In the late spring, as uprisings bloomed around the murder of George Floyd, we started thinking about Nikki Giovanni, which is to say we were thinking about Black sociality, Black art, and the manifold agreements and disagreements that flower among us. We were thinking about Black dialogues. In November 1971, Giovanni herself participated in a famous discussion with James Baldwin, which was filmed for “Soul!” an English television program. When the dialogue took place she was twenty-eight, and he was forty-seven. There was lots of accord in that conversation, but there were also fractures, especially across gender and generational lines. That conversation, which was ultimately transcribed and published in 1973 as A Dialogue, provided a model of how to publicly discuss issues of critical importance, and a way to productively disagree. Throughout her career, Giovanni herself has demonstrated dedication to Black discourse, as her work juxtaposes internecine struggles within communities of Black people alongside their issues with America writ large. Her writing is interested in the relationships between Black literature and pop culture, between unity and productive debate, and also, as in her “Poem for Aretha,” between Black art and commerce, Black stars and their productivity, and the public’s consumption of those people and their work.

Her first book, Black Feeling, Black Talk (1968), is formative in the canon of Black American poetry and poetics, and contains many meditations on intellectual and emotional connection between Black people. Here she is, in a poem called “You Came, Too,”

I came to the crowd seeking friends

I came to the crowd seeking love

I came to the crowd for understanding

In another, “Poem (For TW) she writes,

You had tried to fight the fight I’m fighting

And you understood my feelings while you

Picked my brains and kicked my soul

Black Feeling, Black Talk’s title became a spiritual motto for the kinds of engagement we were seeking in late May and June; talks between the two of us emphasized the importance of kinship among Black writers. In this spirit, we also wanted to talk with folks who are asking the questions we’re asking. In this moment of resistance, when the world is in many ways hyper-attuned to the experience of Black life and death, we wanted to invite Black writers we admire to talk about their relationship to writing, the roles contemporary writing of all genres can play in advancing racial justice, how (and why) to write about our complicated feelings without turning our joy and pain into a spectacle, and how the media and publishing industries perpetuate systems of oppression, tokenization, and fetishization. We hope that the greater purpose of these conversations will be as a resource to other Black writers and readers who are turning over all of these ideas right now. We’d like to connect this critical moment to others in the past, and contribute to a continuum of Black literary responses to issues of urgent importance to Black writers, and more importantly, to all Black people. We hope that this round table can connect not only past and present, but become a spark for future conversations that ensure we keep thinking about how, exactly, Black lives matter as we move further from the turmoil of this past spring and early summer. The first installment of our six-part series involves Black writers and editors who work in the media. Our panelists are Cassie Owens, a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer; Danielle A. Jackson, a critic and managing editor of Oxford American; and former BMI Shearing Fellow Hanif Abdurraqib, GEN Magazine editor and author of They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, Go Ahead In the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, and the forthcoming A Little Devil in America.

—Niela Orr and Ismail Muhammad

I. “WHO BENEFITS FROM THIS MODE OF PRODUCTIVITY THAT I’M OPERATING IN?”

NIELA ORR: How are y’all feeling right now?

DANIELLE A. JACKSON: From moment to moment, honestly it varies, right? In this moment, I feel grounded and well-fed and well-rested, but that’s because I’ve been really deliberate over the past few months about just going back to the basics of what I’ve learned about how to take care of a body. And that’s something that I started being really deliberate about even before the pandemic. I recently moved from New York to Little Rock for a new job, so I’ve been feeling a sense of placeless-ness, even before the pandemic really erupted in the United States in earnest, and then obviously after the uprisings happened. I guess I feel uprooted and to counteract that, I’ve been making sure I care for the very basic needs of my body. That also includes keeping in contact with my family as much as possible, having as much interaction with loving friends as possible, listening to music that is a part of what I consider the continuum of Black intellectual tradition that is nurturing and helps to grow and build our resilience. So, I guess I’m feeling bad but I’m working on that so that I can be of some use.

ISMAIL MUHAMMAD: I’m so curious about that process of care-taking and nurturing. What impact does that have on your work? And I guess I’ll ask all of you that question later, because I think for me it’s been that work and care have not gone together necessarily, for me at least.

DAJ: Yeah, I’ve been trying to figure out how to take naps or how to be okay with maybe not doing a good job on some things, or also saying no. I’m new to a city and I’m new to a job. I moved to work for Oxford American at the end of January, so I feel like you’re not supposed to take any days off your first ninety days of work. That’s what I learned; I don’t know, I have old parents. But I had to take some days off and just forgive myself, and just embrace being imperfect and not having the cognitive space to do everything to the best. I’ve been just reassessing, what is my best? My best is not what my best was this time last year.

CASSIE OWENS: I feel like I’ve been in a similar process of taking it day by day and doing a lot of self-care just to be able to continue to keep taking it day by day. For self-care I’ve been doing a lot of gardening and trying to take care of plants and grow things that have ancestral connections. So that’s been cool. And I’ve been having conversations with my grandparents about what they grew when they were still in the South or when their families were still in the South. So that’s been cool and helpful to me. Elder separation is hard because I’m out reporting, not all the time, but enough for me to feel like I shouldn’t be in contact with them. So being able to talk to them on the phone about food and gardening has been really helpful for me.

HANIF ABDURRAQIB: I’m in Columbus, Ohio, where I was born, where I was raised, and where I’ve lived most of my life, and I think some of my work here, my “on the ground work,” is very separate from my work as a writer and has always felt that way. And so I think my frustrations and my joys in the former are definitely informing my ability to operate in the latter space. So I’m as angry as people in the country are, but locally I’m angry about the mayor and the police and the way I’ve seen my peers treated and the way I’ve been treated during protests and during actions like trying to get protestor supplies. But, I’ve also been really uplifted by our young folks here, and I’ve been really uplifted by the organizations in the community that are kind of still pushing forward despite everything.

Danielle said something about imperfection and being imperfect, and I was thinking about that. I really loved hearing that. When the pandemic started, I was baking a lot, and I don’t know shit about baking. So I was kind of making things with the understanding that I would be able to fail, you know? It was good to make something and have no expectations beyond making a thing for myself that might not be perfect or that no one else had to consume. I would occasionally, if I was making, like, a layer cake— I know this is an extended metaphor but it’s getting to its point —if I’m making a layer cake this thing would happen where the actual cake would get fucked up. Like the middle would tear a little bit or whatever, and I would get so down, I mean like, immensely down on myself, you know what I mean? But in the process of putting the cake together, icing and all that, I realized, Yo, that shit actually doesn’t matter. Like no one can see the massive imperfections under the frosting and the layering and the whatnot. And so I started to think about the fact that this is probably not healthy but it’s what I can do at the moment. I’ve started to maybe think about my movements through the world as kind of that same thing, like how can I dress up the imperfections and still, at the end, be good to myself?

NO: I love what y’all are saying about imperfection and expectation and I love that you were able to talk with your family, Cassie. I’ve been spending a lot of time with my mom and one of the main things that we do right now is watch The Real Housewives of Atlanta and The Parkers together. We’ve been getting a lot of joy out The Parkers and the slapstick quality of that show. I’m writing about slapstick comedy and Black bodies in that context, how interesting, hopeful, and, depending on the show or film, downright troubling, it is to see these people who are hurt but they pop up again as if nothing happened. It’s really really complicated and it’s super layered. We’ve been having a great time watching that and listening to Gil Scott-Heron and trying to relax. Sometimes I worry that I’m relaxing or sleeping too much; I worry that I’m not doing more, and then I have to remind myself that resting is important. I’m reminded of something Brontez Purnell said about resting in a 2019 interview he did with The Believer. Jenn Pelly, who talked with him, asked him how resistance is manifesting in his work, and he said that sometimes even getting up out of bed is resistance. Resistance looks a lot of ways.

I have to remind myself that I’m resting to store up the energy it takes to resist, and also the energy expended in experiencing joy. Echoing Brontez, sometimes the fight looks like going to Starbucks, sometimes the fight looks like just walking out into the world, sometimes it looks like being at a march or protest. So, anyway, thank y’all for saying all of this. Your insights really are a reminder to be kind to myself.

HA: And I think too, the work will be there. What I’ve been seeing now is a lot of organizers and a lot of people in my community and my extended communities are getting so down on themselves for what they’re physically capable of, and now’s not the time to fuck around with that, you know what I mean? Like, to be fair, it’s never been the time to fuck around with that, but now specifically is not the time to fuck around with that because on the other side of whatever your health or your world or your body needs, there will be more work undoubtedly, you know what I mean? And the work that will remain absolutely needs people who are healthy and enlivened and not pushing themselves to a limit that they can’t bear.

NO: What you’re saying, Hanif, also connects to something that Octavia Butler once said in an interview on the making of Kindred about heroism and the ways in which protest and survival can take different forms. To paraphrase her, there’s a kind of extreme, reactionary response to anti-Black terror that she’d observed, which means potentially hurting people—she’d referenced a friend who talked about killing people as retribution for racism and Black Americans’ stalled progress—but according to her, there are other modes of resistance and one of them is just “surviving and hanging on and hoping and working for change.” That quiet mode of resistance—making sure you make it to the next moment, the next year, etc., is so powerful and connects to Black Americans’ ancestral survival. I’ve been thinking about that more and more these days.

IM: That makes me think, in the time that you all have been able to do work, what has this new perspective on imperfection and quiet modes of resistance, how has that affected how you think about your criticism, editorial work, or reporting? How are you thinking about that differently at this point?

CO: I’ll say for me it’s difficult to even remember some of the things that I’ve written over just the last, like, two months. So I feel like my perspective on perfection has changed a lot because I can’t even remember when I wrote some of the things, you know? What’s happened in the world in that period of time has changed the way that I see what it means to be productive. I’m doing a lot of things all the time for work and that makes me feel like I should celebrate things differently, like I’ve bought in way too much to what other people think productivity is.

HA: Yeah, it’s funny. I was joking with a friend two weeks ago that I think maybe prepared me for this moment because I’ve been reconsidering a lot of ideas around productivity for a long time. Last year I put out two books, one at the top of the year and one near the end of the year, and I spent most of the year on the road for those books. I did like 74 readings, and that felt untenable to me. Come November, I was asking myself questions like, “Who benefits from this mode of productivity that I’m operating in? Because I don’t think it’s me and I don’t think it’s any writers that are looking to me for guidance or anything.” I spent a lot of time from the top of this year to now working on this massive passion project, this playlist and music archival project that no one asked me to do, that I’m not getting paid to do, it’s just a thing that’s fun. It lets me seap myself into interests of mine that weren’t being fulfilled. By all accounts I’m still doing too many things, but I think I’ve reframed my idea around productivity by asking who my productivity benefits and what is the value that I’m getting from it, and does this contribute to my survival and the survival of people I care about?

DAJ: I guess for me I’ve just been trying to give myself more time with my various projects. I’ve been asking for what I actually need, resource-wise. I don’t even really mean like financial resources, but if there’s books I need that I know that I need to complete something, I’ve just been a lot less shy about asking for sustenance. I think I’ve been wanting to work towards that anyway for the past few years but I definitely feel emboldened because I’ve run up against limits and I realize that there are just things I can’t do without certain resources. I can’t just white-knuckle it, so I’m asking for help.

II. “WHAT DO YOU SAY ABOUT EVERY OTHER BLACK PERSON EATING IN THE COUNTRY?”

IM: That question about who our productivity is benefitting seems especially crucial right now. I don’t know about you all, but I’ve had like seven white editors email me in the last week to ask if I had anything and it’s like, “No I don’t have anything to say about this particular moment at all, and even if I did, and you were paying me a nice sum of money, I don’t know who it would benefit to have my writing out there on this particular topic.” I feel like I’ve had to rethink who I’m writing for, and what I’m writing for exactly. Obviously in part for money, but what are the other reasons that I’m producing work at all? If not for money and a byline?

NO: A few years ago, when a white supremacist killed nine Black people in Charleston, South Carolina, I was asked to write about what happened, and, wanting to have something to say, wanting to address the moment, feeling honored that someone asked me to write, I did write about what happened and I think I wrote about it within like a day, or five hours, or something crazy. And as soon as I sent the piece to my editor, I remember feeling so… I remember feeling like it was a mistake, you know? Maybe I can still stand behind everything I said in the piece intellectually, but it did not feel right emotionally to write about that while my feelings were still raw, while I didn’t have enough time to actually process it. I vowed at that moment to never peg my feelings to an event, you know what I mean? But it’s hard because that’s the nature of the business, too. If you need money, you’re a freelancer, you’re called to write and you may need that $300 or $500 or $700, whatever it is. Anyway, it’s just a tricky kind of thing to negotiate. I think especially because the bottom has fallen out of this industry in so many ways, I worry and wonder and marvel at the folks who are able to produce work they’re emotionally satisfied with in these moments of crisis because it doesn’t always feel right.

HA: I have had editors kind of like reach out to me and when I was pretty frank — y’all I can’t write, and then they’d hit me back and say, “So do you know any other Black writers?” It’s like, no, no, do you know any other Black writers? that’s the question, you know what I mean? The question isn’t to hit up Black writers and ask, “Do you have any…?” Like, “No, why isn’t your phone book or email address book of Black writers more robust? Why are you coming to me, who does not work for your publication?” So that’s what I was going to say that’s maybe too real.

Another thing is, I don’t do much timely work anymore, I’m actually writing a thing right now about [laughs] how two of the Christopher Columbus statues here are coming down and I got asked to write about it and I felt like I could and should write about that because I was worried that someone who does not live here would write it, you know what I mean? ‘Cause I know the work that went into getting those statues the fuck out of here, and it seemed important to me that someone who lived here and lived through that wrote about it. But it’s been hard for me to want to remind folks that, for a lot of Black writers, this is not our work, our capital “W” Work, right? Because I think this happened at the start of this where a wave of white people were just like, “I gotta follow these Black writers for answers, I gotta read.” And as I’ve had to remind people multiple times, you know you followed me looking for answers about race, you’re really gonna catch me doing deep dives about, like, Alanis Morrisette, you know I mean? My work on the page has always revolved around analyzing music and pop culture. So much of my work as a writer and editor is to make sure that Black people have the ability to write about more than just moments like the one we’re in right now, and a big disheartening thing for me has been to live through this moment and again see editors scrambling to get Black writers to write and then undoubtedly those same editors will vanish when those Black writers want to write about, I don’t know, ice cream or whatever the fuck.

DAJ: Yeah, for me as an assigning editor and a person who writes on assignment, within the institution I work for, in which I make assignments, it was just really important for me to say that if we’re going to be reaching out to Black people during this moment we need to be saying that you can write about whatever it is that you want to write about. And also I was heartened because I felt like where I work right now had already had a history of contributors of color and I worked for places before that didn’t have that and had to scramble, emailing people trying to find out, “Do you know any Black writers?” or “Hey, can you write about race right now?” because race is “happening,” to quote Lauren Michele Jackson, but if you really knew, if you were doing your homework, if you were actually good at your job, you would already know a long list of people who were writing about race and you would also know that people are writing about race without even having to say that word. So, yeah, I mean, I don’t know, I felt a conflict even asking people for work, but in asking people for work I just wanted to make sure people could do whatever they wanted if they were able to do something. That doesn’t really satisfy my conflict either but that was a step toward satisfying it.

NO: I have questions for all three of you in this vein. Cassie, your work is so amazing in general, just in the way that it spans the incredibly quotidian and opens up to these larger questions of American history. I was struck by your piece on Vertamae Smart-Grosvener’s book Vibration Cooking and the fact that the essay was unveiled in a Juneteenth editorial package on the Philadelphia Inquirer‘s site, but it absolutely had nothing to do with Juneteenth, you know what I mean? It was so obliquely related to it, and I just thought, Oh this is so subversive. I thought, Maybe an editor is organizing the essay in this way in order to get more eyes to come to the website. It doesn’t really make categorical sense, but it’s kind of a Trojan horse; perhaps Juneteenth was a perfect vehicle to get Smart-Grosvenor in the Inquirer’s pages despite her evergreen appeal. The fact that you took this time on Juneteenth to not write directly about Juneteenth was so, so funny to me and just so heartening as well. Can you talk about how that editorial decision was made?

CO: Yeah, so Jamila Robinson, the Inquirer‘s food editor, made that decision, and Jamila is newer to the Inquirer. She just came aboard, probably in like February. And yeah, basically, I asked Jamila, “Are you the first Black food editor at the Inquirer?” And she was like, “I’m the second Black food editor at a major American daily newspaper after Toni Tipton-Martin, so yes.” We need more Black people writing about everything. We just do! We just do. We need more Black folk writing about everything. So she had the plan of doing a Juneteenth food section, and I had actually pitched doing a story on Vertamae Smart-Grosvener because the fact that she’s from Philly is not often mentioned in her story or it will be just kind of included as a passing mention. And Philly does a pretty abysmal job of actually honoring Black folk who make contributions to food. Not just in Philly, but those working across the country. Philly doesn’t really honor those people a lot. So I pitched it a while ago and she basically hit me and was like, “Can you write this for Juneteenth?” And I was like, “Sure, let’s do it.”

DAJ: This is more of a question, but isn’t Julie Dash working on a film about Vertamae Smart-Grosvener?

CO: Absolutely, yeah. I spoke to her for the story. She’s been working on it for years, but she only has a few more interviews to do, she was telling me.

NO: Yeah, I feel like the fact that Philly doesn’t honor her speaks to our racist history in general, but I also think it speaks to the way Black work is classified in ways that are sort of neat and tidy. So her writing gets lumped in almost exclusively with writing about Southern cooking but there’s so many different ways to classify and think about her work. I’m glad you made that point Cassie.

CO: Oh, thank you. One thing that’s come up is that often Black food will either be Southern or diasporic. And it’s like, what do you say about every other Black person eating in the country?

III. AN OVERHAUL OF OUR IMAGINATIONS

NO: Hanif, I wanted to ask you about performance, particularly in this moment. I know that you’re working on a book formerly titled They Don’t Dance No Mo,’ about Black performance, and I’ve seen you read a little bit from it in Philly and in Vegas. I want to ask about the performativity of this moment and the ways that a lot of corporate, media, and literary entities are doing this performative outreach to Black writers, which you’ve just been talking about. Are there any connections between the asks and the expectations of Black contributors, Black artists, Black writers, Black people right now, and the performances that you’re studying?

HA: Yeah, actually thankfully I’m finished with the book. It’s now called A Little Devil in America, which is a line from Josephine Baker’s speech at the March on Washington. You know, what has been funny–I use funny in a way that we all understand “funny” to mean here–has been watching the corporations pivot abruptly from the like, “Here’s how we’re handling COVID” email to the “Here’s how we discovered racism” email. And it happened so quickly. It happened within a week’s time. The ones on Juneteenth were so wild, too. I got an email from Hulu that said, “We’re reflecting on Juneteenth.” And I thought, “What does that even mean? You’re a streaming service.” And so I think there’s so much anxiety about not wanting to be on the “wrong” side of the moment.

Sorry to veer into emo music, but I was scrolling the internet and I saw that Chris Carrabba of Dashboard Confessional got in a pretty bad motorcycle accident. And he was in a hospital for like 10 days and during one of those 10 days was the Black Out Friday day and he didn’t post anything because he was in the hospital. And a couple days after, he wrote a statement from his hospital bed that said, “Listen, I was in a bad motorcycle accident, but I want people to know that I think Black lives matter.” I was like, man, isn’t this so weird that the urge to not be on the wrong side of the moment has created this interesting idea of — and I don’t mean performance dismissively — but this idea to perform the right thing to do or attempt to perform the right thing to do or say. I think what happens so often, particularly for white folks, is that they’re thinking about how to perform the correct way nationally, if not globally, like how to get down with the right campaign or do the right thing. I think the better question is how to do that locally, but the imagination of the needs of Blackness in America is so small and so it comes to this thing where it’s like, “Well, a Black person told me to put this on my Instagram and so I’m gonna do this because it’s what Black people need.” It’s like, well, what about a Black person who lives down the street from you? Or the Black people who are in the streets protesting? What do they need? This isn’t answering your question directly but I’ve been thinking a lot about how white people performing for Black people has been this thing that’s maybe turned what I was writing about on its ear, you know what I mean? It’s taken the ideas I was chasing after in my book and put them through a weird fun house mirror. Because what I am seeing is that there are a lot of people in the country who are not Black who don’t know, who also have not talked to many Black people, and therefore don’t know how to do anything but perform a version of themselves that seems as though it will get them past this checkpoint to the next one. And when we talk about doing things to survive to the next moment, I’m thinking about that too. I’m thinking about non-Black folks who, instead of really engaging, not only with themselves but with their actual communities and with the people in their communities, ask, “How do I join the national conversation on race and do it in a way that comfortably gets me across…” I know I’m being very referential and I might be aging myself here but it reminds me of The Oregon Trail, the computer game, where you have to get across the river in a wagon but if you fucked up or you tried to go across too deep in the river your wagon would slowly break down and then you would be underwater by the time you got halfway through. That’s what watching this is like for me. People who are unequipped to ford the river in their wagons attempting to go to the deepest part of it and expecting to stay afloat.

NO: Danielle, I love the work you’ve done in Bookforum. Most recently, I enjoyed your amazing review of Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age. I really, really love the last sentence of it. You say, “Because the realities of class and race bump up against the realities of economic collapse and environmental calamity, we would deepen our understanding of the era by looking to a wider group of voices to embody it.” And then in thinking about your work in this moment, it appears to me that the search for diverse voices might be happening right now, even if in certain shallow or circumscribed ways. But I want to put the question to you. Do you feel like that search to deepen the conversation by finding a diverse group of voices is actually happening, and if it is, do the efforts feel temporary or sustainable?

DAJ: I think it’s performative. I don’t think performative actions are inherently insincere, but I mean, from my experience in the publishing industry to date, I don’t have a lot of faith in whatever this wave is being like some kind of sustainable, new way of thinking. I would love to be mistaken, but I feel like we’ve had waves before where there’s been strong interest in supporting and putting resources behind Black art and then it washes away. I feel like that was happening in the past few years after the Obama era. I feel like that was like some glory years where we had Melissa Harris-Perry on MSNBC and there’s just this whole class of the Obama-intellectuals who were kind of everywhere, ubiquitous for better or for worse. And then the bottom kind of dropped out of that and it has a lot to do with economic precarity and who’s the first to go, whatever. But you know now we have a wave again because of what is happening, race is happening again, or we’re newly aware of race, that systemic racism hasn’t gone away and I just think it’s a wave that will pass. I would love to be proven wrong. I think there would have to be an overhaul of our imaginations in order to make it something that is sustainable, like a whole overhaul of institutions. Publishing as a whole is broken and I think is set up to attach to trends and performances and then to reward half-baked analysis. The industry also likes to award or appoint one single person, and then find somebody else really quickly, which is what I was talking about in that review. So until we can imagine new institutions or imagine new relationships to institutions, like imagine a whole new thing, a whole new paradigm, I think this is just going to be one of those boom and busts.

IM: Yeah, it seems like part of the problem is that it’s one thing for these institutions to seek out these voices, these different voices, the question is, once they find them, can they actually hear them? Can they understand what it is they’re hearing exactly? Do they even speak the same language?

DAJ: Yeah, and a relationship with a writer is something that to me is cultivated over time. I think the best work comes when a writer and an editor have a relationship where they’re passing books and impressions between each other. I don’t know. I don’t know if it’s set up right now to foster what I think is the best way to create really good work.

HA: Also, I’m often wondering if these institutions are capable of effectively seeking, you know what I mean? Like when you talk about seeking voices, who’s doing the seeking, where are they looking? I say this because I’m not very educated. I didn’t come up in academia at all, you know, my MFA of sorts was coming up through poetry slam, you know what I mean? And so what I see in the way that folks at institutions move to seek out voices, they’re not looking at places like the places I came up as a writer. Or looking at any of the other writers that I’m looking at, like young folks that are doing the work that I’m impressed about but who are not exactly enamored with academia. I think to the people who are seeking are maybe not seeking adequately enough.

IV. “IF YOU FEED INTO THE IDEA OF GENIUS, YOU’RE EFFECTIVELY FEEDING INTO THE IDEA OF SCARCITY.”

IM: Danielle, you spoke about making it clear to Black writers that they can write about whatever they want to write about when you reach out to them, but what do you all think your roles are as editors, as people who are assigning and commissioning work? What is your role in — to the extent to which we can even think about altering these institutions at all, what is your role in that reimagining? I know that’s a big question, but Niela and I think about this too because we are editors. We are seeking out new voices from spaces that maybe these publications don’t normally investigate. I’ve been trying to figure out what my role is, being here in Oakland. How do I seek out new voices of color, how do I make sure those voices are legible to my bosses, and to the reading public? So it’s something I’m thinking through right now as well.

DAJ: Right now for me, I mean I’m thinking through it and I feel like it’s in progress. But I guess I am thinking about how just living in the world authentically as myself as a curious person should feed into the work or what I like, or my taste or what I’m advocating for. For example, like I’m kind of old, so do I listen to what my nieces like and what they’re reading and what they’re obsessively looking at over and over again on YouTube? Am I using that to fuel or teach me about who’s current and who’s relevant? So I guess I want to stay curious and open also, and if I’m doing that with myself then I think I feel more comfortable talking to other people about doing that.

IM: It does feel like sometimes this way in which you have to absent yourself from a conversation. You just become a receptacle for other people’s thinking so you can figure out what’s going on.

DAJ: Yeah, and I think it’s been pretty difficult obviously like we’ve had much reduced human contact, but I didn’t come up writing or analyzing things or wanting to be a writer in a way that was disconnected from how I wanted to be in the world. I want those things to relate to each other. That’s what I hope for. I guess another thing that involves reimagining institutions is thinking about pipelines. What do your interns look like, what does internship compensation look like? I think those are very tangible things that we have a responsibility to try to be advocating for in these institutions. For example, I wouldn’t have ever been able to do an unpaid internship in college or after and so I feel like we shouldn’t have those in the publishing industry anymore. So I think there are very tactical, tangible things like that, that are low hanging fruit. When you just feel really helpless, you can do one thing which is say, “We need to find money for the interns.”

HA: I mentioned the music project I’ve been working on almost a year. It’s called 68 to 05. There’s no point in explaining the whole thing now— it’s kind of a difficult thing to explain I suppose— but in short it is a place that has archival video footage, performance footage, archival magazine covers, and a playlist spanning every year from 1968-2005. But more than that, and more importantly than that, the thing that was most important to me was, when I decided I was going to take this seriously and make it, a big thing for me was I just really want to read people other than me writing about music, you know? As spaces for that shrink, for all writers but particularly for Black writers, for writers of color, to just say “I’m thinking about this album I like and I want to write about it.” You really can’t do that now. I came up at a time, when I had my own blog and people read it, I could write whatever I wanted. I wanted to bring that energy back and put money in people’s pockets to do that and so committing to that project was in a way me saying, “Okay, I’m going to budget out this amount of my own time, this amount of my own money, and I’m going to pay people some money to write about music.” Because that’s what I’m excited about. I still love to write about music myself a great deal, but at some point I felt like a lot of my writing about music is in the world and that’s great and I’m really excited about that, but I really want to read other people. I want to read more people than just me on music. I’m really trying to fight against scarcity. I’m from Ohio where Toni Morrison is from and the one thing that Ms. Morrison did throughout her entire life was to work really hard to fight against the idea of scarcity, and even though most people would call her a genius, she rejected it. Because if you feed into the idea of genius, you’re effectively feeding into the idea of scarcity. That’s a long way of saying, for me 68 to 05 is a thing where I could say, young folks that I’ve worked with in the workshops that are like nineteen but have record collections and want to write about music, you want to write about something? Do it. Pick an album and do it. Someone who is a homie that I’ve kicked it with since I was fourteen who’s not really a writer but fucks with this one album from 1974. You want to write about it? You got it. That kind of thing, not even putting people on but saying, if you are excited about something I want to hear what you want to say about it. Obviously this is a thing where there’s two essays a month on this site so it’s not like I’m reinventing the wheel of music writing, but it was one of those, What can I do? kind of things.

NO: I think what y’all are saying is so important and just giving people reps, giving them the opportunity to find their voice, to work through things, is so important. And as you were saying Danielle, oftentimes the people who are given those opportunities are the folks who can afford to live in New York, it’s the people who can afford to do the unpaid internship at Harper’s. Most of us can’t do that. I started out writing music reviews for Okayplayer and I didn’t get paid anything and my work was not that great— like, I cringe to think what that stuff looks like now— but it gave me an opportunity to test out my voice and to try to edit myself. I feel like those opportunities are dwindling rapidly and the work that everyone here is doing is so important.

V. PASSING BOOKS, PASSING IMPRESSIONS

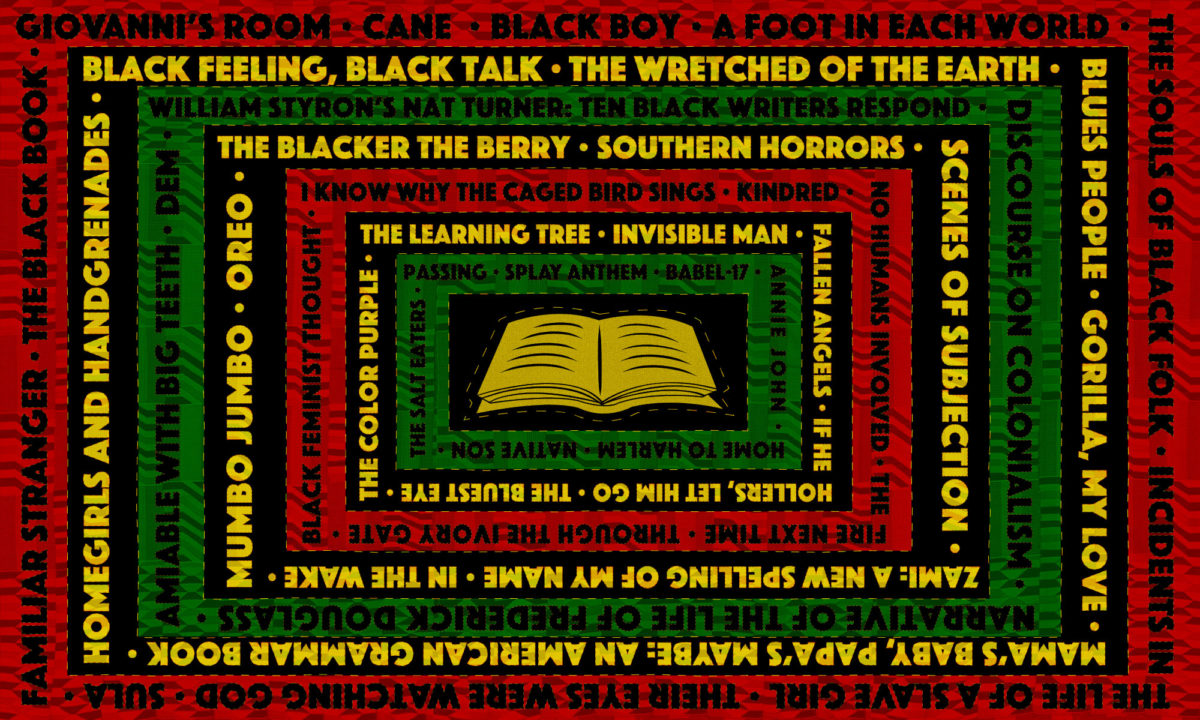

NO: Danielle, you were saying that the relationship between a writer and editor is so special and important and is cultivated by sharing ideas, sharing books. What kind of books are y’all reading right now? What is feeding you intellectually? I guess I’ll start by modeling what I have on my kitchen table, which is my desk. I’m reading William Styron’s Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond. I wrote an essay about this book in college and I’m finding it to be very important now, and I’m also reading a collection of columns by the Chicago writer Leanita McClain. She passed away in the ‘80s but she was an incredible writer and reporter and I feel like her work has been largely forgotten.

DAJ: Is that A Foot in Each World?

NO: Yes!

DAJ: Are you gonna write about that?

NO: I would like to. There’s a lot that I’m circling right now. Ismail knows this, but I’ve been trying to write about Gayl Jones in a way that’s respectful of her situation. I’ve been thinking about her as an elder, especially during a pandemic, and as someone who is cloistered and potentially isolated. I’m wondering who is there for Gayl Jones. Who is checking in on her? I’m getting chills thinking about her being alone. But anyway, those are the two things I’m reading right now. What are y’all reading?

DAJ: I’ll go. I’ve been reading Emily Lordi’s new book, The Meaning of Soul. I started it a little bit before the pandemic and I’m kind of rereading it now because she talks a lot about soul logic and the inherent resilience of the tradition of soul music in this continuum of music that comes from gospel, and I find it to be a super helpful way of thinking about how to listen to music. My favorite kind of music criticism, or any kind criticism, has this sense of, “Hey, I’m going to take you along with me while I explore something and learn about it and we’re going to learn about it together.” And I think she has such a way of modeling that which I really love. Also, I grew up in Memphis and I lived in New York for a little over fifteen years and I just moved to Little Rock, which is an hour and half outside of Memphis. Inspired by all of this movement, I’ve been reading a lot of collections and stories—most of them written by Black people—about place, like the places in which the authors live or were born. So I was able to have an interview with Minnijean Brown-Trickey who’s one of the Little Rock Nine last week, and that was probably one of the most awesome things that’s ever happened to me in my life. So I read several histories and accounts of the Little Rock Nine school integration crisis here. I’ve also been reading Bryan Washington’s essays on Houston. He has something forthcoming for us that I’m excited about. And I’m rereading Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts on Harlem; a biography of Curtis Mayfield, so it’s a lot about Chicago and the era in which my mom was born; and a biography of Henry Dumas, who is from Sweet Home Arkansas, outside Little Rock.

NO: I feel like Toni Morrison is a through line through so many different conversations, but Dumas’s work is so emblematic of the work she did as an editor. I’m thinking about Ark of Bones, Dumas’s first collection of short stories, and how that book might not have been available to us without her efforts.

DAJ: Not at all. Gayl Jones, also. I just read Eva’s Man and that was a lot. It was wonderful. It’s something; I would like to read Gayl Jones with people.

IM: We should get a reading group going.

NO: Yes! I would love to know what y’all think about White Rat. Have y’all ever read that short story collection? It’s amazing. She’s brilliant obviously, don’t want to use the term genius, right, or maybe I just want to problematize it. I hope she’s okay. Cassie, what are you reading?

CO: I’m reading The Philadelphia Negro, finally. I took a break to finish reading Vibration Cooking but yeah, I’m back to it.

IM: How are you finding it right now?

CO: I basically feel like I go through extremes reading it. I’ll be thinking in my head, “Wow, this sentence is perfect. Is Du Bois like the best academic writer ever?” And then I’ll turn the page and I’ll just be thinking like, “Yo, this is really classist as fuck and nobody told me.”

NO: Have you read Saidiya Hartman’s new book?

CO: No.

DAJ: That’s something else to read with people! That Du Bois chapter is juicy. It’s great and rigorous but it was also juicy, like I couldn’t put it down. It has some narrative drive and tea kind of stuff in it about Du Bois that I appreciated. [laughs]

NO: Yeah, I appreciate the ways that it demands that Black professional artists consider how they look at and relate to other Black people who aren’t professional artists, you know what I mean? Hanif, what are you reading right now?

HA: I just want to say, I love Emily Lordi’s new book, and Emily Lordi is someone who I turn to to think about how to write about music generously. But the main and only thing I’m reading is the new collection of Wanda Coleman’s selected poems, the one that Terrance [Hayes] edited, and thinking a lot about how good it feels. For me, Wanda Coleman is someone who, no matter how much she gets in terms of roses now it’s never gonna be enough. But it has really been good to see contemporary poets, particularly contemporary Black poets, re-recognize and re-celebrate Wanda Coleman in the past couple years, so I’m reading those selected poems in celebration of that.

NO: Ismail, what are you reading?

IM: I’m still working my way through Nikky Finney’s new book, Love Child’s Hot Bed. It’s incredible. Talk about community — it’s a book that’s rooted in this sense of artistic production that comes from a specific place and specific kind of people and it’s been giving me a lot of hope over the last month. Wanda Coleman actually — I have to create these mood boards for myself as I work on my novel, which is about Black Los Angeles, and Coleman is one of those writers who keeps me in the right headspace for that. And then Jean Genet’s Prisoner of Love. It’s like his travel log about moving through Palestinian refugee camps in the ‘70s, and again it’s a book about place and it’s different because he’s an outside observer and it can be weirdly anthropological sometimes, but he writes about Palestinians and their struggle and its loving and nurturing in a way that I’ve needed right now.

VI. JOY

NO: Right before you all got on the call, Ismail and I were talking about how excited we were, and that both of us were so nervous to converse with y’all because it feels like this is more important than other things that we’ve been doing recently. We just have palpable enthusiasm to be able to talk to other Black writers and thinkers. I don’t know, it just feels like the first day of school to me. [laughs] Thank y’all for being here.

What’s bringing you joy right now? I think it’s important to consider joy as we’re also thinking about trauma and crisis. I can start. I am again getting a lot of joy from The Parkers. I’m getting joy from walking around my neighborhood when I can. I’m finishing up an essay about seasonal language and the ways that we name periods of change and I ended up incorporating but ultimately cutting a reference to Lil Wayne’s “Dough Is What I Got” freestyle. Y’all remember that? From 2007? It was the passing of the torch between him and Jay-Z. And so for the past two days I’ve just been listening to “Dough Is What I Got” on repeat. I think I was telling Ismail the other day, or yesterday, that I’m also getting joy out of The Shade Room and the way that that website is extremely caustic and problematic and so messed up, but like, it’s also entertaining. They tried to change their tone to address what’s been happening in the world but they have slowly gone back to what they usually do, which is like, “The mother of Future’s child wants $53,000 a month in child support!” [laughs] He’s trying to give her $1,000 a month. But anyway, I’ve found joy in the stupid little gossip stuff. It’s been really fun and distracting and it’s something I read just to turn my brain off.

IM: Did you see it this morning Niela?

NO: No, what happened?

IM: They’ve fused the social activist stuff with the trashy stuff in a really good way. I’ll send it to you.

NO: Okay! [laughs]

DAJ: For me, it’s similar. It’s like intergenerational conversations about little trifles that are somewhat gossipy. So I’ve been gossiping with my mom about things that my sister-in-law is doing that make her laugh, or kind of annoyed. I think she wakes up in the morning and she’s been stir-crazed or something and she’s doing video diaries on Facebook every morning at 5am. So my mom likes to call me and say, “Today she said..” whatever, whatever, whatever. So, playfully making fun of people. We would also do this to her face, so it’s not that caustic. And then, I guess like, group texts with my girlfriends in which we can make fun of men in similar ways. That’s helpful and funny. Listening to my niece brings me joy. She’s sixteen and she got a new job, her first job actually, at Texas Roadhouse Grill, so just hearing about how her days go is exciting for me. Oh, and Dating Around. You guys should watch the second season if you haven’t, if you have time.

HA: It’s funny that Lil Wayne was mentioned. This brought me joy in a weird way: Something compelled me to go back to listen to the last Lil Wayne album and it was as bad as it was when I first heard it and I had this weird crisis where I was like, “Was Lil Wayne ever good?” His run, like the run where he was really efficient, effective, and skilled is kind of small compared to other “best rapper alive” eras. And so I had this thing where I was like, “Man, maybe I imagined that. Maybe we all imagined that. Maybe we were all tricked.” But at the beginning of this week, I went back and listened to No Ceilings, the mixtape, and was really happy. Listening to that tape confirmed [his skill]. I don’t know. I’m thinking about this because Lil Wayne was once like very very good, like almost floating.

A thing that’s bringing me joy. I don’t have a lot of time for video games anymore, and haven’t for years, but I started playing The Last of Us [Part] II which is this survival zombie type game that relies a lot on silence and jumpy movements and having to crawl through grass to not be detected. I mean, I’m an anxious person but it ignites a really palpable anxiety where I can only play for like twenty minutes at a time before I have to set it down. There’s something celebratory for me about not being made anxious at the hands of the state or an institution. It’s just funny and somewhat thrilling to be made anxious by CGI zombies and small noises and that has been joy-bringing.

CO: I’ve been getting a lot of joy watching stand-up on YouTube and Netflix. Before the pandemic I didn’t know about Yamaneika Saunders but she’s dope. She’s hilarious, and so I’ve just been watching basically everything that I can by her. And of course people like Jaboukie [Young-White]. I watched Dave Chappelle’s special most recently, but that didn’t feel like stand-up to me. That felt like a conversation he had with his neighbors about race. So, yeah. But in addition to that, something that I also watch for joy are ballroom clips. I was working on a project on Philadelphia’s ballroom scene that came out in December and I’ve been working with the community to do more stuff moving forward. I have just been learning more about ballroom and also getting my life watching clips on Youtube.

IM: I guess for me it’s the same as it was earlier this year, just walking a lot. I feel really appreciative of being in California at this time. I like having a backyard, and walking through my neighborhood and enjoying the pastel painted houses, although that is fraught in its own way. I live in North Oakland so things are always kind of on the edge of fully gentrifying but it brings me so much pleasure. Also, my plants. I just recently got into taking care of plants, so having these living things to look after every day, like remembering to water them and prune them and feed them is really great. HBO Max brings me a lot of joy right now.

NO: Yeah, thank God for HBO Max. I binged Insecure a couple weeks ago and I just love the music and the cinematography and the topography of that show. It’s gorgeous. But anyway, thank y’all so much for talking with us. We really appreciate it.

IM: I just wanted to thank you guys again for this conversation. This went even better than I could’ve imagined. It’s really been scintillating for me.