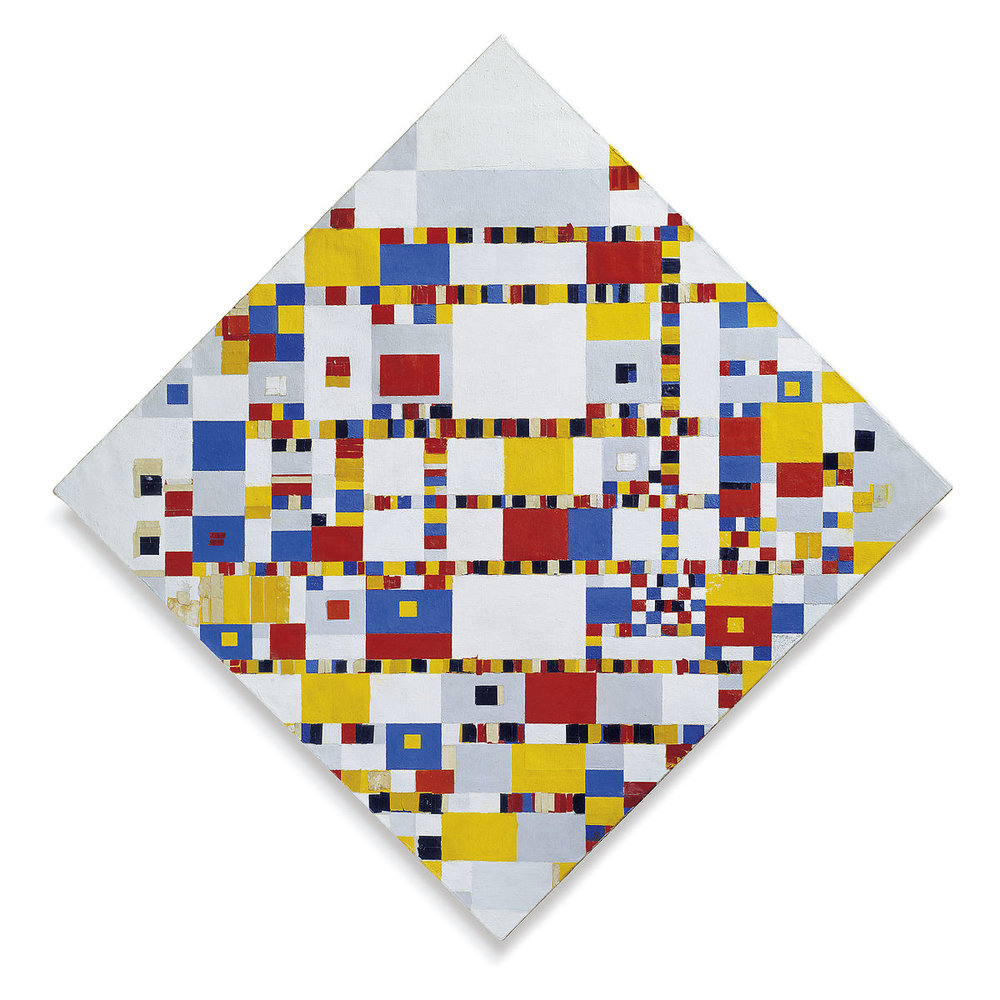

When the artist Piet Mondrian died in the winter of 1944 at the age of 71, he was in the midst of working on a painting he had told people would be the definitive expression of his aesthetic ideals. The work, entitled “Victory Boogie Woogie,” in homage to American jazz, had absorbed his entire focus for more than a year.

In the last ten days of his life, while suffering from acute bronchitis, he worked on the painting to the exclusion of all else, tacking onto the canvas small squares of colored tape, ignoring his rapidly declining health. He worked until he collapsed. Friends discovered him passed out in his studio and rushed him to the hospital where, a few days later, he died of pneumonia. Art historians and critics have since called the diamond-shaped canvas covered in tiny pieces of colored tape that he’d left behind on the easel Mondrian’s last great, unfinished masterpiece.

Almost immediately afterward, and for more than seventy years since, people have tried to figure out what the painting would have looked like if Mondrian had finished it. Over the years, Mondrian friends and aficionados have proposed various final versions of the painting, sometimes based on color-charted logical formulas or mathematical algorithms, and artists have made lots of copies, hoping to both preserve the image, and to explore its logic. Once every few weeks, the Gemeentemuseum, which owns the largest collection of Mondrian works anywhere in the world, still receives an email or letter from someone who claims to have discovered the mathematical proof that would solve “Victory Boogie Woogie.”

“They all break down somewhere,” says Hans Janssen, chief curator of the Gemeentemuseum, and author of a groundbreaking biography of Mondrian, Piet Mondriaan: Een nieuwe kunst voor een ongekend leven [A New Art for a Life Unknown]. “The reason is—and this is what no one understands about Mondrian—that all his work was intuitive.”

This year, the Netherlands has been celebrating the 100th anniversary of De Stijl, the art, architecture and design movement founded in 1917 by Theo van Doesburg, whose fine art component was refined by Mondrian, a key participant in the movement, which was also known as Neoplasticism. In his essay, “Neo-Plasticism in Pictorial Art,” van Doesburg suggested that art should jettison “natural form and color,” “ignore the particulars of appearance,” and instead “find its expression in the abstraction of form and color.”

“Victory Boogie Woogie” was supposed to become the consummate expression of Mondrian’s aesthetic ideals. In mid-May 1942, he told his then-girlfriend, American artist and journalist Charmion von Wiegand, “Last night I dreamed a new composition.” He was in a state of excitement, she remembered in a 1961 article, and...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in