[M]y Iris kept working on a detective novel in two, three, four successive versions, in which the plot, the people, the setting, everything kept changing in bewildering bursts of frantic deletions—everything except the names (none of which I remember)…. All the odd girl could ever visualize, with startling lucidity, was the crimson cover of the final, ideal paperback on which the villain’s hairy fist would be shown pointing a pistol-shaped cigarette lighter at the reader—who was not supposed to guess until everybody in the book had died that it was, in fact, a pistol.

—Vladimir Nabokov, Look at the Harlequins!

Anything can be turned into a weapon—a handful of sand knotted in a stocking can bludgeon a person, and a wisp of air, as a bubble in a hypodermic needle, kills the patient without arousing suspicion; that we know from mystery novels. Nothing is too trivial to become a deadly riddle; generations of readers have learned that a tiny bit of water can kill a person without leaving a trace—if you put an icicle in a thermos flask and take it into the Turkish baths (Edgar Jepson and Robert Eustace, “The Tea Leaf ”). That is the hallmark of our private, artisanal infatuation with death. Nothing is too trivial. And so the detective in mystery novels is classically seen huddled over barely perceptible details, and the forensic pathologist, the detective’s most powerful current incarnation, searches for tiny perforations and microscopic lesions. At the opposite end of the spectrum is a criminal, indeed military force with a virtually infinite reach: nothing is too big for a murderous plan. The extent to which trashy films merge with military strategy is seen in the way Star Wars has colored our language. The military sphere, more than any other, is governed by breathless innovation that seizes on every detail: an endless sequence of inventions. The historical inability to stop for a moment and ask whether a new invention is actually necessary most easily finds its alibi in the military: everything that is possible must be developed, otherwise we’ll be defenseless (because it is possible).

This inability to ignore novelties goes hand in hand with the fear of failing to grasp the significance of a crucial technological advance. It inspires stories that reflect the fairy-tale trope of scornfully rejecting a magical object out of ignorance. One classic anecdote is related by Baron Hermann von Eckardtstein (Lebenserinnerungen und politische Denkwürdigkeiten, 1919). According to the author, Bismarck once spoke of himself as lacking any feel for technology whatsoever; to bolster his—possibly correct—view that in a statesman this could not be seen as a shortcoming, he claimed that Friedrich II and Napoleon had lacked this feel as well. And then Bismarck gave the following example: Once, at Johannisburg Palace, Prince Metternich had told him how he was called to Napoleon, then residing in Vienna’s Hofburg, shortly after the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805. “Suddenly, he said, the door of Napoleon’s study opened, a young man virtually came flying out, and Napoleon hurled the coarsest curses after him.Then he told Metternich in a tone of utter indignation that Livingston, the American ambassador in Paris, had dared to send a madman with a letter of recommendation to him in Vienna. This idiot had claimed to have an invention that would allow him, the Emperor, to land troops in England independent of the winds and tides—with the aid of boiling water.”

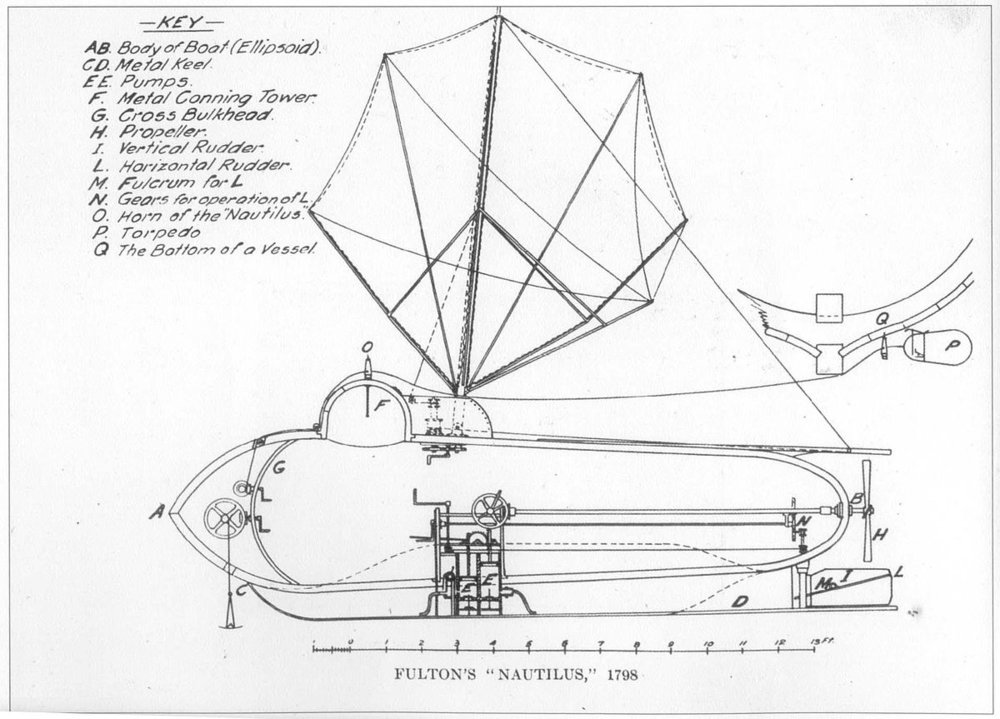

That, then, was the legendary meeting of Napoleon I and Robert Fulton, inventor of the steamship. (The anecdote beautifully conveys how absurd the key feature of a technical innovation can sound when articulated: the invasion of England is supposed to be pulled off “with the help of boiling water.”) There are some realistic details in the little story—Livingston did invest in the development of steam navigation. But it is clearly a fabrication, not least because Fulton would have been no stranger to Napoleon. Several years before, he had offered France a different ground-breaking invention, also claiming that it could decide the struggle with England: a submarine.

Fulton, a distinguished engineer from Pennsylvania who initially earned the money to pursue his technical projects as a miniature portraitist, had come to France in 1797 after encountering various setbacks in England. The antagonism between Great Britain and post-revolutionary France, whose heroes included the victorious General Bonaparte, was coming to a head; the full extent of the French public’s obsessive invasion fantasies is illustrated by articles in the Vossische Zeitung (no. 149, 1797): “The [Parisian] citizen Thilorier desires to stage an attack on England not only with airships, but also with divers. If, he quite rightly notes in his announcement, my first project has been regarded as absurd, this one will be judged still more harshly: It is possible, without great danger or expense, to march an army in battle array, with its horses, stores, artillery, and baggage, from England to France, and, if circumstances require, have an invisible fleet rise momentarily from the bottom of the sea to take the army back to France. He begs the public not to judge hastily, and promises further enlightenment in 14 days.”—And in no. 153: “Several days ago the announcement was made in Thilorier’s name that at a certain time he planned to take a stroll on the bottom of the Seine. Many curious onlookers gathered, but Thilorier did not appear. Some even claim that his airship and diver project is meant as a satire on the impending expedition against England. Meanwhile, the famous [balloonist] Blanchard offers to equip hot-air balloons to burn the enemy’s stores and occupy his forts.” That is the context; the whole decade teems with pamphlets, articles, and cartoons revolving around a French invasion of England—with Montgolfières, or through a tunnel under the Channel. And these are the years in which Fulton offered the French government plans for a submarine which he called the “Nautilus.” It was supposed to navigate secretly under the hulls of English battleships and plant mines for subsequent detonation. After Fulton had built the Nautilus at his own expense and tested it in the Seine, he was permitted to mount a trial attack, but the new boat proved too slow for the British ships. After (typically for him) switching sides, the inventor had a similar experience in England, this time hunting French navy units. As is customary with these sorts of offers, Fulton offered the assurance that this terrifying new weapon would—precisely because of its terrifying nature—usher in an age of peace. His futuristic technology served the cause of improving the world. The dialectic of weapons that will ensure peace if only they are terrible enough is not exactly foreign to us. Indeed, it held its own for fifty years, a fact that occasionally allows us to forget the madness of its underlying logic.

Friend: Well, how was the inventors’ fair?

Travnicek: Don’t even ask!

Friend: Why, what’s the matter?

Travnicek: I invented something too. But they didn’t take it.

Friend: What did you invent, Travnicek?

Travnicek: The ship’s propeller.

Friend: But that’s already been invented.

Travnicek: I didn’t know that. Such an Austrian fate.

Friend: And is that what you’re annoyed about?

Travnicek: I’m not annoyed about that, I’m annoyed that the others

did know.

—Helmut Qualtinger, “Travnicek and the Vienna Fair”

Many of the letters, pleas, offers, and notifications that passed between Fulton and the French and British governments over the years have been preserved. Among other things, they show France’s distracted interest in the bâteau poisson, an interest that did, at any rate, ultimately prompt First Consul Bonaparte to appoint an assessment panel including such prominent authorities as Laplace, Volney, and Monge. In practice, the boat proved slow and unreliable, and the end came in 1801 when Napoleon impatiently rejected what seemed a purely eccentric project. (And Fulton was a truly eccentric pursuer of projects, someone who in 1797 produced a treatise presenting his two chief obsessions—a system of inland canals and his submarine boat—as symmetrical techniques of salvation: a Universal betterment of Humanity, through a constructive system of Canals, and a destructive system of Torpedoes. This is the origin of the word “torpedo” in the sense that we are familiar with. There is an uncanny aspect to one of his improvised money-making projects: around 1800 he erected a large panorama in Paris depicting L’incendie de Moscou. There were no doubt participants in Napoleon’s Russian campaign who recalled this prophetic spectacle as they witnessed Moscow’s great fire in 1812.)

Remarkably, in many older histories—and even in the current edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (“The French government rejected the idea, however, as an atrocious and dishonorable way to fight”)—one reads that moral outrage alone held back Fulton’s contemporaries from adopting his weapon. Napoleon, in particular, appears here as a man who rejects Fulton’s plan in disgust. One should keep in mind that few people in world history—and surely none in the long nineteenth century—have been as heavily mythologized as Napoleon. We might need to go back to Alexander to find an equivalent. Part of Napoleon’s myth is definitely a certain scorn of technology—the modern technology that goes beyond the workmanlike knowledge proper to a lieutenant of the artillery. Both as a politician and as a commander he privileged the will instead. This will was presumed to be so strong that for a long time people could not quite believe in the emperor’s death. There is always a popular tendency to believe that great or notorious men are not actually dead; with no other modern figure did this rumor persist as stubbornly as with Napoleon. A vast proliferation of pamphlets blossomed solely around the fiction that he went on to serve the sultan as a Turkish commander—having converted to Islam?—and was responsible for defeating the Russian troops in 1828. In a fabulous reversal of this pious longing for mortality’s suspension, the wag J. B. Pérès, a librarian in Agen, published an ingenious satire on Dupuis’s mythography Origine des cultes, in which Christ is the sun and his apostles are the signs of the zodiac. Pérès’s pamphlet, from 1835, purported to prove that Napoleon had never existed: that he represented a solar myth, with his four brothers as the seasons, his twelve marshals as the signs of the zodiac, and his legendary Russian campaign as the sun’s path in winter.

Napoleon seems to be a magnet for legends. And to the last his legend was most peculiarly intertwined with the submarine boat. In the year 1834 newspapers reported that a notorious adventurer by the name of Johnstone had tried to sell a submarine, this time to the pasha of Egypt; this craft, too, was supposedly able to cause devastating damage by planting explosives on the hulls of enemy ships. “Johnstone avers that in this way he could destroy an entire fleet in fourteen days,” reported the Hanover newspaper Posaune, and went on: “We know that during Napoleon’s lifetime he conceived the plan of using his submarine to spirit the man of the century away from St. Helena…. But what are plans, what are projects! Johnstone lives on with his invention, and Napoleon died on St. Helena.”

What is behind the fantastic anecdote of the great Napoleon’s indignant rejection of the submarine? It reflects the principle—once dominant in Chinese historiography—that history ought not to record what occurred, but rather convey what the proper story should have been. Perhaps the curious legend of Napoleon’s contempt for the submarine reflects a retrospective dread of one of the uncanniest of weapons. Certainly it perpetuates the hope that there could be such a thing as a sovereign who disgustedly rejects certain technological possibilities.

Why, Hal, ’tis my vocation, Hal; ’tis no sin for a man to labour in his

vocation.

—Falstaff in Henry IV, Part 1, Act 1, Scene 2

In the anecdote, the great Napoleon—by virtue of the “demonic” superiority which Goethe saw in him?—scornfully dismisses the submarine; it violates the standard of military honor. But in fact one of the privileges of the great individual is that of flouting all accepted boundaries. A submarine called Nautilus—haven’t we heard that somewhere? Yes, it is the name, surely an implicit reference to Fulton, of the submarine that spreads death and destruction in Jules Verne’s novel Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. This ship is the apotheosis of the cozy bourgeois salon with its library, grand piano, and panorama windows overlooking the ocean floor—and it is the headquarters of destruction. Its captain’s name is Nemo. (His name recalls the ruse of Odysseus, who introduces himself to the Cyclops as “Oudeis,” or Nobody, so that when he finally blinds the Cyclops, the giant’s friends, hearing his cries that “Nobody” has harmed him, turn away, unwilling to help.) But Nemo is not a man hounded by divine wrath and the vicissitudes of fate, he is the inexorable master of his world, the Romantic übermensch as scientist. Like others of Verne’s protagonists, such as “Robur le Conquérant,” he pits himself against mankind. While Frankenstein, the Gothic novel’s other great inventor, constructs his artificial man out of a Faustian urge to create and fantasizes about a universal world order—it is no coincidence that he studied in Ingolstadt, the center of the Illuminati conspiracy—Nemo is and remains an adept of destruction. He is a forebear of the mad scientists whose shrill laughter echoes through the B-movies. Occasionally, as in Nemo’s case, their delight in destruction is seen as having a tragic cause, as vengeance for some great injustice. But in keeping with the narcissistic logic of these fantasies, this injustice may be something purely banal, a personal slight. This is beautifully depicted by the great comics artist Jacques Tardi, second to none in his loving evocation of the Belle Époque with its archaic yet uncannily menacing technical apparatuses, that realm between the museum and the industrial laboratory. With images recalling a film by Georges Méliès, with the rhetoric of the maniacally eccentric mad scientists of the Grand Guignol, his classic Le démon des glaces (1974) takes us inside a titanic Arctic iceberg at the center of a zone of inexplicable ship disasters. The young hero wakes up there after the sinking of his ship; standing in front of him is his uncle, presumed dead, who had long been occupied with strange experiments. Now he and his colleague, two classic savants fous, strike up the litany of the aggrieved outsider: “At the university, we were young and naive and still labored under the puerile notion of working for the good of humanity. But as the years passed and we suffered identical humiliations, we realized that it was fruitless for men of our mettle to try to improve the lives of those idiots, indifferent as they were to our discoveries and ever eager to drag us through the mud.” Stories of this kind are miniature melodramas of wounded narcissism, and in passing they say a good deal—almost everything—about our lust for armament.

And she has been down in the depths of the sea.

—Ibsen, The Wild Duck

Whether plying the turbulent seas of childhood fantasy, as in Woody Allen’s Radio Days and Gahan Wilson’s exquisite comic strip Nuts, or setting out to war as Das Boot, the military submarine is a German legend, a triumph of World War I. There is a growing awareness that the greatest memorial to all the shades of this war’s lunacy, including the complacency of daily routine, was created by Karl Kraus in his epic drama The Last Days of Mankind, written “to be performed on Mars.” But the precision with which Karl Kraus analyzed the preconditions of this lunacy has not been broadly recognized. Exploring Wilhelminism under the heading “The Techno-Romantic Adventure,” he shows that we are no longer able to grasp our own technical capabilities. Their implications outstrip our moral imagination, and we take refuge in romantic phrases—in an age of poison gas and flamethrowers, Wilhelm II liked to speak of “sharply honed swords.” One of the key scenes in Kraus’s vision unexpectedly ushers in Leonardo da Vinci. Amidst the endless-seeming procession of “apparitions,” like Shakespearean phantoms, that concludes Scene 55 of Act 5 of The Last Days of Mankind, we behold an “old-fashioned workshop,” and Leonardo is heard: “—and I shall not write down the why and wherefore of how I manage to stay under water for as long as I can; and I will not publish or explain it, because of the malign nature of man, who would only use it to commit murder on the ocean bed by breaking the hulls of ships and sinking them, with all the people aboard—”

This dramatic quote leaves out the conclusion of Leonardo’s remarks. In the original, they end: “Nevertheless I will impart [other methods], which are not dangerous because the mouth of the tube through which you breathe is above the water, supported on air sacks or cork.” In other words, Leonardo restricts himself to conveying strategies in which the attacker remains vulnerable even under water, as his bocca di canna reveals him to his target. Leonardo da Vinci was a man who (in a famous letter to Lodovico il Moro of Milan) tossed out a single sentence describing himself as a painter, while commending himself at length and in detail as an architect and engineer for civilian and especially military projects of all kinds—what made this inventor of cannons, forts, scythed chariots, machine guns, and battering rams hold back, filled with reluctance and revulsion, when it came to setting down notes for a submarine? We do not know. One might suppose it is just another example of his mantra “I shall not write…” intended to protect himself from imitators and competitors. But “by reason of the malign nature of men” makes his reasoning apparent.

It is difficult to gauge Leonardo’s motivations for writing these words. In any case, for Kraus, looking back, his stance became a towering example of necessary renunciation. The significance of this passage from The Last Days of Mankind lies in its contrast with the barbaric smugness of the patriotic zeal for the German submarine war (“We blow them up and sink them soundly, but sensitively too!”). In Act 5, Leonard is immediately preceded by the twelve hundred horses Count Dohna drowned, and immediately followed by singing children’s corpses “on a piece of flotsam,” two of the twelve hundred victims of the Lusitania, a passenger ship famously sunk by a German submarine. When the Basque government issued an information brochure in May 1937 on the bombing of Guernica—which Franco’s regime and the Nazis tried to pass off as arson committed by fleeing Basque troops—it couched the historical truth of the German air raid in words citing two World War I atrocities: “We know who the murderers were—it was the ones who sank the Lusitania and burned the University of Leuven.” Both horses and children are the victims of an explicitly technological force that flies in the face of nature. By selectively quoting Leonardo, Kraus salutes a stance that has been lost, or perhaps was only supposed to have existed—the ability to reject a technological advance despite its feasibility. For Kraus, this appears as mankind’s final chance for survival in its last days.

A good deed is easy to do, but it is hard to decide whether it is called for.

—Leonid Leonov, Notes of a Small-Town Man

One of Billy Wilder’s lesser-known films, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, features perhaps the most charming appearance of a figure who has come to epitomize old-fashioned narrow-mindedness, though there is clearly much more to her than that: Queen Victoria. The film plays with Holmes’s haughty romantic inexperience (already emphasized by Conan Doyle) by having a woman lead the master detective astray—a lady whose Belgian-French name conceals the German spy “Ilse von Hofmannsthal.” The plot turns on the disclosure of a project by the British intelligence service: they are testing a submarine manned by midgets and disguised as the Loch Ness Monster. The climax comes when the new weapon is finally presented to the Queen, played by Molly Maureen. She reacts with undisguised horror and disgust. This sort of weapon is “unsportsmanlike, it is un-English, and it is in very poor taste.” (Perhaps we are hearing, in a different national costume, a distant echo of the Napoleon anecdotes.) She goes on: “Sometimes we despair of the state of the world. What will scientists think of next?” The context is ironic; the final question, as such, is not.

The Queen’s attitude in Wilder’s film, the British crown’s brusque rejection of such a weapon, permanently conflates the historic and the mythopoetic, seeming covertly linked to her most famous historically documented utterance. Everyone knows the words; they were recorded late (in the memoirs of Lady Caroline Holland, 1919) and without reference to a specific situation, but stand as a sort of epitaph which the era chiseled for itself: “We are not amused.” I believe we need to hear these words anew. If anything can save us, it might be the constant meditative repetition of this mantra, with an additional version for technological contexts: “We are not interested.” This might help us to grasp that our automatic interest in the next technological stage of destruction or amusement is the common denominator of our annihilation (by amusement, by destruction).

Truth thrives in the margins. In closing, let us take a look at an American comic book published in 1942—though, crucially for this context, based on daily comics from November 30, 1936, to April 3, 1937. This Disney comic, by Floyd Gottfredson and others, is called Mickey Mouse and his Sky Adventure, and is still written very much in the spirit of the nineteenth century. An adventure in the sky, it begins with Mickey and his bumbling, indispensable companion Goofy flying along in a two-seater airplane (somehow they seem to be connected to a military base). An automobile flies past, and an elderly gentleman greets them amiably. It turns out that this Doctor Einmug has discovered “some new kind of power with a tremendous force”; he is already being pursued by foreign spies. One of them—a familiar figure, Black Pete—tries to steal the revolutionary formula, but Mickey manages to foil the attempt. But though Colonel Doberman has entrusted him with the hysterically urgent mission of finding out this information (“We must get it before someone else does!”), the scholar refuses to share his knowledge.

Doctor Einmug is a kindly scientist of almost magically advanced intelligence. Remarkably enough for 1942, the year after Pearl Harbor, and even in 1936 reflecting a generous infatuation with tradition, he is identifiably a German scientist in the venerable old-school manner. At a time when American comics were deploying all their superheroes against the Nazis, here—anachronistically, nostalgically— we see a roly-poly little bearded scholar with a white lab coat, pince-nez, a top hat (or a black, Biedermeier-era cap), and a long-stemmed pipe who speaks with a thick Teutonic accent. His name is a pun on “Einstein”—already a legend, as this indicates. Because the “stein” can mean a beer tankard, it is replaced by “mug,” a slang word for “face.” This unlikely and unprepossessing hero proclaims the reason why no one can be allowed to possess his knowledge: “I am sure you will understand why you can neffer haff mine formula! Der world iss not yet ready for mine invention! It would bring only sorrow… und fighting… und killing!” Dismayed, Mickey asks: “But, Doctor Einmug! What are you gonna do with your formula?” “Don’t worry, mine friend! Nobody else will get it! You will neffer hear of it again… or me either!” And a few minutes later Dr. Einmug escapes to another planet, along with his laboratory island that floats amidst the clouds. Mickey and Colonel Doberman philosophize bemusedly that they’ll never be able to talk about this adventure: no one would believe them. “All we can do is just shake hands on it… and forget the whole thing!” Perhaps forgetting is just the art we need to learn; it would parallel the masterfully abrupt disappearance of the fugitive scientist. Harald Weinrich’s great study Lethe: The Art and Critique of Forgetting ends with a reflection on the “oblivionism” of science—the scholar’s sense of powerlessness when faced with masses of material that mount ever higher and ever more rapidly. Might we hope for a sequel that would write the epistemology of active forgetting, the sober and rational refusal to know, the renunciation of a possibility?

This essay appears in Joachim Kalka’s Gaslight, out June 6th from New York Review of Books.