“I’m of the opinion that if it doesn’t feel bad then you don’t care enough.”

Poems can:

Hold all the shadows

Be about a flower

Communicate what’s at stake

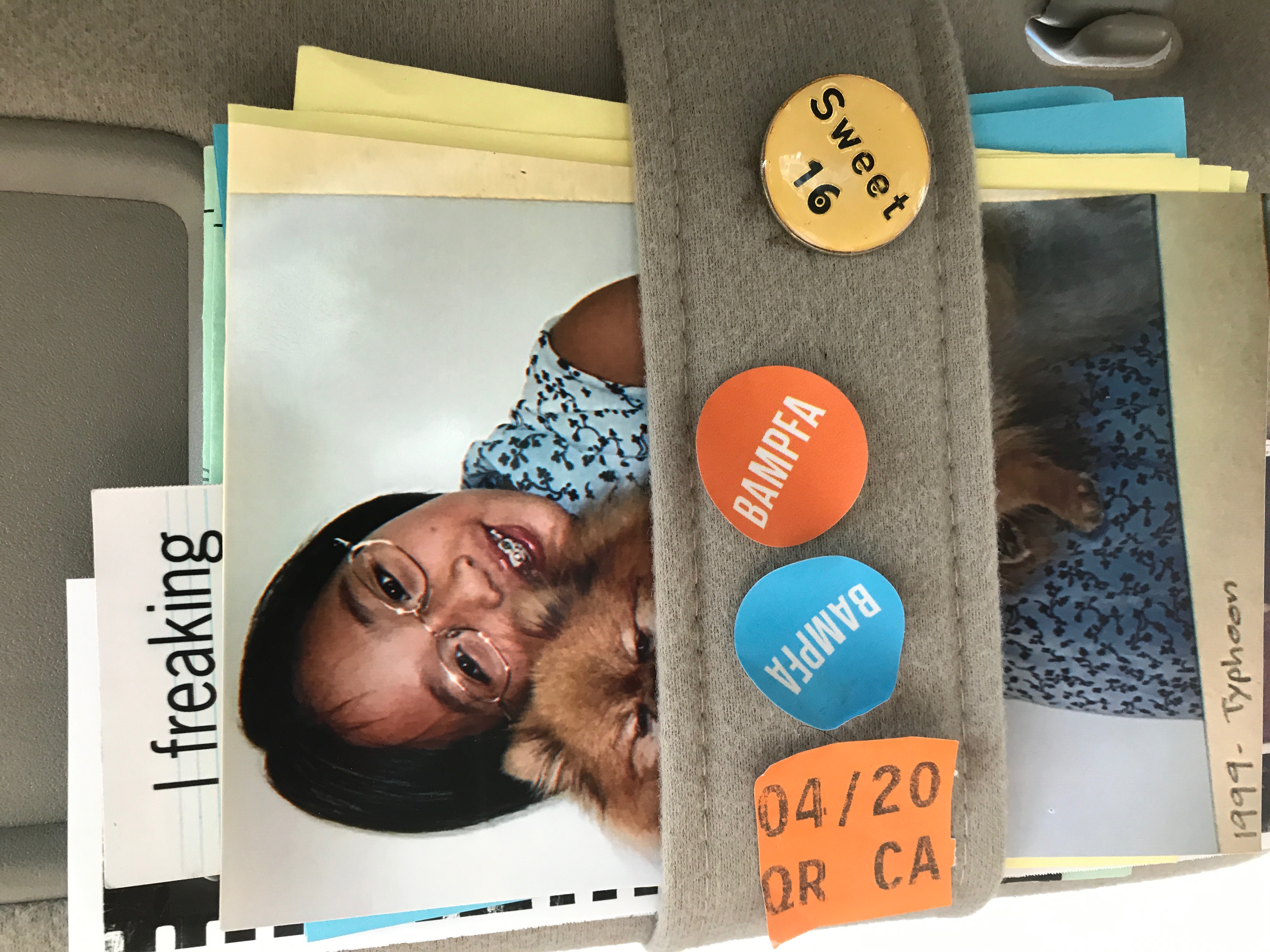

When we first met at a conference in Oakland, Trisha Low was showing a poet how to shibari tie his girlfriend. After demonstrating a chest harness tie, Trisha pushed a grocery bag of extra rope into their hands. The gesture looked how it looks when someone insists you take home extra food after they’ve made you dinner.

Trisha’s first book, The Compleat Purge, is hard to digest—it’s a suicide note epistolary that includes Last Will and Testaments and letters to various loved ones. Five years later and her new book Socialist Realism looks uncharacteristically reader friendly. It might even be called a memoir, which I suspect Trisha would hate, not because she hates memoirs but because the book is weirder than that. In Socialist Realism we’re with Trisha riding shotgun in her lover’s car, in church with her mom in Singapore, at a May Day protest, at a house show in Philly, in London visiting Freud’s old office, among other places and times. Most of all we’re with Trisha while she obsesses over what comes next, considering utopias and collective futures, the “just-not-this, or literally-anything-else.”

—Claire Grossman

CLAIRE GROSSMAN: One of the first times you read from this book, Socialist Realism, you told me you were “reading straight,” meaning (I think) that there was no fake blood involved in your performance and that what you were reading might even be mistaken for “nonfiction prose” or a “personal essay.” What changed between your first book and this one?

TRISHA LOW: So many things changed! I met you, for one, I moved to the Gay Bay Area. I am no longer obsessed with innovating methods of my own self-destruction. I don’t know—in some ways, everything changed. The aggressive performances I was giving from The Compleat Purge had started to feel routine rather than risky. With my last book I wanted to confront audiences with bluntly wasteful affect, to expose the violent truth at the heart of a cliché. But once something gets too practiced and well calibrated it doesn’t have the same raw force. I wanted to write something next that felt radically different—where the core of what I’m interested in—our performances of ourselves in the social world, identity-related friction etc.—was still intact, but where on the surface it looked almost contradictory to what I had done before. If there’s anything musicians like Bowie have taught us, it’s that there are many ways to be experimental; some are...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in