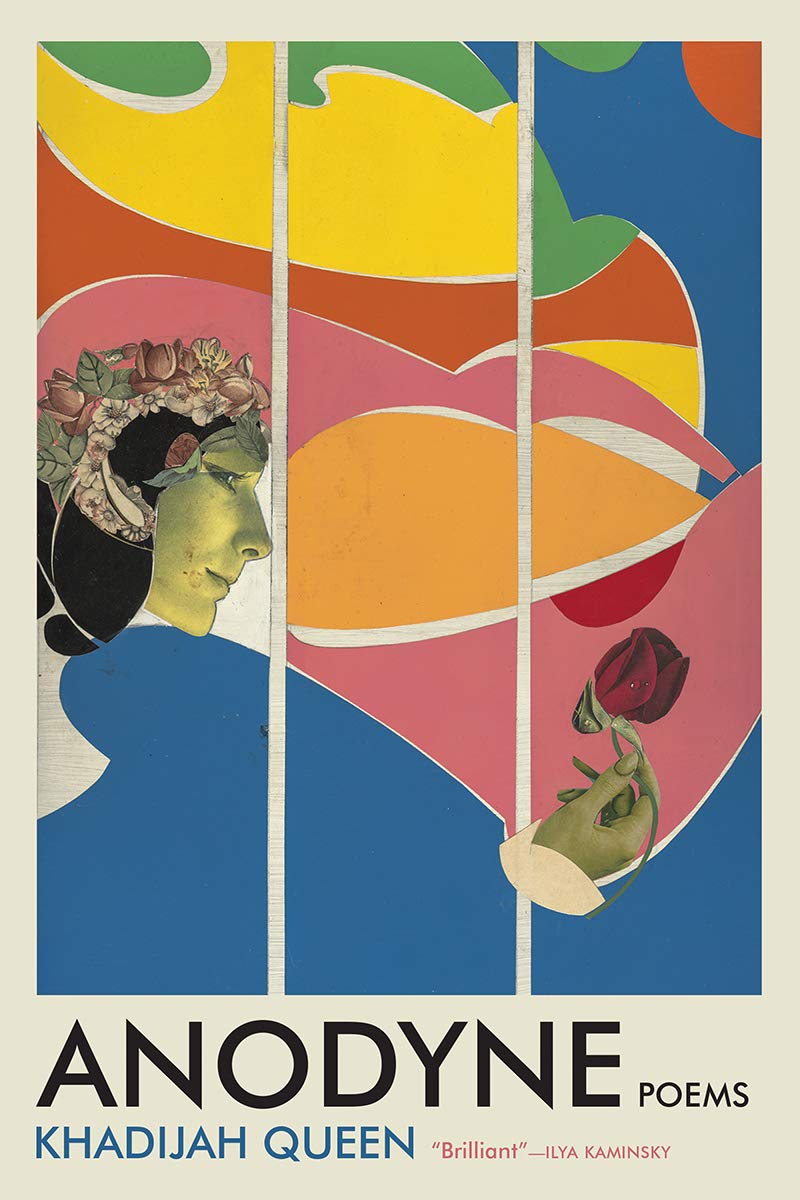

Khadijah Queen’s newest poetry collection, Anodyne, is an eerily prophetic treasury of forms and methods for departure and conjure, even when and where no apparent movement seems possible. It is a book, in a way, about the fine art of movement and maternal modes of bringing forth, between a rock and a hard place—without literally, or “only” being about motherhood, about care, about love. By turns spare and voluble, lines cut as though with a scalpel or emerging into consciousness like incontrovertible mist, the poems in Anodyne are anything but, dealing with and doing pain while moving, line by line, toward a future I feel in the alreadiness of my brightest prayers.

I read the book three times, then wrote Khadijah some questions, and then, on a hot night, we Zoomed. Reader, we want you to know that this conversation came to over twenty transcribed pages—which is to say, it has been significantly expurgated. We wish we could give you every last word. But we can give you this.

—Ariana Reines

ARIANA REINES: Do you want to talk about men and how marginal they are? [Laughter] In real life and in your gorgeous book? Do you want to talk about blood and the womb and motherhood? Let me phrase this as a better all over question, applying to the entire collection:

Motherhood isn’t just a subject of many of the poems in Anodyne—I feel it is a tone. I feel the speaker is often mothering the poem, and also herself. There is a way in which I feel these poems were raised as well as written, and this strikes me as an ethics for composition—a form of justice I discovered by reading your book.

“A good mother does what it takes.”

KHADIJAH QUEEN: I LOVE THIS SO MUCH. Motherhood as a tone—the character of it, a movement through and underneath the sounds, how it harmonizes the content. Yes. If motherhood is the dominant force of this book, that reflects its dominance in my life generally. Sometimes people say “How do you do it?”—talking about solo motherhood, raising a Black man in America right now, or ever. And that’s not what exhausts me. It’s the weight of false expectation, the constant vigilance it requires, the circumstances imposed from outside our little family cocoon, which we honestly delight in—my son and I have always enjoyed each other’s company and known when to give each other space. Another book to write about that.

But you asked about self-care. I did have to learn how to take care of myself, real care, as I was writing the poems in this book. In September 2016, I quit a job that was destroying me physically. I threw off family pressure to take a traditional path and made my own. Earlier in the year I endured a deep trauma that was somewhat public, somewhat not—another book there. Speaking of men. They are indeed marginal here, though they sure did try not to be. Then there was the election, and being a full-time PhD student. And my son was approaching adulthood in this climate of violence against people who look like him, and I don’t want to speak for him—just as a mother wanting to shield him and teach him how to live, in a world that steadily presents him with death as a common thing, the expected horror of it—it felt impossible at times. Impossible. Yet we continue.

AR: “I slept in the palm of my own black hand,”—just knocked me on my ass, took my breath away. The entire poem—the final poem. It is haunting, invigorating, and IT moves—it makes me think of the anaphoras of Amiri Baraka and Inger Christensen’s Alphabet, but it also makes me think of the way writing can build a moving vehicle out of stasis. It also unwhitewashes Leadbelly’s famous lines, and seems to answer the jealousy and possessiveness and inadequacy of…. all men?

And the refrain, “I slept when I couldn’t move,”—I think it’s the refrain I want to ask you about. I want to hear anything you might be willing to say about this refrain. I feel its meaning in my body as music.

“I slept in a system outside of every law but one

I slept when I couldn’t move”

By God. I want to know how you came to write this poem, how it came to you—

KQ: Everyone will hate this answer, but…I wrote it in a workshop. It came from an exercise that Eleni Sikelianos, who is kind of a magician of writing exercises and from whom I learned a lot, gave us as we read/discussed Alice Notley’s über-haunted book In the Pines. I can’t remember if she played the song for us in class. I think she did. But I had already listened as I read Notley; the song was my way into the text. And when I saw that the original title was “Black Girl (In the Pines),” and how Black got changed to “My” sometimes, then “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” that erasure of the very first lyric he sang, and the sadness of the song addressed to Black Girl, said in such a familial/familiar tone to me, I kind of imagined myself among those blues, in those lyrics, the height of them, thinking of how my mother said her father never talked about Georgia except to say he didn’t miss anything about it but the pines. And it’s a murder ballad, one that I took at first to be about lynching rather than a domestic violence issue, and which still feels more right to me. Which brings me back to the haunting we talked about in Notley’s book that I really resisted because I was/am haunted enough.

AR: I want to talk about blood and fibromyalgia, but only if you want to.

KQ: There is no scientifically known cure or cause for fibromyalgia. I know what I know because I live with it and because I’ve sought out more successful (compassionate, effective, dependable) treatment outside of our healthcare system, which I could write a whole ‘nother book about but not today. To be brief, to live every day with chronic pain and fatigue for twenty-plus years means that my awareness of my own body and energy is acute; fibromyalgia is also a hypersensitivity to pain and sensation. There are things I can say about diet and blood type, blood and inheritance, blood in the tiny cuts on my hands from constant pandemic handwashing, blood and inheritances, spillage—too much, never enough it seems. “I slept when I couldn’t move” calls out the action of exhaustion and the state of it, what can and can’t be helped in terms of energy and circumstance. Every now and then, when I do too much, my body just shuts down, refuses movement, imposes pain as enforced stillness. That happened not long before I wrote this poem. “Black Girl (In the Pines)” also made me think about life and death, its circumstances for Black women in particular, the endless labor, the constant precarity. And it took two years for them to figure out my fibromyalgia diagnosis—I didn’t know what was wrong all that time, but I knew something was. I trusted myself, despite them trying to tell me it was in my head—and yes, it is, but studies now show it has something to do with how the brain process pain—and in the meantime I thought either the pain or the aggressive lack of diagnosis might fucking kill me. So all of that swirled into the making of that poem, even though, yes, activated by a writing prompt.

AR: I want to ask—what would the future your book sees its way to look like if we measured our ethics against what a good mother does and would do. I want to ask, what is the meaning of a good mother to you, and what does it take to be one (while I hear this refrain, Everything, Everything, revolving in my own brains)—I want to ask…

KQ: I suspect that we would look more like New Zealand right now and in the future, rather than this disastrous nightmare in which suffering is more acceptable than care, where death is chosen over life yet death-dealers claim the opposite, and generosity toward oneself is considered a reward for hard work—yet the hardest workers go unprotected, unfairly compensated. It doesn’t take much to be a good mother, and yet it takes more than everything you have. You have to pay attention to and meet the needs of another person or persons while attempting to meet your own. That’s the trick. Sometimes you succeed, sometimes you don’t. You try again every day. You ask for help. You make mistakes. You apologize and try again. If a good mother shaped the world with all the power of her intention, we’d all have the resources to go about meeting those needs, apologizing for fuckups, trying again. We say we want the best for our children; when we want the best for each other as well as ourselves, we might reach another level of human evolution.

AR: And the title poem. I just stopped myself from typing the whole thing back to you. I too wish I’d learned to take better care. Which I read as both to do it myself and to receive it better—I wish I’d learned that. I had to look up the root definition of anodyne. “Without pain.”

The title of the book feels almost ironic—because of the way the word is used in ordinary speech to denote something without volatility or without danger—which I would not say your book is—but I want to ask you about healing.

KQ: Oh, definitely ironic. I don’t often imagine what it would feel like to live without pain. Every now and then, a handful of fleeting hours through the years, I do get the surprise of relief, and I have to be careful not to fill it with doing that puts me right back into the pain routine with a vengeance. But beyond my personal shit, the word anodyne seemed like this prescription for being, when I saw another definition: without offense. Deliberately aspiring to inoffensiveness, like we should aspire to the anodyne, go along to get along, humping after objectivity. But no. That kind of unquestioning foolishness is how we got into the morass we’re in now. With a nod to Sara Ahmed’s On Complaint and Living a Feminist Life, we have to evolve past calling the person a problem while ignoring the problem they point out. Our lives depend on breaking that gaslighting-adjacent habit.

It took me a long time to remember to be offensive if I had to be. I was a bold little girl, outspoken, not a humble Muslim like I was supposed to be, at all. But after so much trauma—it makes you quiet, terrified, unsure. Any one of the countless things I could say out loud would be enough to make anyone fall apart, and I have. I kept going anyway, and there is something pain-relieving about that continued survival—not physically, but emotionally—especially when paired with care. So, to tell another of the book’s secrets outright, knowledge of that is a kind of pain-relieving medicine.

AR: And about one of the many techniques and forms the book employs to amazing effect—erasure. I found myself thinking of the wound healing in Wanda Coleman’s MERCUROCHROME—

KQ: I literally bought that book and read it in one sitting right before the first time I revised ANODYNE all the way through—

AR: No shit! Well, I felt her spirit near as I read you. If you want to, will you tell us about a book without pain? About a pleasure without pain, about a single perception, a single syllable—without it. Because the more I read it the more I realize—

“folding screams into lace”

—that even the seemingly subtlest most quiet lines in your book are charged with haunting fury….

“What else can we do

for protection?” I think about that in the ecstasy

of a sweet peach & irony of death & theft of indigenous

and & the violence of language in every space

I enter & I think I am losing everything but my mind.

I certainly am paying for the trouble,”

The way dread and history are inescapably part of the pleasure and savor of friendship, the brief respite from white supremacy that friendship protects, provides—a peach, dessert—no pleasure tasteable without the “irony” of everything that pleasure isn’t– I feel this acutely and one of the things I love about the poems in this collection is they do not merely stay upon, dwell upon, or fetishize either suffering or joy—they are always poems of motion. Ranging in tone from elegaic to indignant to resplendent, centering and de-centering the lyric I… I think one of the motifs I feel moves thru the entire collection is actually motion itself. Can that be? Is that right?

KQ: Yes, this is right. I feel like I don’t even have to answer—I can savor the gift of this reading, and feel joy knowing that the work communicated so clearly, and hope that other people generous enough to choose to read this book will trust their instincts, too, that the poems have trusted them to answer their own questions and find a new respect for their own minds, hearts, instincts.

AR: What does motion mean for you. What kind of a relationship do your poems have to your sense of liberty, liberation, repair, reparations. Please answer as wildly or precisely as you wish.

KQ: As an artist, I feel at home in motion. Mentally, physically. I have to have freedom, to be free within myself without interference, free to go somewhere when I choose—in space, in inquiry—or to remain in a place, with a subject, according to my energy and curiosity. I like the practice of choosing a direction, an approach, a medium, a structure—construction in motion might describe how I make. Intention in the saying and in the planning, certainly, but infinite freedom to adjust with the arc of my imagination, even within the constraint of page or poem or language or book or body, and in whatever body you have, the vibrating motion of existence, articulating that loving and difficult and complicated and gorgeous experience of being alive.

But also: I’m not free unless everybody’s free. I don’t know that there’s another place to explore that with the same type of immediacy and ease of access than poetry. There might be visual art, performance art, or music. But to me, poetry allows you to be both immediate and long term.

AR: Yes. It exists in the x- and y- axes of temporality.

KQ: Yes.

AR: So right. The myth of normalcy. I love how you combine that with fucked up ideas about women. To me, I wasn’t alive— at least not in this incarnation—earlier, so I can’t comment. But I feel like the 90s were putting forth this idea of normalcy in a really hardcore way with an extremely fucked up situation with women. That was my youth and adolescence. That’s when I got embossed into that particular matrix. You said, “enraged and disappointed,” which describes perfectly my state. The disappointment, the weariness, and the exhaustion feel maternal.

KQ: Because it’s endless. We can’t see the other side of it because it’s still happening. Whereas with some other circumstance it was like, “Okay, this is temporary and we’ll get past it.” I even just said that to the class I was teaching before this. Teaching online because we won’t be doing it forever, we hope [laughter]. We don’t know how long we’re going to be doing it, though. And we don’t know just how horrible the consequences of this administration’s behavior will be. They’re already past the point of tolerance. They’re still here. I feel like I don’t know. And when you are uncertain, especially as a parent, it puts you in a state of constant fear and agitation that is exhausting, and then you just rotate along that. So what you do to continue is the routine stuff. For poets, that’s returning to language. As a person, it could just be trying to feed yourself and get enough sleep and checking in on people that you love. And, I don’t know, watching your favorite terrible show.

AR: Can I read the first poem back to you?

KQ: Yes!

AR: Because it’s RIGHT NOW.

In the Event of an Apocalypse, Be Ready to Die

But do also remember galleries, gardens,

herbaria. Repositories of beauty now

ruin to find exquisite—

the untidy, untended loveliness of the forsaken,

of dirt-studded & mold-streaked

treasures that no longer belong to anyone

alive, overrunning

& overflowingly unkempt monuments to

the disappeared. Chronicle the heroes & mothers,

artisans who went to the end of the line,

protectors & cowards. Remember

when pain was not to be seen or looked at,

but institutionalized. Invisible, unspoken,

transformed but not really transformed. Covered up

with made-up valor or resilience. Some

people are not worth saving, no one wants

to say, but they say it in judgment. They say it

in looking away. They say it in staying safe in a lane

created by someone afraid of losing ground,

thinking—I doubt we’re much to look at,

as we swallow what has to hurt until we can sing

sharp as blades. Aiming for the sensational

as we settle for the ordinary, avoiding

evidence of suffering at all costs, & reach

clone-like into the ground as aspen roots, or slide

feet first down a soft slope, wet, cold—but the faith

to fall toward the unseen, against the bleak of most

memory, call it elusive. Call it the fantasy to end

all fantasies, a waiting fatality, the wreck of both

education & habit. Warned inert,

we could watch ourselves, foolish, lose it all.

That’s a whole book, that poem. All the hair on my body is standing up. It’s existing on those two axes of time we were talking about. It’s the exact diagnosis of the present, but it also radiates back in time. It speaks very precisely to the past and to the present and there’s a science fiction-y quality about the future here. Or am I wrong?

KQ: You are not wrong at all. Thank you for that. That was beautiful. I feel like that poem is one of those that arrived. I changed a few little things, but it is mostly how it arrived. The ending I played with a little bit. It was actually harsher. I wrote it when I was teaching Octavia Butler. I had gone to a reading right after the election—ZZ Packer’s short stories. I had brought my big blanket coat because it was December or something and I was just sitting in the chair listening to her read and I was like, I want to stay right here until 2020 [Laughter]

AR: And so you did. You found a way to. I think some very science fiction-y things are happening.

KQ: I do, too.

AR: Not only are we remembering somebody else’s stuff— which is what museums, archives, galleries used to be a pleasure for— but our own lives are like that now.

KQ: Yes. And we’re watching ourselves lose it all.

AR: We are.

KQ: And what are we doing about it?

AR: We don’t know what to do. Yeah, I want to start crying.

KQ: I know. If you sit with it it’s too devastating. I think that’s why I have that line in “Erosion”: “how we fail is how we continue.”

AR: Yeah.

KQ: You were talking about motherhood being a tone. There’s this culture around motherhood of doing everything perfectly right— enrolling your children in the right school, making sure they’re wearing the right clothes, studying the right thing. I just found it all so absurd because there were so many times I messed up, and yet my kid is still a delightful person. All of my friends love him. Anyone who meets him, who’s a good person, loves him immediately. I joke with him that everybody likes him more than me because he’s just a magnificent human being [Laughter]. At my best, I got out of the way so that he could be that. I moved other shit out of the way so he could be that. Not that I did everything fucking perfectly because who does everything perfectly and what does it cost you if you do?

AR: I don’t think it exists.

KQ: It’s a fucking crock of shit.

AR: It’s a total crock of shit.

KQ: I don’t know what that had to do with your question [Laughter].

AR: A lot! The tone… I think that’s something. I don’t have a child yet. I don’t know how to talk about that.

KQ: Well see, that’s another thing. We have to not police other people’s existence.

AR: No shit.

KQ: Oh my fucking god. If somebody doesn’t want to have a kid then they don’t want to have a kid!

AR: Well, I don’t know if I don’t want to have one.

KQ: And if they don’t know, that’s fine.

AR: But it’s like, I have my feelings about it, right?

KQ: Mm hm.

AR: And my feelings about it change. But I feel like there’s a fetish of the mother, her care, and her worry. That’s not what I mean by “the tone,” though.

KQ: Because that’s not what it actually is. That’s the surface depiction of it. Motherhood is hardcore. It’s the hardest thing you’ll ever do and it’s not valued, which makes it harder. They give you lip service and a day of flowers, but are they going to help you with childcare? Are they going to help you with housing? Are they going to make the schools safe to attend? That’s how you show that you value mothers. Not because you gave them a box of something shiny on Mother’s Day.

AR: Seriously. Or because you are going to make a fetish of their generosity.

KQ: Right. Or martyrdom.

AR: Exactly. I feel like there’s a way that the poems are giving to live and letting to live themselves and what comes through them. My sense that one of the organizing structures of the book is motion is really interesting. Like you said when we were both on the brink of tears just from the first fucking poem, “If you sit with it too long, you can’t.” You’ll explode. You gotta go, you gotta move. I love the way this book moves through forms, moves through tones and modes and spaces and places. It gets funny and exalting and devastating, but it stays moving.

KQ: That’s how you stay alive.

AR: It is how you stay alive. I notice that a lot of people I admire and consider very smart kept calling it and you “resilient.” I agree, but I am so triggered by that word [Laughter].

KQ: Right. That’s why I put that in that first poem, “Made-up valor or resilience.” I don’t want to be resilient. When you live in a body that is under attack, you don’t want to be congratulated for resilience. You would rather somebody recognize how fucked up it is. It’s not that the work is good or that you are good or great or beautiful or whatever because of that resilience, but despite it. Because resilience is costly.

AR: Resilience is costly.

KQ: And precarious.

AR: So precarious. And I could take this little jalopy called “resilience” and put it on a different track, which is that poetry is a means of survival. It’s not a matter of those galleries and trinkets. It’s something much deeper in the bone and in the guts than those kinds of art. I feel like we’re in a moment right now as the outer world collapses and implodes, where people are like, “Oh, what architecture have you got?” And there’s a lot of architecture, also, in this book.

KQ: I just can’t even get over how amazingly your vision is employed in asking these questions.

You’re amazing, I just want to say that, by the way. Your name was literally the first one that popped into my head and I didn’t give them any other options [Laughter]. I was so happy when you said yes. Thank you for those incredible questions.

AR: That means so much to me. Thank you. I was really honored and delighted. One of the things I fantasize about this conversation doing is to show love. I want to show up by giving love. That’s one of my ambitions for what this will become. It will become three minutes in somebody’s life on their phone in a month or two. I just feel like that hasn’t been modeled enough. I can’t hear it and see it enough.

KQ: I agree.

AR: I read and I write because I’m hungry and I’m starving and my soul needs to live. That’s what I do. That’s what I do this for. I get irritated because it turns into something else. Everything about this world is a deforming and confusing situation, it often seems. And yet, we have this access to the absolute and we do what we can with that access. So I will try my best. I do get it wrong, but I do try. So what I could say about resilience is that, well, if you want to have any, poetry is a good idea. If you intend to survive or even do better than survive in this completely bullshit situation, poetry would be a good idea.

KQ: Yes, that’s right. Your wellbeing depends upon the clarity, sharpness, and accuracy that poetry contains. If you don’t have that, you’re susceptible to these shaping forces that are not generative, not suppressive, but simply refuse your humanity.

AR: They do. They kill.

KQ: So you become a shell of a human. Not fully human and not fully embracing who you are as a human being. You’re missing some pieces of not only what’s possible, but also what is in denial of it.

AR: That’s so utterly true. I think that the practice of poetry has taught me how to notice when I’m doing that to myself, which is more often than I would prefer to admit.

KQ: Yeah. It took me a long time. I am 45-years-old. I feel like I couldn’t access that fully until I was past 40. But it sure is nice now.

AR: You feel like you can access it without interruption?

KQ: It feels instinctual. There are still moments where I’m like, “That was fucked up and I didn’t say anything.” But more often than not, I recognize it instantaneously and I’m able to address it and say no.

AR: Both within yourself and in situations when you’re dealing with bullshit from people?

KQ: Absolutely. It’s great.

AR: It is great.

KQ: Can’t say I would have done it without poetry, though. Or Toni Morrison.

AR: Yeah. Toni Morrison could teach an alien how to be a person a hundred billion years from now [Laughter]. I think her work is a total soul school. It’s a treasure.

KQ: I know a lot of people call it difficult, but it’s just so crystal fucking clear. Like, why is clarity difficult? Why is truth difficult? I will never understand that. I don’t like tiptoeing around shit. I don’t like objectivity. Fuck objectivity. Where’s the passion behind it? You will find the clarity there. In Lucretius’ The Nature of Things there is this admonition to be moderate, not passionate. I think it’s because many people who are unevolved use anger and negative feeling—non-generative/destructive feeling—to rule their behavior, versus what you notice in Anodyne in terms of motherhood as a tone, which is generative and constructive. So if we can articulate our feelings without harming other people physically, we are closer to being human. And we’re not putting on this artifice of objectivity or being the middle. Fuck neutrality. That’s why we’re in the shit we’re in now.

AR: So true. Will you say more about neutrality, please?

KQ: Well, I just don’t understand the pretense. You know you have a feeling. And if you don’t, well, how terrifying is it to not have a feeling about something? I don’t mean it in a way that says anything about folks who are neurodiverse, where they feel neutral towards something. I’m talking about neutrality in terms of an action required for survival, someone else’s care or wellbeing, or the state of the world. Those kinds of things. Not whether you feel positive, negative, or neutral about somebody’s house décor, for example. I’m talking about things that really matter to life and death survival. It’s like in a debate. You can’t be neutral about children in cages at the border. That’s a crock of shit.

AR: I want to introduce the word “complicity” into our dialogue. For me, one of the weirdest experiences of my every single second is the experience of total complicity and the way that I experience that somatically. I work really hard not to overwrite how that affects me somatically because that makes me an accessory to the problem. It actually defangs or declaws my capacity to speak with that lucidity that you were talking about earlier. But it eats at me because that complicity bothers me. It bothers me. I don’t live well with my complicity. As a Jew, with the trauma I carry, I don’t live well, can’t live well, inside the whiteness to which I’m complicit. And I feel like we sell, in America, a kind of ease with oneself as the ultimate prize of success—whether it’s a New Age prize or a capitalist prize or the prize of having achieved some kind of transcendent love. I have come to cherish my existence, but I just can’t swallow America, and I never have.

KQ: It’s impossible to live with it. The only thing I feel that can be done is to transmute it into action and to keep doing it. Making action a habit. Whatever you are capable of doing. In 2011, I went to this panel called “Native Innovation” at Poets House in New York. I never forgot it because I asked Joy Harjo what she did with the anger. The panel talked about all kinds of unconscionable harm done to Indigenous people. I said, “What do you do with the anger?” And she said, “You have to transmute it because it will harm you and not whoever who’s harming you.”

AR: That’s so exact. That’s so right. It’s a daily alchemy. Joy Harjo is also one of the most joyous poets that we have.

KQ: I love her work. I teach it all the time.

AR: Me, too. It’s so healing. Her work is so healing. But that’s another word that triggers me! But her poems ARE healing!

KQ: I know, right [Laughter]. It’s because it’s a process. It’s not like you’re healed and it’s over!

AR: It really is magic, though! You can be all messed up and a poem can fix you. I’m here in the hospital of literature. I came here cos I was desperate to heal, to change, to get some kind of insight—anything.

KQ: Same. I had a lot of housing insecurity growing up. There were times when I lived with my dad who had a lot of money and we were doing okay, but my mom sometimes didn’t have much and I found security, stability, escape, and a place for my imagination to live freely in literature. Wherever we were, there was a library. I lived in the library. L.A. Public Library, shoutout, thank you.

AR: I love the LA Public Library [Laughter]. I wrote a book in the L.A. Public Library.

KQ: We don’t overstate how much it means to us that we got to participate in imagining with all of these authors and the worlds that they made. Can’t overstate that.

AR: It’s a total refuge. I also want to come back to this idea of freedom. I have brought up three very triggering words.

KQ: Yes. Freedom, healing, and resilience.

AR: It sounds like a TED talk! Add “motherhood” and it’s a GOOP podcast [Laughter]. I don’t know what freedom is, but I know that I always felt the poets knew something about it.

KQ: Yes.

AR: And that’s what made me want that. I wanted to be like them and I wanted to do like they do.

KQ: Did you know that from a young age? Did you have that realization then?

AR: No. I was a dancer and piano playing blob in my happiness when I was a child. I was really inside of music. I didn’t have a sense of visuality. I loved language, though. I remember writing with a marker on the back of my headboard before I had been taught to write. I just wanted to do it and I was attracted to that. But the feeling of, “I have to do this, I have to have this,” didn’t come until adolescence. I was very superstitious and felt like I could only have one gift. I quit dancing because I started to feel like, “I don’t think I love this.” It’s like the way you can feel it in the early times with lovers, where for the first time you experience what it’s like when you’re not super 100% in love. That feeling. When the tone dips a little bit. I got nervous with that ambiguity. It’s too bad because there’s no law. It’s a completely patriarchal, idiotic idea that I couldn’t do dance and write.

KQ: But it’s really real and we’re told that so much.

AR: I was superstitious about passion. And then the shit hit the fan in my family. It caught on fire. It had always been very shaky, but my mother was first evicted and first became homeless when I was 18. I was sort of like a teen mom. I was like a young mom.

KQ: It really fucks with you when you have to be the adult to the person who hasn’t even finished raising you. And maybe they didn’t do a great job on the care part in the first place, and then you have to turn around and give the care.

AR: It’s very confusing. That experience, though, it did something to me. I was always attracted to language. I was attracted to beauty. You know what I mean? I wasn’t about to sign my name in blood and go, but something happened to me through that experience and I was pushed very, very deeply. I always loved reading and I always loved imagination, but I was pushed so hard into it. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s like if somebody came up to me and just pushed me.

KQ: I understand that completely. I feel like I pushed myself into poetry. I had not put that limitation on myself, but my first love was art. I thought I wanted to do fashion design. I was trying to do that, to go to school for it, but neither of my parents went to college and they didn’t know how to help me. Counselors were useless, so I was just going to be a teacher. I had a scholarship to an HBCU in Georgia but then my financial aid got messed up, and I tried to go to community college and then there were more family dramas. We had to move from L.A. to Michigan because I had a sister who was on drugs, and she had five children. So I was also eighteen when that happened. And in Michigan I was working two jobs and trying to go to school.

Then I got recruited into the Navy. I took the ASVAB test and I scored a 96 out of 99, so I got the extra money for college, so I signed up. I was like, “I’m getting money for college. I’m going to see the world. See ya!” [Laughter]. So poetry came to me. I always had a little notebook. I had a notebook when I was on the ship. I still have it somewhere. A little blue and gold notebook with my beginning scribblings. I don’t even want to call them that. They were intense. I really had a sense of feeling even if they weren’t publishable. I’m glad I still have that little thing. And when my son was just a few months old I took a poetry class and I became obsessed. My mom watched my son when he took a nap and I would walk the block to Barnes and Noble and I would just start with “A.” I read everything in Barnes and Noble. When I finished in the Barnes and Noble, I went to the library. If I finished one library, I went to the next library. I pushed myself into it wholeheartedly, all the way. I had found a place where I could articulate how I was feeling. I didn’t grow up that way. And certainly not in the military, where—who gives a fuck about your feelings? So as a mother, I found it imperative to be clear about how I was feeling and what I wanted. Like, what my intentions were.

AR: That’s so magnificent. You literally mothered your way into poetry.

KQ: Yes. Poetry and motherhood happened at the same time.

AR: That’s so beautiful. I love that because it also confirms my feeling that it was a tone [Laughter].

KQ: Yes! I was at this retreat once, and this dude was trying to say that a woman can’t be a great writer if she has children [Laughter]. I just started naming people. I was like, “Well, Toni Morrison has two children.” Lucille Clifton, Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde. I just kept naming people. He was wrong, but that’s still a belief.

AR: There’s a calcification. It’s hard for me to even comprehend some of this stuff. It’s just dry shit. There’s some Zen poem that says like, “Zen is like a dried turd.” Basically, calcified ideas of what art can be are old and dry.

KQ: And the ideas of who can fucking make it.

AR: It’s also like it’s a different tone. You don’t play every song in the same key. It’s ludicrous. But there’s something very weird and hardened that people have. I think one of the reasons people find resilience in this book— and I do, too, but I’ll speak of it better— is that coming into being is what it is about and what it is here for. There’s incredible diagnostic lucidity. There’s genuinely heartbreaking accuracy. There’s laughter, there’s humor, there’s recognition, there’s the situation, there’s great compression of time and space. But it’s also like, “Come and live.” Let’s find a way to live. That feels maternal in a wonderful way. It’s like, well this tune is in D, and that one is in B flat.

KQ: The maternal is also intellectual.

AR: Yes.

KQ: It also has the power to be accessible, valuable, useful, present, and undeniable.

AR: There’s all the pain and the anguish, but you’re not making a fetish or a martyrdom statue.

KQ: Yes. No spectacle.

AR: It’s in motion. I feel that we don’t yet have good language to talk about this kind of art. I think that that’s a compliment.

KQ: Thank you. I think it is, too, and I think that’s why more folks who may not have been academy-trained—or polluted, but I shouldn’t say that—need to write about how to read. Need to write poetry.

AR: That’s beautiful.

KQ: My dissertation advisor, Dr. Tayana Hardin, gave me Black Women Writers at Work, edited by Claudia Tate. That book changed my mind about what poetics essays can look like. Just women, particularly Black women, not shying away from talking about life alongside their writing. Making it practical. It’s not just theoretical, lofty, objective fucking horseshit. Writing is how we live, how we get through life. This is how we think, how we read, how we talk about living—and reading and thinking shapes culture. And if we’re going to influence that culture, then more folks like us need to be shaping the conversation. I was definitely thinking about that when I was writing the book as an undercurrent of all that feeling.

AR: I think that’s incredible. I also think more poetics will emerge by people who are not academy polluted because in five years there’s going to be no academy. Sorry. There’s a side to scholarship and to the care and the guardianship of neglected, untrendy things that I have a great love for. I like the back corner of the library. I like books that no one has taken out in 60 years. I’m not rejoicing at all at that going up in flames or at the good going out with the bad. But there’s so much corruption and agglutination and calcification in the creativity in people. You can have a passion for very weird ideas but I think something that’s interesting—if I can return to the earlier jalopy of resilience—is that art should be practical. I’m not saying that it should serve some purpose, that it should be comprehensible, or that everything we do has to make some kind of sense or be able to serve a cause. But it does need to fit into our lives. We can’t live without it.

KQ: We can benefit greatly from having poetry be part of our lives and being able to talk about it without fear or trying to impress people. That whole veneer of pretense is what I can’t stand.

AR: I like when you said, “No spectacle.” I feel like the more we listen to music, the [more?] we play it. The more we’re dumbed down by a monolith, the more we’re divorced from our own capacity to find creative ways to be with God or be good or just love or be not insane. Somehow, in order to do this practice, it has to fit into your real life. The modes of practice that require a man to have no children or to not raise his children and let the women deal with it, or that require that man to be served by an entire oppressive apparatus in order for him to produce the works of his genius don’t make any practical sense. It’s a bad use of resources. I feel like Shakespeare had no money and the babies were crying and the bills were due and the house was a mess. Like, the real work that we still live on was written under absurdly dire circumstances by people who were fairly desperate. Toni Morrison was raising two kids and working a very high powered job. She fit it into her life and that’s why it still lives.

KQ: And she had friends who would come over and just bring groceries. And be like, “I’m watching the kids, go write.”

AR: Can you imagine? When I’m working, I get so weirdly solitary and superstitious. It’s very hard for me to turn off that mode. But, at the same time, I do ten thousand million things and I know how to live in that. It’s the substance of real life that makes our art.

KQ: I definitely feel that. I have always been a writer and a mom at the same time.

AR: You literally have.

KQ: Sometimes going through the worst possible situations and not being able to write because of it lets the work sit in my head. But I think that having been forced to find a way to keep a person alive and make a book at the same time—because I needed that in order to stay alive—gave me a practical sensibility when it comes to reading and making art. I am writing poetry, and trying to make it interesting to people who are not academic. Otherwise, what are you doing? I don’t need ten dollar words. I don’t need to write teleology or teleological eighty thousand times [Laughter]. I really don’t. Why can’t practicality be smart?

AR: It is smart. That is the real smart.

KQ: You have to do things that are relevant to the world, because otherwise what kind of world are we going to get? We’re going to get the world that we got now. This bullshit.

AR: We get this. We get precisely this.

KQ: We have to actively shape cultural thought. And I know that if what I’m saying goes wrong, we’re going to be in trouble because we’re trying to shape how people think. And who are we to do that? But if we don’t, then it gets left to the wrong people.

AR: For me, it starts with me. I’m trying to shape how I think.

KQ: Yes.

AR: I’m conscious that I don’t want to drink bilge and have sex with a Big Mac all day. I can’t do that. So I have to shape how I think. First of all, this has to do that for me, or else I’m just another wretch on the side of the road that you have to scoop up with a forklift. I don’t think I’m far from those people.

KQ: Because we’re not.

AR: I was thinking a lot about the financial pressure that people are under. I lived in that state for 10 years. I was very financially precarious until this prize, frankly. And I’m a very hard working person. I work very hard.

KQ: All the poor people I know work harder than all the middle class and upper class people I know.

AR: I always had a million jobs and a million places to be and a million deadlines and I liked working all the time. I would joke that it was unbecoming for a poet to be so busy.

KQ: You have to have space around what’s happening in your brain in order to be able to translate it to the page.

AR: You do. But I do think that there’s something about when you said about letting it sit in your head while shit was going on when you didn’t have the luxury of space and time. There’s a lot to be said for building up pressure and desire inside your own body. People think they should be some type of machine when they write, but when you build up that pressure, it helps you with a certain clarity.

KQ: I agree.

AR: It’s good to do it for a long time. You can build up the longing to come back to writing the same way you can build up longing to see a person. To have a certain feeling. That longing is actually part of the work.

KQ: Yes, it is. You’re constructing the circumstances that you’re longing for.

AR: Boom. I’m sure there are a million things that we could discuss, but I’m mindful that it’s been over an hour.

KQ: Holy smokes. Yes, we just were just chit chatting.

AR: Are there things that you want us to discuss? I don’t think that was chit chat. I thought that was very important.

KQ: It was. Our chit chat is important [Laughter]. That’s what I want to say, too, that women’s talk across time has been dismissed, silenced, and characterized as frivolous, but that is where I learned how to live. Practical advice for living. Why can’t that also be valued at the same level? That kind of knowledge is not valued at the same level as academic knowledge. Speaking as a person who’s in the academy [Laughter]. And I don’t want to call it subversive, but I am interested in how to make the academy more accurate in reflecting how things actually work in life. That means being flexible, being caring, and being a person while still maintaining professional behavior. You don’t get personal with your students in the same way you do with a friend because you’re teaching them. But if they’re going through some shit and they need a day to turn in their assignment, give them a fucking day and don’t take any points off. That kind of shit.

AR: It’s always the women or the queer poetry teacher who will be the therapist, the parent, the friend. When you’re visible, it’s very peculiar to do that while being seen and while showing up. You keep showing up in your own career, and yet you’re sort of a fugitive at the same time. That is a quality of being a woman artist in this time. It’s very, very strange. And you’re carrying trauma.

KQ: With male artists, there’s been this glamorization or valorization of their suffering or their itinerance. Women are not necessarily afforded that. I noticed something when I was in Europe last summer. I spent so much glorious time in France and I went to the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen. There was an exhibition on Braque, Miró, Calder and Nelson. There was this image of the men in this Bugatti on the beach and then the wives were taking care of the children. There was a studio picture of them doing their work and the wives supporting that work with their labor. I just got so angry. I just want to do my work. Why does my work have to be defined through whether or not I’m a mom or married or itinerant? Why can’t I just have a focus on the work, and/or why does my gender dictate how the work is received or appreciated? I find that gender is more a determinant of how much work I get to do, and I keep imagining a world in which that reality transforms into something more generous, lucid, natural, accessible, and—dare I say it—joyful.

AR: That was beautiful, thank you for hanging out with me.

KQ: Thank you, Ariana. I really appreciate you.

AR: Thank you. I appreciate you so dearly. Until next time. I hope there will be a next time. In real life!

KQ: There will, dammit! Not in a rectangle [Laughter]. I will see you in non-corona air.

AR: Clean air.