In a carful of New York media men en route to a Catskills bachelor party the evening before neo-Nazis stormed Charlottesville, I declared Trouble Man the best Marvin Gaye record of the 1970s. This was a gaffe; I shouldn’t have said it. Michael was particularly incensed: “That’s just Marvin fucking around on a keyboard.” He wasn’t wrong, and by most standards mine was a contrarian take inspired by confused chronology (What’s Going On came out in 1971, not 1968), an overeagerness to impress new friends, and a nostalgia for the jukebox at Vaughan’s Lounge, my local haunt when I lived in the Bywater. I’d spend fistfuls of bar change on the title track of the album, the soundtrack to a Blaxploitation film about a South Central gumshoe named Mr. T., Gaye’s falsetto coos of “I didn’t make it, sugar, playin’ by the rules” retroactively justifying to-go drinks regretted and only half remembered.

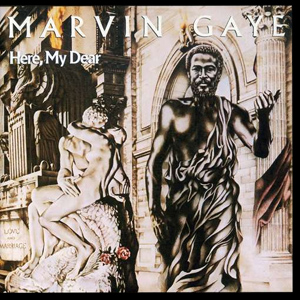

And then there’s Here, My Dear.While no one would in good faith or sanity rank it as Gaye’s crowning achievement, I’ve always been partial to runners-up. Divorce is a leading cause of artists’ second-best creative output: Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, Lou Reed’s Berlin, and—if you happen to be a Tusk devotee—Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours. Here, My Dear chronicles Gaye’s split from his first wife, Anna, elder sister of Motown Records founder, Berry Gordy, in 1977; its cover art features a toga-clad Gaye in front of a burning temple with LOVE AND MARRIAGE etched into its façade. I am not divorced, nor do I intend to be; quarantine has only pleasantly regressed my marriage to the honeymoon stage. Still, once it became clear that the gym would not reopen any time soon, the faux sincerity of Gaye’s spoken-word intro on “When Did You Stop Loving Me, When Did I Stop Loving You,” its chugging bass and cowbell, lured me into exercise. Lyrically, Gaye is unsparing: his accusations of dishonesty (“If you don’t honor what you said, you lie to God”) give way to greed (“If you ever loved me with all your heart / You’d never take a million dollars to part”) and hypocrisy (“What I can’t understand is if you love me / How could you turn me in to the police?”). But as always, his voice is the selling point, and the bittersweet candor Gaye ekes out from the root of the F minor chord sustained over Nolan Smith’s muted trumpet as he sings “Do you remember all of the bullshit, baby?”—lending the note an impression of dissonance though musically it has none—brought me to target heart rate, or something like it, shimmying sock-footed while Adriane took a Zoom call in the other room.

Critics dismissed Here, My Dear upon its release, and it was a rare if premonitory commercial failure for Gaye. Stylistically, the album reconciles his mid-career soul period with the “Sexual Healing” cocaine disco of his final years in European tax exile. Initially conceived as a “quickie” (per Gaye himself in the liner notes) to bring his divorce proceedings to a settlement—the title is meant to be taken literally—Here, My Dear became something else entirely: an experiment in freeform funk and spontaneous prose, rivaling Jack Kerouac’s compositional method (“first thought, best thought,” as Ginsberg put it) at the same time that Iggy Pop was doing the same in his collaborations with David Bowie (The Idiot and Lust for Life), six thousand miles away in Berlin. Robert Christgau called Gaye’s self-involvement “open and unmediated,” a hubristic disaffection both futuristic (see “A Funky Space Reincarnation”) and punk: a kiss-off to history, a look in the mirror at once honest, indulgent, and overdue.

It is not to Germany, where I’ve never been, nor to New Orleans, Phoenicia, the Motor City, nor to Los Angeles, Gaye’s final home, that Here, My Dear transports me, but to a vision of life as it was, sarcastically deromanticized with Roland synths and a saxophone section and Gordon Banks on guitar. I slipped “When Did You Stop Loving Me” onto a playlist naively titled “The End of Time” last December, a soundtrack for the New Year’s Eve party I had decided to host, if you can believe it, in order to avoid going out. Our last before the fall. In six and a half hours on shuffle, Marvin appeared at just the right moment. As much as I’d like to remember my friends dancing to the music as I do now, alone, I know their appreciation was distracted and diffuse in the way only possible in a room full of people. “Still I remember some of the good things, baby,” he sings, breaking up with the past. “Like love after dark and picnics in parks / Those are the days I’ll not forget in my life.”

— Andrew Marzoni

Brooklyn, day 49