Before the coronavirus, 25 percent of adjunct professors were dependent on federal assistance, according to a new study from American Federation of Teachers. A third earned less than $25,000 a year, below federal poverty standards, and tended to make between $2,000 and $7,000 a class.

Now many of them are being cut off from even this precarious existence, having courses cancelled. Some are being laid off altogether. This is unsurprising as one out of four Americans say someone in their household has lost their job. But for adjuncts it makes a delicate existence even more fragile as many now have little to fall back on in the first place.

In better times, permanent teaching gigs were thin on the ground. Even then, administrators took advantage of the glut of qualified professors to swap adjuncts out for other classes when it suited them, and usually to pay them little, especially at colleges outside of America’s big cities.

Now, adjunct professors, most with no health benefits or job security fear a new level of vulnerability. Will universities and colleges drop classes, putting adjuncts out of work? Will they bulk up on cheap adjunct labor in on line courses? Some among the army of adjuncts discuss their current and future fates below.

—Olivia Schanzer

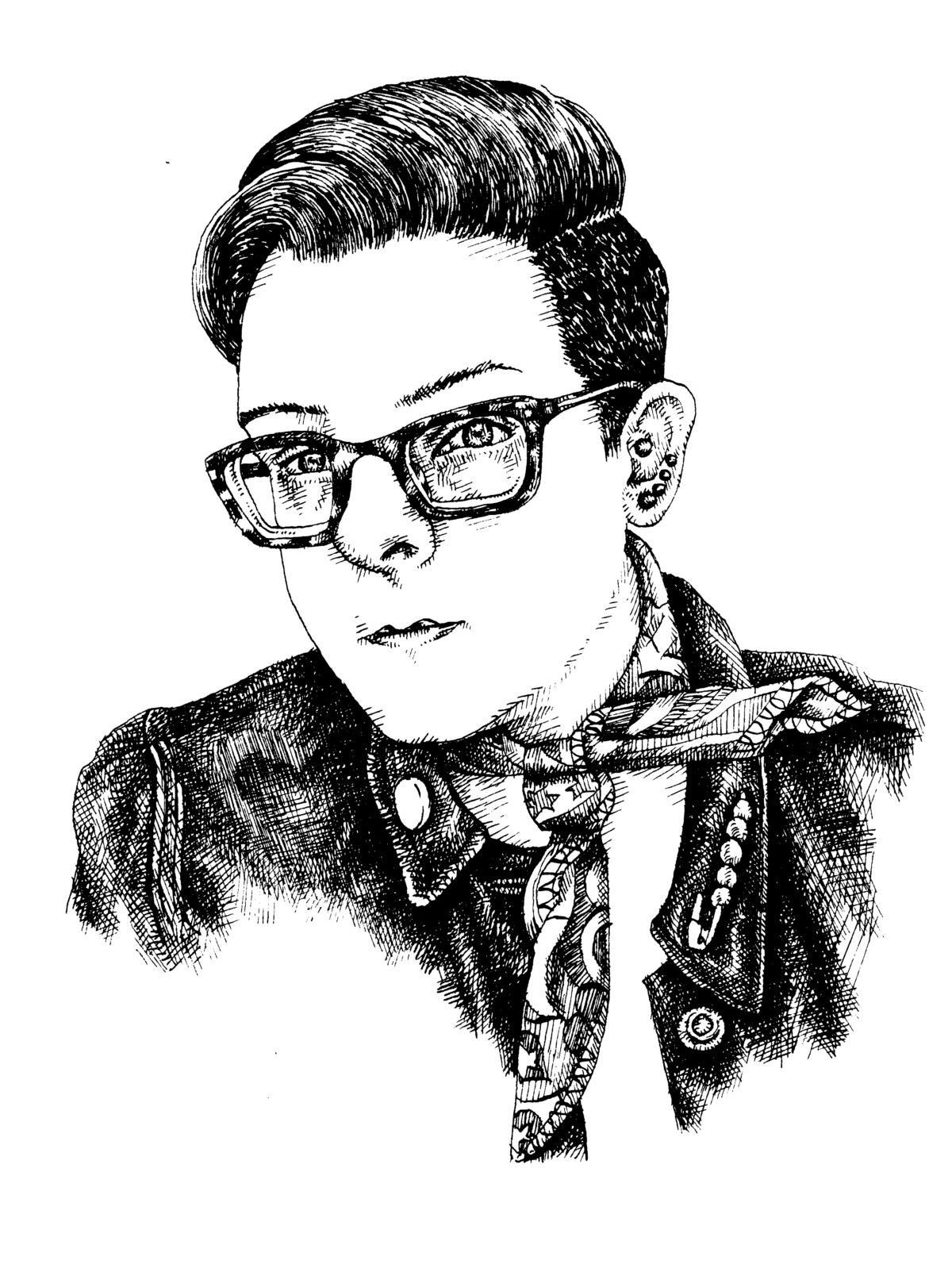

Jax Kinniburgh

Cincinnati, Ohio

25

Composition

When the pandemic hit, Jax was laid off from their adjuncting job at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. They gave the boot to a third of their teaching staff, says Jax, meaning all of their adjuncts and contingent faculty, with an abrupt note saying they would not be able to hire them and thanking them for their service.

Even before COVID, Jax was not a stranger to financial difficulty. A year ago Jax was homeless.

“I have no idea what I’m going to do now,” they say. ”I live pay check to pay check anyway.”

The amount they’d been making, $22,000 a year, $18,000 after taxes “even with working as a writing tutor” did not insulate them from the shocks of ordinary life, let alone a pandemic, and has not allowed them to develop any cushion. The University of Cincinnati, their remaining school, has promised them a summer course, “but it won’t be enough to cover rent at all.”

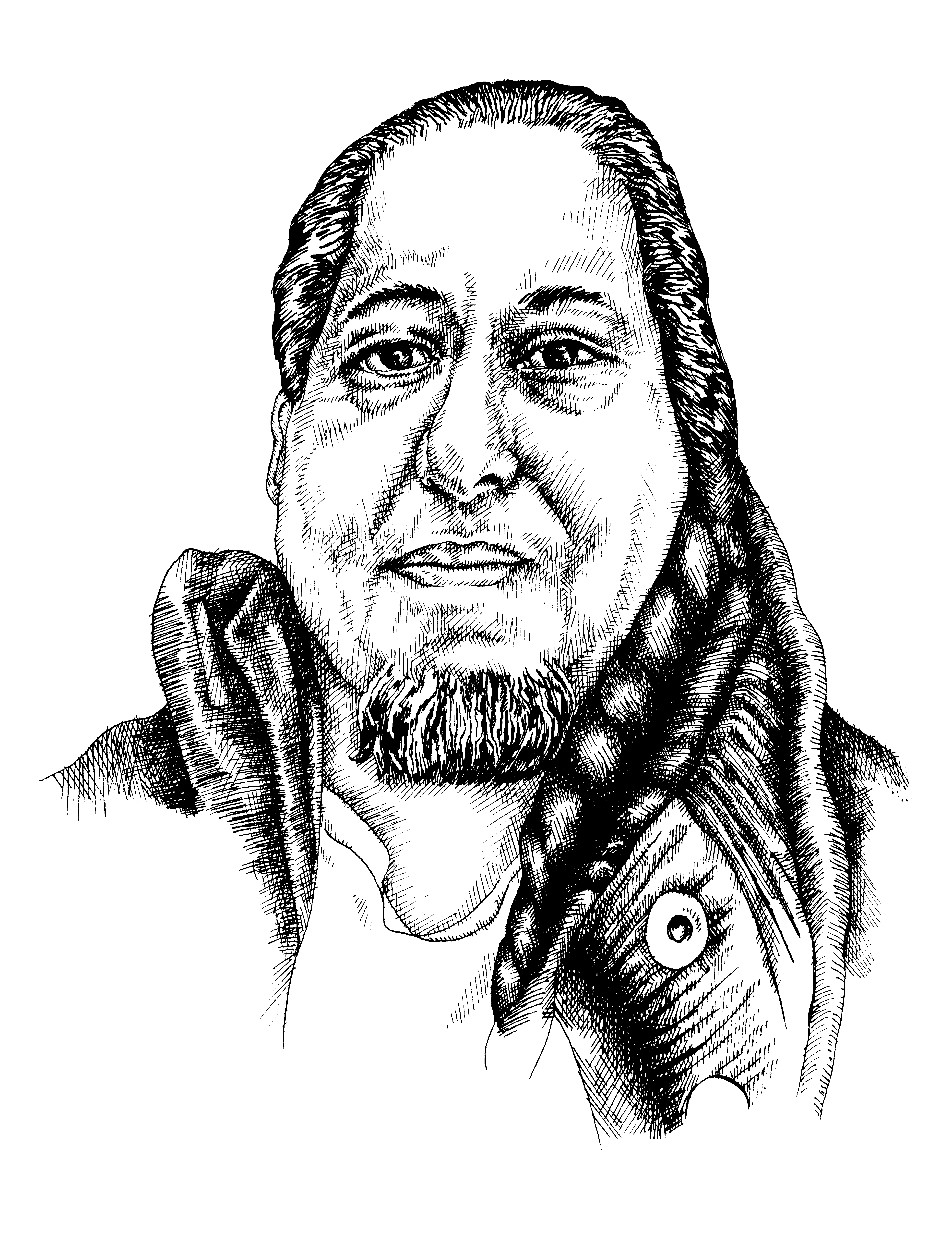

Scott Alves Barton

New York, New York

61

Food Studies

Scott is a former chef. Now, having obtained a PhD, he teaches at five different universities in New York and New Jersey including NYU and Montclair State University and Queens College. Without a car, even before Covid Scott’s commute was time-consuming and complex, sometimes taking hours.

Scott doesn’t have health insurance right now. “The four or five classes allow me to lead a modest life.” Scott makes between $40,000 and $50,000 in costly New York City.

Scott’s future is now unclear. If his summer school class isn’t cancelled– a big “if”– he’ll only be paid by the college until July 4th. He’ll pay the rent for April and probably May, “but things are going to get tricky,” he says. “I could become a statistic if the wrong things fell into place.”

Cindy Zimmerman

San Diego, California

70

Art

Cindy has adjuncted for twenty years and just retired, partially due, she says to course scarcity. “Scarcity” as she says, means “getting my classes taken away at the last minute by a full-time faculty member whose classes didn’t fill.”

At the peak of her adjuncting, Cindy would drive all over San Diego County, from the US-Mexico border to Oceanside, to teach in college from Southwestern Community College in Chula Vista to MiraCosta. She only made about $44,000 a year for the many classes she taught per semester. But she taught art to underprivileged students, she says, because she wanted to reach “populations that may not have access to the palaces of art.”

In the pandemic, she has only her art to fall back on.

Marty Baldwin

Alton, Illinois

33

English

Before Covid-19, Martha “Marty” Baldwin, commuted ten hours a week to Jefferson College in Missouri to teach English Composition. Marty made a little under $2,000 a class, while at SIUE she made $3,000. Tutoring provided an extra $480 a month. She made about $14,600 a year, qualifying for food stamps, though only $32 a month for herself and her daughter. Now much of this is probably dried up.

She lives with her parents, so that her mom can help with child care as her daughter has a rare genetic disorder, and needs help with “all her activities of daily living.”

Of the new normal after the pandemic, Marty says, “It’s strange. I’ve been in such a precarious financial position but now everybody is.”

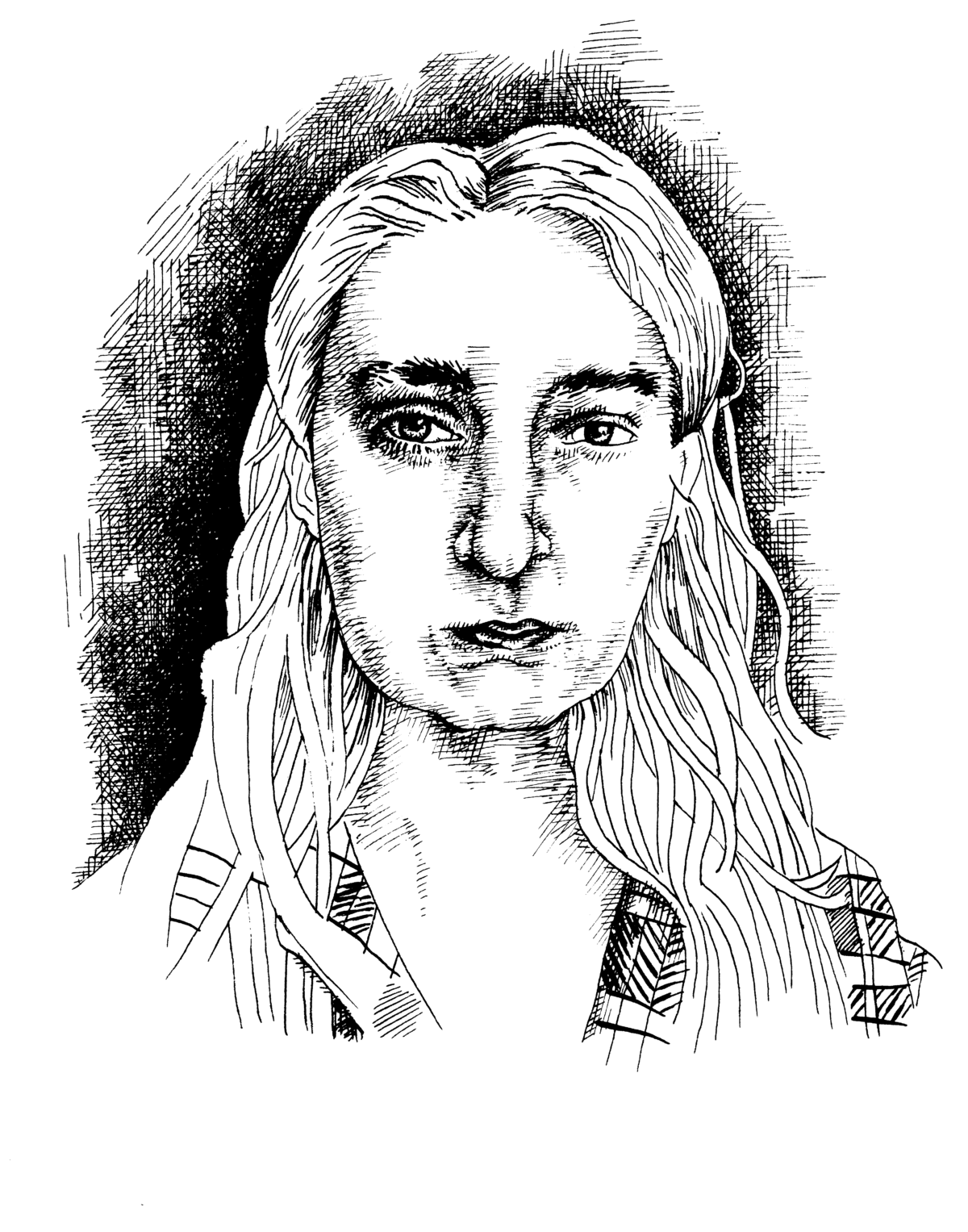

Jessee Rose Crane

New Douglas, Illinois

34

Art

In addition to adjuncting, Jessee runs an artist residency called “Rose Raft” with her husband. She is an artist, musician, teacher, and overall artistic facilitator: “I’ve, for better or worse, convinced several people to quit coffee shop jobs to go on tour,” she says.

Jessee has taught art since college at the Art Institute of Chicago, and found herself bumped from the roster at SIUE for the spring semester, where she made $250 every two weeks for 20 hours of work. As Jessee put it: “I’ve got my toe in all these things, and I’m applying for all these different positions and I don’t get anything, and so this [adjuncting] is very feast or famine.”

As she says, “I’m hoping to make it through this crisis and be able to offer educational workshops through [Rose Raft]. I was saying to my husband last night, [If I’m not rehired to teach] I might have to get a job at a grocery store.”

This piece was supported by the journalism non-profit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.