“And it was then that fear, and with fear serious reflection, began.”

—Albert Camus,The Plague

What have you done as COVID-19 spread—first slowly, and then very, very fast—across the United States, shutting down theatres and professional sports leagues, businesses and schools and universities, driving us into our homes? I’ve turned, as is my tendency, to books. My wife and I had already laid in stores (“I went and bought two Sacks of Meal,” notes Daniel Defoe in A Journal of the Plague Year, “… also I bought Malt, and brew’d as much beer as all the Casks I had would hold,”) and shut down all but the most essential face-to-face encounters. Time loomed before us, like it always does, as a question mark. “There was a serene blue sky flooded with golden light each morning,” Albert Camus observes in his novel The Plague, “with sometimes a drone of planes in the rising heat—all seemed well with the world. And yet within four days the fever had made four startling strides: sixteen deaths, twenty-four, twenty-eight, and thirty-two.”

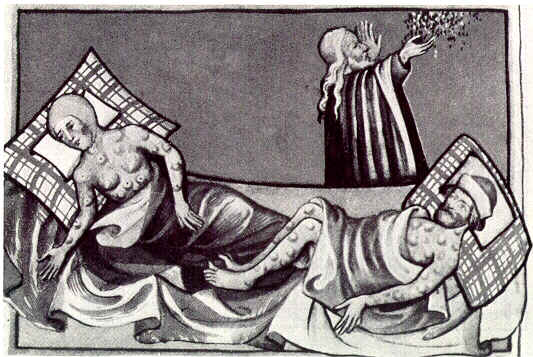

The Plague was Camus’ second novel, published in 1947, not long after the end of the Second World War. It has long been considered an allegory referring to the Nazi occupation of France (as well as the ensuing French Resistance), yet while I don’t dispute that, it is not what I am looking for. What interests me, instead, is the experience of reading the novel in the midst of an equivalent situation, as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds. The Plague is just a single example; the literature of pestilence, of contagion, is rich, going back hundreds, if not thousands, of years. I think of Boccaccio’s Decameron, composed in the 1350s, a confluence of stories shared by ten young people who flee Florence during the Black Death epidemic of 1348 and isolate themselves in a villa outside the city for two weeks. I think of John Edgar Wideman’s The Cattle Killing, with its core narrative about the 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic in Philadelphia: “[c]ircles within circles,” Wideman writes. “Expanding and contracting at once.” I think of A Journal of the Plague Year, an account of the 1665-1666 London plague that killed 100,000. Defoe survived that epidemic as a child—he was born in 1660—although his book, published in 1722, is fiction as opposed to autobiography. What this suggests is that, even if art cannot ultimately save us, our humanity depends on its expression just the same.

Something similar might be said about The Plague, which Camus began writing in the early 1940s, before the outcome of the war was clear....

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in