phaedra’s silence that kept her alive; once she’s named what she wants, her only recourse is death. What is important, for both Euripides, and for Hazlewood, is how Phaedra makes it end.

Phaedra is both predator and prey. And don’t most people feel like they have occupied both of those positions? Sometimes it is possible to be both at once. It is not necessary for the act of a vengeful God to cause a woman to lose her reason. Reason can be lost all by itself.

As a child I would sometimes spin around in circles until I fell down. I would eat until my stomach hurt, I would replay a song until the tape snapped, I would wear a dress until the seams unravelled. When I grew up I learned to drink until I blacked out, to smoke until my lungs hurt. I listened to songs just as often, but there was no longer any tape to snap.

I am rarely able to fully articulate my desires in the present moment. “You have to tell me what you want,” a man who broke my heart told me, right around the time I first heard ‘Some Velvet Morning.’ “We can’t go forward unless you tell me.” My emotional landscape hasn’t changed dramatically since that evening. But being emotional, inarticulate, and inclined to fury does not seem to me to be an inappropriate response to the present moment.

Lee Hazlewood all but disappeared after the 1970s. He hated the preening hyperbole of progressive rock, and the moneymaking boy-girl songs had made him enough, by then, to quit. Hazlewood moved to Sweden. “It was crazy,” Sinatra told the New York Times. “He really left me in the lurch. He kept shooting himself in the foot all the time, and I never knew why. He was always his own worst enemy.” Hazlewood slowly retired from music, until Thurston Moore rereleased his records in the ‘90s and Hazlewood took on a kind of cult following. Before he died in 2007, Hazlewood had chosen his own epitaph: “Didn’t he ramble.”

“Some velvet morning when I’m straight, I’m going to open up your gate,” the man in Hazlewood’s song promises. But by the end of the song it seems like he’s never going to get straight enough to make good on the promise.

Having my mind straight is bitterness to my heart; yet madness is terrible.

I have, all my life, been fascinated by the 1960s and 70s. These were the decades when my parents were children and young adults, and in their recollections of the past—free education, social democratic government, punk, surfing, glam, staying out until dark till voices called them home—their faces look haunted. Their faces suggest that today might have been different, or worse, that things really might have been better back then. That somewhere along the way a promise was broken.

Phaedra asks: “Where have I strayed from the highway of good sense?”

The answer might be found in the NBC special itself.

Because adopting the technicolor, the miniskirts, the lingo—”Groovy!”—and the love beads of an era is just a way of co-opting the signifiers of a cultural revolution and invoking the excitement of its ‘madness’ while simultaneously ringing its death knell. The hopes and dreams of the 60s are crushed just a little each time Robie Porter tells you how “mad!” Royal Crown Cola is. Lee Hazlewood appears in the middle of all this, a Trouble-bound presence out of place and time, seeming to signal that Cola is no kind of dream, but the dreams of the flower children aren’t built to last.

It seems to me that “Some Velvet Morning” is struck-through with the same uneasy apprehension Joan Didion felt during the period between the Human Be-In and the summer of love. Hazlewood promises not the peaceful revolution of the future, but its failure. As Lee sings in 4/4 and Nancy sings in 3/4 and their voices approach each other without quite touching, what “Some Velvet Morning” appears to augur is that the future of unity and love would falter, that compassion had a darker flipside, and that in the end we would find it impossible to come together.

At the end of the day she went home and he went home, nobody ever opened the gate.

Purchase a copy of the current issue of The Believer here, and subscribe today to receive the next six issues for $48.