In late March of 1997, while working as a receptionist at an alternative newspaper in Manhattan, I was asked to sign for a package from Henry Holt & Co. The package looked like most any other review copy from a publisher, but thicker than most, and heavier, and that made me curious. It was addressed to one of the editors, but I nevertheless opened one end of the mailer and slipped out the cover letter.

“Dear Editor/Reviewer,” it began.“The wait is finally over. Enclosed please find your advance reading copy of Thomas Pynchon’s latest novel, Mason & Dixon.” Something deep inside me began to tingle, then went numb. “You are among a select group of editors and reviewers who are receiving an advance copy of Mason & Dixon. Because of the limited number available, this is the only copy that will be sent to your office. Please keep an eye on it.” I opened my bag and slipped the massive novel inside. The editor would never miss it.

When I crawled into bed in my tiny Brooklyn apartment that night, I brought the book with me, propped myself up on the pillows, and began reading with the 800-page volume balanced on my chest. It took me a few pages to adjust to the eighteenth-century typography and spelling, but once I clicked into it, it became obvious I was reading something remarkable. I thought Mason & Dixon was a profound and hilarious masterpiece, and quite possibly the greatest thing he’d ever written. But as the evenings passed and I got deeper into the novel, I noticed it was taking me longer to focus on each page, and I was losing my place more often.

By page 300, the print seemed to be shrinking out of view, so I started bringing a magnifying glass to bed with me. By page 500, I knew I had to reluctantly abandon the idea of reading in bed, moving the operation to the kitchen table. There under the intense direct light of the table lamp, I could crouch an inch above the page, magnifier in hand, scraping across each line.

With sixty pages to go, I had to give up. I had no choice. My eyes were simply no longer capable of working with reflected light on paper. Over the three weeks I’d been reading the book, they’d crashed on me for good.

I can’t say I was terribly surprised in 1989 when the doctors told me I was going blind. The evidence had been there for a long time. It wasn’t until I was in my mid-twenties that it was finally given a technical name: retinitis pigmentosa, a genetically-linked degenerative eye disease, the collective symptoms of which eventually result in total blindness. In most cases, the symptoms don’t start making themselves obvious until age sixty or later, but I was one of those early bloomers.

Yet while I had all the classic symptoms before I hit my teens, I could work around them and ignore the larger picture. For a long time I went about my business as if nothing was wrong. Then along came Mason & Dixon, the novel it seemed I had been waiting my whole life to read. I was frustrated and more than a little pissed—having come that far and gotten so close, I needed to know how it ended. Then I had an idea.

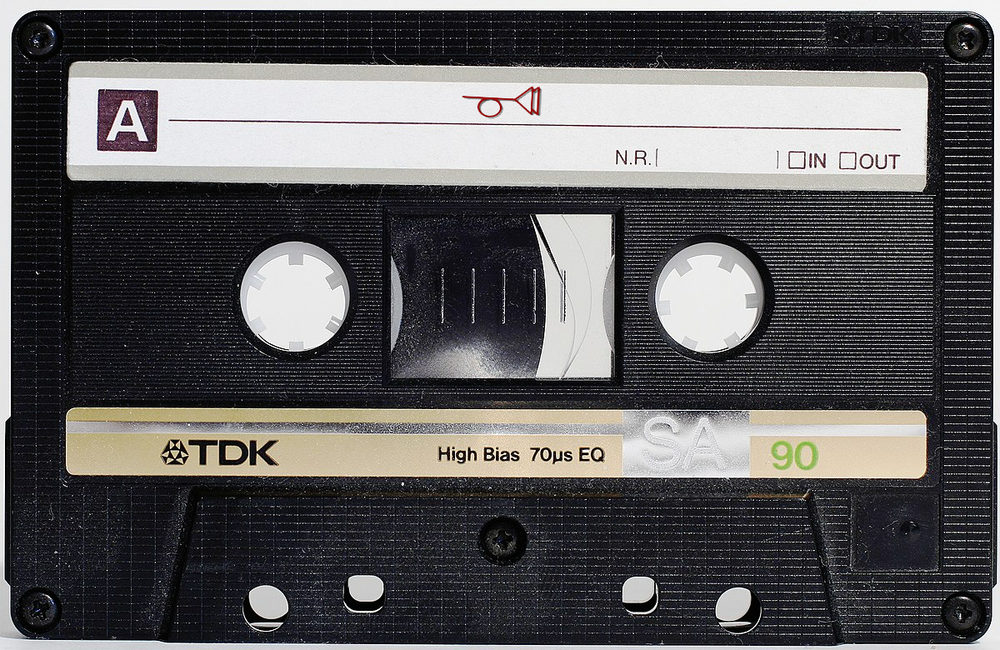

I’d owned a few audiobooks in the past, but I never really took them seriously. I listened to them the same way I would, say, a Mercury Theater production of “The Secret Sharer.” Entertaining as they might be, audiobooks never struck me as a valid way to approach literature. Part of that may be because literature was so hard to find on audio in the eighties and nineties. Apart from Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and Dickens, most audiobooks came straight off the bestseller lists. Their publication by major houses was an economic decision, meaning most commercially available audiobooks were self-help, business books, celebrity tell-alls, or novels by Stephen King and John Grisham. And as if to add insult to, well, insult, most were heavily, often clumsily edited in order to fit a 300 page book onto a conveniently-packaged four cassettes.

There was, yes, Books for the Blind, a program through the Library of Congress which started in 1931. I could call Books for the Blind and request Journey to the End of the Night, 120 Days of Sodom, or any book I wanted, someone would record it, and I would be sent the result on a set of specially-designed four-track cassettes which could only be played on a specially-designed tape player. I would have the tapes for a month, then have to send them back to become part of the LoC’s permanent collection. But for the simple sake of convenience, and tapes I could keep and play on any tape player, I was pretty much stuck with crap.

When I started looking around online, I was amazed to discover Books on Tape had released an unabridged audio edition of Mason & Dixon. That old tingle returned. I’d be able to hear those last sixty pages. Better still, I’d be able to read the whole thing again, in a way.

Ten days later the tapes arrived in two large plastic cases. I set up a cassette player that night on the scarred, rickety nightstand and inserted the first of twenty cassettes read by Jonathan Reese.

Mr. Pynchon’s novels present any number of challenges to a would-be audio narrator that go far beyond simple questions of stamina. Not only does he juggle a huge array of characters, but he also sprinkles his prose with foreign names and phrases, scientific terminology, complex puns and more troubling still, all those little songs scattered throughout. An actor could have a field day, but Mr. Reese stepped back and simply read the words. It’s always the words, really, that are the most important thing. It was the best decision he could’ve made. This wasn’t a radio play, after all. Not to me it wasn’t. It was a necessity, and Reese did a brilliant job, denoting different characters with only the slightest vocal variation and reading the songs like short rhythmic poems. In time, he vanished completely behind the prose.

I can’t say the book didn’t lose something in the translation from print to audio. Part of the experience of reading Mason & Dixon was the typography, which of course can’t easily be read aloud. While I may never know now if I have lost anything similar from other books I’ve listened to since, in this instance at least I knew it was there on the page, and as I listened, could hear it beneath the words he was speaking. It’s not the same experience, no. It’s not like holding a book and turning pages and hearing the character voices you choose in your imagination. There’s no way to mark favorite passages, and even the unique smell of a book is gone. But at present, it’s the closest I can come to reading.

After finishing the last tape and at long last hearing how the book ended, the question immediately became, “What do I do now?” I looked, and none of Mr. Pynchon’s other novels were available on audio.

It would be nearly a decade before Pynchon’s next novel, Against the Day, was released in 2006. In those intervening years, the audiobook industry grew considerably. More major publishing houses, and more independent audiobook companies like Caedmon and Tantor, began diving into the game. Publishers began reaching back into their catalogs to produce audiobooks of more fundamental literary titles. Also, in switching standard format from audio cassette to compact disc, unabridged versions became the norm. Suddenly you could find audios of Hemingway, Joyce, Vonnegut, Milton, Dante, Dostoevsky and Kerouac. On the downside, although there were a number of excellent professional audiobook narrators on the market, people like Frank Muller and George Guidall, publishers began to hire celebrities and television actors to narrate books. Celebrities don’t often read very well, and actors can feel compelled to act. This is how, for instance, I found myself listening to an outrageously drunk David Carradine attempting to read On the Road. It also might help explain why some bright boy of an audio producer thought it would be a good idea to have a British soap actor narrate Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer.

Mr. Pynchon’s novels collectively remain a unique animal in how they necessitate a certain type of reading. Not only do you need a narrator with the stamina to carry a reader for 600 pages or more, you need one who understands what he’s reading to some degree, who can capture the singular spirit and rhythm of the prose.

Recorded Books hired Claudia Howard in 1984 to build and operate the company’s first New York recording studio. She soon went on to become Recorded Books’ executive producer, a position she held for over three decades.

“It was early in the life of the industry,” Howard says. “We were one of only two small companies publishing audiobooks. We were both direct mail renters of books on cassettes, and Recorded Books had about fifty titles in the catalog. The founders thought it was time to move recording to NYC, even though the company was based in Maryland, in order to have proximity to the best stage acting community in the world. The skills of a fine narrator are usually developed through training and experience of work on stage, and the best audiobook narrators are professional actors. Casting an audiobook also has a direct correspondence to the theatrical world, as choosing the right narrator for a book is just like choosing the right actor for a part in a play or a movie. Developing a strong company of performers is all-important. Every book has a singular ‘voice,’ a point of view, a personality, no matter whether it’s in the first-person or the third-person. Over the years, producers learn the skills and talents of the actors they hire, such as abilities to play characters, do accents, do comedy, speak foreign languages—and all of these things add up to the actor’s ‘voice.’ The goal is to match a performer to a book in an inspired way.”

While the fifty book catalog consisted of works by Jack London, Robert Louis Stevenson, and other classic literature in the public domain, Recorded Books soon expanded, releasing unabridged versions of more contemporary titles. In 2005, Howard produced an audio version of Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. Which raises the question of how one goes about casting an actor to read Pynchon aloud.

“So what is the personality, the voice, speaking to us in The Crying of Lot 49?” She asks. “Published in 1966, when the author was in his late twenties, the setting is California in the early Sixties, with references to McCarthyism, the Civil Rights movement, the John Birch society, and life on the Berkeley campus. Pynchon writes the book in the third person, but we recognize we are in the mind of a cynical deep-thinker with a wry sense of humor who doesn’t seem to approve very much of the world as he sees it. The voice is very deadpan. No matter how crazy the events he describes, he’s always above it all. This is what led me to George Wilson, an actor I had worked with many times. In the past, I’d cast George in the novels of Carl Hiassen, another master of elegant farce, as well as Tom Perrotta’s Little Children, Joe Haldeman’s Forever War, and even Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, all of which are told by sly observers with a sneaky sense of humor. I felt he made the right connections.”

Having gone back again recently to take another listen to Lot 49, I noted that Wilson did a masterful job with the material. He clearly understood the mindset and the humor, and deftly captured the rhythm of the prose. As with Reese, he soon vanished beneath the text.

But as with Mason & Dixon’s eighteenth-century typography, The Crying of Lot 49 does present the narrator with one typically Pynchonian bugaboo. Namely, how do you convey the recurring Tristero icon of a muted post horn, which Oedipa Maas finds scrawled on walls all over Southern California? In Wilson’s case, after the initial description of the symbol in the text, each subsequent appearance is denoted on the audio by a moment of silence.

“One of the great things about encountering a book in audio format is you get lots of pluses—like character voices, foreign accents, proper pronunciations, regional speech, and sometimes music,” says Howard. “But when written novels contain graphic elements, or, say, footnotes, or illustrations, an audiobook publisher has a more complex job of turning it into an ears-only experience. Our guiding philosophy is always to serve the storyline, and to make sure the author’s intension is illuminated while his or her vision remains honored. With The Crying of Lot 49, the Tristero symbol is introduced graphically, but becomes quickly described in words. It is a drawing described in the text as containing ‘a loop, triangle, and trapezoid.’ After that it is always described in some way, as ‘the symbol,’ or the ‘post horn.’ So though the listener has had to imagine on their own what the symbol looks like, every time it appears, they do know what it is. Here was an instance where we were able to not make any new additions to the text, and yet feel quite confident the reader would follow what was happening on the page.”

Even more than the Tristero icon, the songs Pynchon has peppered throughout his novels from the beginning have proven to be a stumbling block when it comes to the audio editions. Like Reese, Wilson read the songs in Lot 49 like small poems, which is how Mr. Pynchon, as he’s expressed through his agent, clearly wants it. The tunes exist in his head and his head alone, so no one else should try and guess how they go. According to Howard, while she prefers to use real music when songs are included with the text, ultimately the final decision rests with the author or the author’s estate.

Sometimes, however, it seems that’s not enough. In 2007, when Tantor brought in narrator Dick Hill to read the fifty-four hour audio edition of Pynchon’s sprawling turn-of-the century novel Against the Day, Hill not only sang the songs, but was given credit on the recording as the composer.

Howard again returned to Pynchon in 2009, to produce the audio version of Inherent Vice, a work written some forty years after The Crying of Lot 49.

“Inherent Vice is a different Pynchon,” she says. “Looser, wackier, unconstrained in his imagination. The setting is again California, but this time the early 1970s, an age with a different temperament, and the characters are voices from the counterculture—drug dealers, potheads, surfers and crooks. To me, the book was also prodigiously funny, so I wanted a performer with a great sense of comedy and a wild imagination. Ron McLarty and I had recently recorded Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas together. He is a novelist in his own right, and his voice as an author mirrors his personality—boisterous, darkly witty, and wonderfully daft. He had personally lived the era, and understood the point of view.”

Here perhaps more than in any of his other novels, the music plays a key role, and Hill’s Against the Day gaffe was not forgotten. “Pynchon put more than half a dozen songs into Inherent Vice, and all were of his own creation,” Howard says. “Most likely they were written as sets of lyrics that never had a tune (though maybe, now that all books get an audio edition, authors will start to provide us with melodies). With a fictional song, we audiobook producers will sometimes find a musician to write us a melody, if we feel we can do justice to the moment in the book. The greatest example of this for me is the Recorded Books edition of The Lord of the Rings, for which we wrote thirty-five songs to be sung, variously, by Hobbits, Elves, Dwarves and men. Inherent Vice would have been that kind of challenge, for among the songs Pynchon brought into the storyline were ‘Soul Gidget’ which he described as ‘one of the few known attempts at black surf music,’ something vaguely Beach Boys, a song by a band called Spotted Dick, a ‘semi-bossa nova’ called ‘Just the Lasagna’ (sung by Carmine and the Cal-Zones, a country swing tune, ‘Repossess Man’ by Droolin’ Floyd Womack, and a ballad à la Sinatra. Only Pynchon himself could have made the attempt. Some things Pynchon are best left to the imagination.”

One of the most interesting figures within the fairly cloistered world of Pynchon audiobooks is narrator George Guidall. Originally (and still) a stage actor, Guidall narrated his first audiobook in the early Seventies, and went on to become one of the most prominent and in-demand performers in the industry. Over his long career he has narrated over 1,400 books, from Don Quixote and Crime and Punishment to Philip Roth’s The Counterlife and several bestselling legal thrillers. Along the way he also found himself in the unique position of having recorded Gravity’s Rainbow twice.

“It’s really a work of art, if it’s done right,” Guidall says of audiobook narration in general. “It’s a vocal portrait instead of a painted one. It satisfies that primal need to be told a story.”

Good narrators can also help interpret those stories for listeners, in some cases making seemingly insurmountable works much more accessible. “Gravity’s Rainbow is a prime example, says Guidall. “And so is Quixote and Marcel Proust and Dostoevsky. That’s unavoidable if the narrator knows what he’s doing. Because you’re interpreting something, not just reading it aloud. As an actor one of the best things I’ve heard from a playwright is ‘Y’know George, I’ve never heard that scene done like that before.’ That’s what it’s all about—finding new depths. I tried to read Quixote three times but could never get through it. But when it comes to performing it, you actually step into those shoes and you see the brilliance of it.”

As he puts it in an essay which appears on his website, Guidall considers himself a hermit crab, scuttling along through the bottom currents of literature and finding himself a home in someone else’s imagined truth.

Guidall narrated Gravity’s Rainbow for the first time in 1986, though who commissioned the now-impossible-to-find recording is the object of some debate. Guidall himself believes he did it for Recorded books, but he’s not absolutely certain. Others claim it was produced by Random House, though that would have been pretty early in the game for them. The copy I obtained some years back was bootlegged from a non-commercial recording made (according to the end credits) for the American Foundation of the Blind, as part of the Library of Congress’ Books for the Blind program. Whatever the case, my rough pirated copy (digitized from a set of aging and deteriorating cassettes) still reveals, beneath the drop outs and warpage, the muffled sound and hissing, a performance that is sharp and lively and insightful, and certainly on a par with what Reese had done with Mason & Dixon.

“I must tell you,” Guidall admits today. “I had no idea what I was reading. I had no idea what the book was. I’m not an intellectual. I’m an actor. And my job is to read words like I just invented them. I’m an actor and interpreter and performer. So I performed it on the most superficial level I could find. At that point no one had told me about [Steven Weisenburger’s A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion], so I just read it. I played the emotional value of the moment. I intuited his mania and his anger, his sardonic viewpoint, and thought, ‘Okay, I can do this.’ So I just went through it. When we started the second one, I listened to part of the first cassette and couldn’t listen to it anymore. It was awful.”

Guidall seemed genuinely amazed not only that I’d gotten my hands on a copy of that 1986 recording, but that I thought he gave an excellent performance.

“The first time I was just flying by the seat of my pants,” he says. “It’s interesting you should say it works, because basically the end result of an audiobook is important because it gives the reader an emotional immediacy. It’s as if it’s happening right then. It’s not a question of exposition. It’s character. It’s the fact something is happening. If it’s a rainy day, and a character is experiencing a rainy day. As an actor I just went with what I felt was the valid emotional level to play. So it was very instinctive, and if it worked for you, then I’m pleased as hell.”

In 2015, nearly three decades after that first recording, Penguin decided an official commercially-released Gravity’s Rainbow audio edition was long overdue. The popularity of audiobooks had skyrocketed thanks to Audible, and there was a huge demand for such a fundamental work of American literature. Guidall, given his well-earned reputation, as well as his familiarity with the novel, was again hired as narrator.

As he stepped into the recording booth with the novel for the second time, I asked what had changed in his approach to the work. In those intervening decades, after all, he’d narrated over a thousand other titles.

“Everything had changed by the time we got back to it,” Guidall says. “The most important thing is that I got older, and I had gravitated toward Pynchon’s state of mind as we progressed through Korea and Vietnam and Nixon and everything else the country went through. As I went through the second one I began to understand just how crazy he was on account of what he envisioned. And my God, look where we are now. Two madmen saying, ‘Mine is bigger than yours,’ and you and I are in jeopardy because of it. Plus I had Weisenburger’s guide right next to me as I was doing it, so I knew exactly what Pynchon was aiming at, which made it easier for me to read. It was a long, painstaking operation. I did it with a guy named John McElroy. He’s one of the best producers in the audiobook world, and I love working with him. He’s an amazingly intellectual guy. He knew all about it, and we discussed it a lot. A lot of talk went into it, and I was much happier with this one than I was with the first.”

Although the New York Times erroneously claimed the new edition was simply a re-release of that 1986 recording (later retracted), they lauded Guidall’s performance. He was surprised and humbled by that.

“This book’s history is incredible!” Guidall says. “There’s a lot in him that I can certainly identify with. That mixture of insane absurdity and sincere depression. It’s an amazing piece of writing—it just bowls you over. It’s about everything. I’m very happy about it, and I’m glad it’s out there.”

At present, only two of Mr. Pynchon’s novels—his 1961 debut V. and 1990’s Vineland—have yet to be adapted into audiobooks, and the original Jonathan Reese recording of Mason & Dixon has been out of print for nearly twenty years.

“Recording Pynchon requires a performer with a literary bent,” says Claudia Howard. “Embracing the work you are trying to bring alive is vital, and I think George, Ron, and George Guidall took this obligation quite seriously. They worked with a director in the studio, and it took all the brain power of both parties, narrator and director, to wend their way through the convoluted plots and the historical references and the sticky puns. Both narrator and director will pause the recording process to debate a point, or craft a better take, or simply take another shot at a challenging sentence. Pynchon is known for the sheer size and complexity of his ideas, so encountering his books in their audio editions can make the job of tackling him easier. The hard work of presenting the ideas was done in the studio, and in the hands of a fine performer, the words should flow fluently to your brain. Make of them what you will!”