Shanzhai (山寨) is the Chinese neologism for “fake.” There are now also expressions such as shanzhaism (山寨主義), shanzhai culture (山寨文化), and shanzhai spirit (山寨精神). Today shanzhai encompasses all areas of life in China. There are shanzhai books, a shanzhai Nobel Prize, shanzhai movies, shanzhai politicians, and shanzhai stars. Initially the term was applied to cell phones. Shanzhai cell phones are forgeries of branded products such as Nokia or Samsung. They are sold under names such as Nokir, Samsing, or Anycat. But they are actually anything but crude forgeries. In terms of design and function they are hardly inferior to the original. Technological or aesthetic modifications give them their own identity. They are multifunctional and stylish. Shanzhai products are characterized in particular by a high degree of flexibility. For example, they can adapt very quickly to particular needs and situations, which is not possible for products made by large companies because of their long production cycles. The shanzhai fully exploits the situation’s potential. For this reason alone it represents a genuinely Chinese phenomenon.

The ingenuity of shanzhai products is frequently superior to that of the original. For example, one shanzhai cell phone has the additional function of being able to identify counterfeit money. In this way it has established itself as an original. The new emerges from surprising variations and combinations. The shanzhai illustrates a particularly type of creativity. Gradually its products depart from the original, until they mutate into originals themselves. Established labels are constantly modified. Adidas becomes Adidos, Adadas, Adadis, Adis, Dasida, and so on. A truly Dadaist game is being played

Does it make the product a fake if it shows the Apple mutating into incredible shapes, people growing wings, or the Puma learning to smoke? with these labels that not only initiates creativity but also parodically or subversively affects positions of economic power and monopolies. This is a combination of subversion and creation.

The word shanzhai literally means “mountain stronghold.” The famous novel Water Margin (shui hu zhuan, 水滸傳) tells how, during the Song dynasty, outlaws (peasants, officials, merchants, fishermen, officers, and monks) would hole up in a mountain stronghold to fight the corrupt regime. The literary context itself lends shanzhai a subversive dimension. Even examples of shanzhai on the Internet that parody the Party-controlled state media are interpreted as subversive acts directed against the monopoly of opinion and representation. Inherent in this interpretation is the hope that the shanzhai movement might deconstruct the power of state authority at the political level and release democratic energies. However, if we reduce shanzhai to its anarchic and subversive aspect, we lose sight of its playful and creative potential. It is precisely the way in which it was produced and created, not its rebellious content, that aligns the novel Water Margin with shanzhai. In the first place, the authorship of the novel is very uncertain. It is presumed that the stories that form the heart of the novel were written by several authors. Moreover, there are many very different versions of the novel. One version contains seventy chapters, while others have 100 or even 120 chapters. In China, cultural products are often not attributed to any one individual. They frequently have a collective origin and do not display forms of expression associated with an individual, creative genius.

They cannot be unequivocally ascribed to one artist who would emerge as their owner or even their creator. Other classic works, too, such as Dream of the Red Chamber (hong lou meng, 紅樓夢) or Romance of the Three Kingdoms (san guo yan yi, 三國演義), have been rewritten time and again. There are different versions of them by different authors, some with and some without a happy ending.

In the Chinese literary world today we can see a similar process. If a novel is very successful, fakes immediately appear. They are not always inferior imitations that simulate a nonexistent proximity to the original. Alongside the obvious fraudulent labeling, there are also fakes that transform the original by embedding it in a new context or giving it a surprising twist. Their creativity is based on active transformation and variation. Even the success of Harry Potter initiated this dynamic. There now exist numerous Harry Potter fakes that perpetuate and transform the original. Harry Potter and the Porcelain Doll, for instance, makes the story Chinese. Together with his Chinese friends Long and Xing, Harry Potter defeats his Eastern adversary Yandomort, the Chinese equivalent of Voldemort, on the sacred mountain of Taishan. Harry Potter can speak fluent Chinese, but has trouble eating with chopsticks, and so on.

Shanzhai products do not deliberately set out to deceive. Indeed, their attraction lies in how they specifically draw attention to the fact that they are not original, that they are playing with the original. Shanzhai’s game of fakery inherently produces deconstructive energies. Shanzhai label design also exhibits humorous characteristics. On the shanzhai iPncne cell phone, the label looks like an original iPhone label that has slightly worn away. Shanzhai products often have their own charm. Their creativity, which cannot be denied, is determined not by the discontinuity and suddenness of a new creation that completely breaks with the old, but by the playful enjoyment in modifying, varying, combining, and transforming the old.

Process and change also dominate Chinese art history. Those replicas or persisting creations that constantly alter a master’s oeuvre and adapt to new circumstances are themselves nothing but superb shanzhai products. Continual transformation has established itself in China as a method of creation and creativity. The shanzhai movement deconstructs creation as creatio ex nihilo. Shanzhai is decreation. It opposes identity with transformational difference, indeed working, active differing; Being with the process; and essence with the path. In this way shanzhai manifests the genuinely Chinese spirit.

Although it has no creative genius, nature is actually more creative than the greatest human genius. Indeed, high-tech products are often shanzhai versions of products of nature. The creativity of nature itself relies on a continual process of variation, combination, and mutation. Evolution too follows the model of constant transformation and adaptation. The creativity inherent in shanzhai will elude the West if the West sees it only as deception, plagiarism, and the infringement of intellectual property.

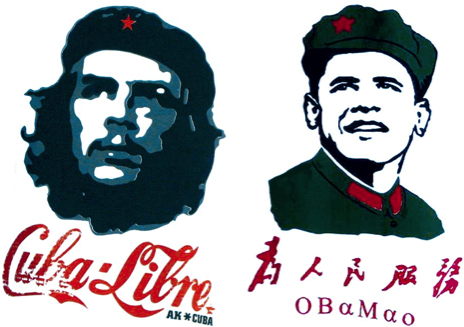

Shanzhai operates through intensive hybridization. In China, Maoism was itself a kind of shanzhai Marxism. In the absence of a working-class and industrial proletariat in China, Maoism undertook a transformation of Marx’s original doctrine. In its ability to hybridize, Chinese communism is now adapting to turbo-capitalism. The Chinese clearly see no contradiction between capitalism and Marxism. Indeed, contradiction is not a Chinese concept. Chinese thought tends more toward “both-and” than “either-or.” Evidently Chinese communism shows itself to be as capable of change as the oeuvre of a great master that is open to constant transformations. It presents itself as a hybrid body. The anti-essentialism of the Chinese thought process allows no fixed ideological definition. As a result, we might expect surprising hybrid and shanzhai forms in Chinese politics too. The political system in China today already reveals markedly hybrid characteristics. Over time Chinese shanzhai communism may mutate into a political form that one could very well call shanzhai democracy, especially since the shanzhai movement releases anti-authoritarian, subversive energies.

This is an excerpt from Byung-Chul Han’s Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese, available from the MIT Press.

Purchase a copy of the current issue of The Believer here, and subscribe today to receive the next six issues for $48.